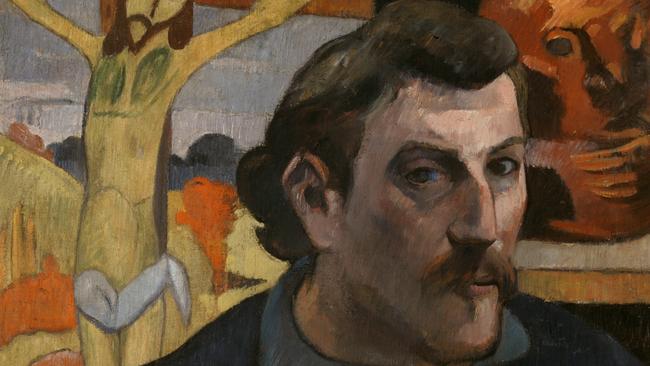

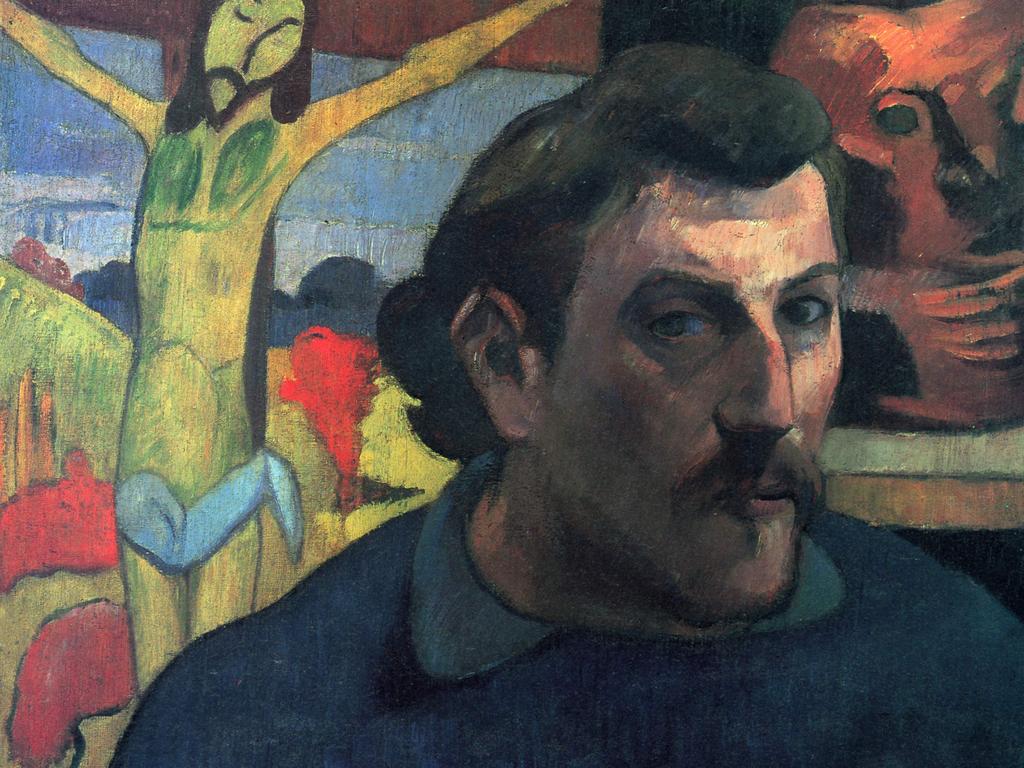

Will the real Paul Gauguin ever be revealed?

For all his personal and creative faults, artist Paul Gauguin remains a focus of attention.

Strangely, a number of books about French painter Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) begin at the end of the story. Biographer David Sweetman, for example, takes his readers first to the deathbed in Atuona in French Polynesia. As if at the outset they must be reminded of what they probably know already: that the artist died on an island about as far from the centres of the metropolitan art world as it was possible to go; and that his afflictions included advanced syphilis, the upshot of a life of profligate, if not predatory, infidelity.

The writer who inaugurated this trend was, however, a Gauguin advocate, Maurice Malingue, the journalist and film critic who edited, rather badly, Gauguin’s letters to his wife and friends. He refers to Gauguin swooning, losing consciousness and being found lifeless. The “faithful old Marquesan” Tioka is said to have thrown himself on the artist’s body, and cried out “Gauguin is dead, we are lost”. Tioka was no doubt genuinely saddened by the event. He had lived near Gauguin, who hosted him regularly and gave him, a few months before he died, part of his land, after Tioka’s house was washed away during a catastrophic flood. Yet the suggestion that he declared collective anguish in the terms described is ludicrous. Malingue was drawing on a letter of one of Gauguin’s friends, Protestant pastor Paul Vernier, and in fact, as Vernier recorded what Tioka actually said, it becomes clear the case was one of a simple mistranslation; the local idiom meant something like “he’s had it”, or “it’s over for him”.

