Dumbing down or tech savvy: Why many music graduates can’t read music

In a trend one critic calls “Orwellian”, many music graduates today cannot read a score. Rosemary Neill reports on a trend that is sharply dividing the experts.

Student composer Dante Clavijo says he is “constantly asked’’ what kind of digital device or music software he uses to create his works.

The Australian National University student, who has already had an orchestral piece performed by Canberra’s National Capital Orchestra, inevitably replies: “I still use pen and paper.’’

The misconception he relies on technology such as digital audio workstations to compose his music, does not surprise Clavijo.

He says that because of advances in software programs, “it is now incredibly easy to make your own music. The whole idea of the garage composer is incredibly true nowadays. You can feasibly write a film score in your bedroom - and you do not need to read music to do it.’’

For his honours project, Clavijo is composing music by hand, then using a digital workstation to alter the way the sound is heard. Despite fusing the old and the new, he regards the ability to read sheet music as “incredibly important’’.

Songwriters and composers, he says, “absolutely benefit from knowing notation; it’s just a logical way to organise musical thought’’.

It may seem strange that a talented university music student is putting the case for learning music notation – those apparently familiar, graphic symbols on five-line staves that have guided composers and musicians for hundreds of years. After all, many, if not most, readers would assume that mastery of notation would underpin every tertiary music degree.

Yet Peter Tregear, a former head of the ANU’s school of music, points out that these days, students can graduate with music degrees without being able to read music, particularly if they are studying popular music and music technology subjects or degrees, and he is scathing about this trend.

“I find it concerning,’’ says Tregear, who obtained a PhD in musicology from Cambridge University and has worked at Cambridge, Melbourne and Monash universities. “It’s a misunderstanding of what universities are there to do. We’re meant to be expanding minds and opening horizons. … If you no longer teach musical notation, you effectively wipe out not just a good deal of recent Australian music history, but a large swathe of music history full-stop.’’

Tregear presided over the ANU’s music school from 2012 to 2015 and waged a battle to keep several notation-centred subjects in the music degree. He lost.

He attributes the decoupling of music education and traditional notation to the march of new technologies and - more controversially - to a push to “decolonise” the music curriculum, because the classical canon was largely created by “dead white men’’.

The outspoken academic, who has also won a Green Room Award for conducting, tells Review: “There has been, I think, a false or at least a very dubious conflation of arguments around the fact that western music notation is western music notation, and the idea that we shouldn’t favour it for that reason.

“To borrow an Orwellian phrase, ignorance is now a strength – it is considered that we’re actually better off not to teach this, which I find an extraordinary view for any higher education institution to take.’’

In contrast, most European countries still comprehensively studied their own music histories. Still, even in Europe, there was a push at some conservatoriums and universities to “decolonise” the curriculum.

“There is a move away from musical notation as being central to a music education as a kind of exculpation for western historical wrongs,” he says