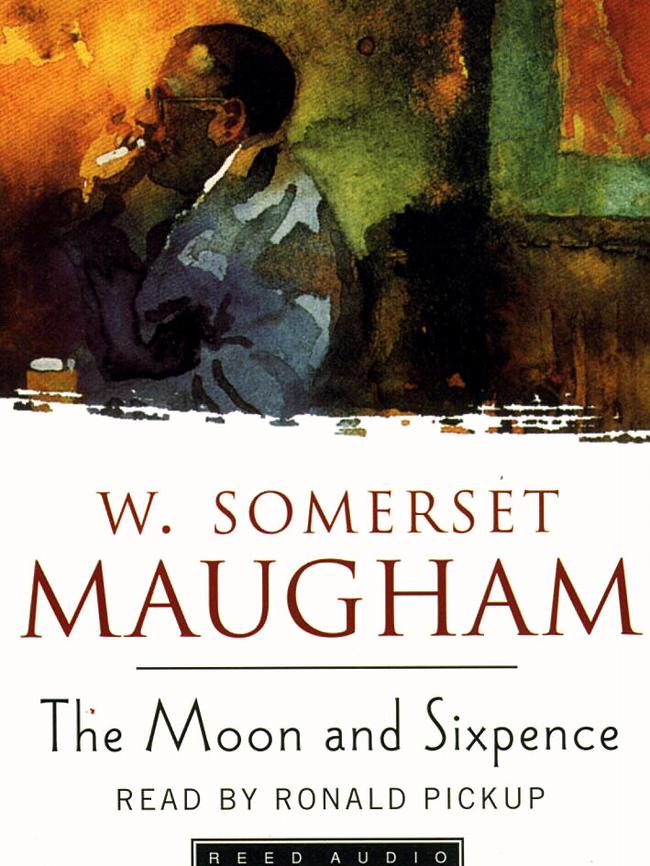

W. Somerset Maugham, one of the most prolific and prominent figures of English writing and theatre through the first half of the 20th century, spent his childhood in France and returned to Paris for a year at the age of 30, just after Gauguin’s death in 1904. Among those Maugham mixed with, Gauguin was a big figure; what he heard of the painter fascinated him; he talked at length with Irish painter Roderic O’Conor among others, and gathered material towards a book. But the project had a long germination. Maugham worked in intelligence during World War I, went to Samoa in 1916, and visited Tahiti briefly afterwards. There he met people who knew the artist, he found his house at Puna’auia, and was able to buy a painting on glass, part of a door Gauguin had left there. In 1919, he published The Moon and Sixpence; the title referred to a character who strained to reach the heavenly body, while failing to notice a coin on the ground in front of him.

The novel, which was immediately successful, conveyed through disconnected episodes the story of Charles Strickland, a London financier who abruptly abandons his wife and children after a long marriage and travels to Paris to dedicate himself to painting. He suffers near destitution, takes up with the wife of one of his few friends, abandons her, moves to Marseille, and eventually takes a boat to Tahiti. There, he finds Ata, a local woman, and settles far from town, painting and living with her and their child among locals; “He had gone native with a vengeance.”

Only latterly does the narrator, a writer who detests Strickland for his callous selfishness, encounter some paintings after the artist’s death, and belatedly grasps their uncanny power. “They were extravagantly luxurious. They were heavy with tropical odours. They seemed to possess a sombre passion of their own … yet a fearful attraction was in them, and, like the fruit on the Tree of Knowledge, of Good and Evil, they were terrible with the possibilities of the Unknown.”

Maugham is burdened with the reputation of being a truly excellent, second-rate writer. Which maybe explains why his rendering of Gauguin’s story was so simplified. Whereas Gauguin and his wife, Mette, in fact remained in close contact for over a decade after their separation, Strickland abandons his family abruptly, expressing total indifference as to their future, and refuses all further contact. As a character, he moreover brutally insults those around him, seduces the wife of kindly fellow painter Dirk Stroeve only because he wants to paint her, and otherwise is self-absorbed and aggressive. (Stroeve appears to be loosely based on Dutch painter Meyer de Haan, but Gauguin never broke up any marriage of de Haan’s, nor that of any of his various other artist-companions.)

Maugham did not attempt to represent or narrate the long and ambivalent afterlife of the Gauguin marriage; nor did he try seriously to tackle the charmless character who was nevertheless fondly regarded and considered a good friend by some people, and more fascinating than simply brusque by others.

The novel concludes with a kind of watered-down version of the end of Heart of Darkness. In Joseph Conrad’s great novella, Marlow visits the widow of Kurtz, desperately attached to the memory of her husband, and lies to her – the last words he uttered, he tells her were “your name”. (They were in fact the famous expression of revulsion from the maelstrom of colonial violence: “The horror! The horror!”) Maugham has his character similarly visit Strickland’s widow, to recount what he knows of the painter’s life in Tahiti and fairly sordid death. He thinks “it unnecessary to say anything of Ata and her boy”.

The Moon and Sixpence has been widely translated, adapted as a stage play, an opera, a film and for television (starring Laurence Olivier), and remains available in many languages today. More than the early French biographies and memoirs, notably including that of renowned writer, traveller and polymath Victor Segalen, the book gave global currency to a woefully crude version of the Gauguin myth, the anguished genius of mysterious imagination, the truculent personality who distances himself “with a vengeance” from civilisation and society.

Many dimensions of the actual life and work were obscured by Maugham’s image of the artist in his shabby paradise, indifferent to the world he has left. In fact, Gauguin engaged insistently with artists, friends, critics, dealers and prospective publishers back in Paris and elsewhere in Europe, to whom he sent letters, sketches, manuscripts, paintings and other works. Even his very last letters are largely concerned with upcoming and potential sales, references to his work in the press, and other art world matters. In one sense, Gauguin permanently removed himself; in another, through those communications and artefacts, he never left. The Moon and Sixpence was overtly a fiction, but has contributed disproportionately to the public image of Gauguin, the cliche of the flawed genius that endures in accentuated terms today.

Responses to Gauguin’s work were divided during his lifetime, and those who disapproved of his art did not belong only to a conservative establishment, but included political and cultural radicals. He has since become one of the most popular of all modern artists, but also been regarded with deep ambivalence, and is now censured, seen as a sexual predator in life and a colonialist in his art, guilty on multiple counts of cultural appropriation.

Hence, there is something of a standoff between a mainstream celebration of Gauguin, viewed for all his faults as a heroic adventurer committed to cross-cultural discovery, and in the opposed camp a critical dissection of reprehensible relationships and voyeuristic paintings of fantasised, misrepresented places and cultures.

There are, of course, many nuances to the views of scholars, curators, artists and the descendants of those Gauguin depicted, in Polynesia and elsewhere. And major museums around the world, well aware a Gauguin blockbuster will sell tickets as almost no other show can, try increasingly to have it both ways, vaunting the art, while inviting debate.

Over the past 40 years, I have walked around Gauguin exhibitions, fascinated but also frustrated. Over the same decades, I’ve been fortunate to have had chances to travel in Oceania, work and write around art, culture, history and empire in the region, and listen to Islanders from many Pacific nations and territories.

This book tries to offer another way of seeing Gauguin, beyond the standoff I have cited.

No reader of Gauguin’s Noa Noa, ostensibly a travel memoir, can doubt that as a writer, Gauguin was a retailer of stereotypes of the exotic. It has long been recognised that that book and other writings are unreliable, yet there is a peculiar sense in which both Gauguin’s advocates and detractors remain captive to them, and seemingly never quite grasped that in his personal letters as well as in texts he hoped to publish, the artist misrepresented not only Oceania, but also his own work.

“Gauguin’s mastery of the figure depicted in evermore fantastical, decorative settings enabled him to create compositions permeated with mystery and magic.” That is a received view; I quote a Christie’s auction catalogue entry for a painting that then sold for $105m.

Gauguin’s painting, sculpture and printmaking indeed do feature enigmatic symbolism, but the most arresting feature of the oeuvre is its sheer eclecticism. From the Pacific as well as elsewhere, many works contradict the familiar characterisation of the artist of exotic myth.

Gauguin’s works – if they are given the chance – reveal a Tahiti that was both mythic and modern, part of a colonial world and a realm of Polynesian culture, that sustained ancestral values still deeply salient to people’s lives and thoughts, even as those values were enacted in new ways, transformed over more than a century of European contact.

There is so much more to Gauguin’s art than the tired literary imagery of an alluring, mysterious paradise. As you begin looking at the signs of place and identity in his paintings, you enter into a world that you could not have anticipated.

This book is interested in rescuing the art from the artist, and from the myths he invented around the meanings and ambition of his work, that were amplified by acolytes and advocates, and that retain prominence even among detractors.

My goal is (not) a new vindication of Gauguin. Understanding his work in enlarged terms, and recognising that he did a sort of justice to, and even rendered monumental, the lives of then-modern Polynesians, makes both his successes and failures more thought-provoking. But it is not to deny or qualify the woefully numerous respects in which the painter was a difficult person.

There is no doubt he was deeply narcissistic, hence self-absorbed and inattentive to others, as well as arrogant, brusque and often socially inept. There is so much evidence for such behaviour that it comes as a surprise that some friends, including women, considered him generous, dependable and even “very nice”, as one of his Breton models put it.

Nor is it to suggest that Gauguin was not a colonist; the label was one he at times embraced himself. And nor finally would it deny that his art involved appropriation. The issue rather is that his relentless borrowing, or taking, had and has ambiguous effects. Again, once you begin to take apart and make sense of what he seems to do, the rich complexities of the work appear unending: the journey is more circuitous than you ever expected, but undoubtedly more rewarding.

Edited extract from Gauguin and Polynesia by Nicholas Thomas, Head of Zeus, $71.99. Gauguin’s World, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, until October 7.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout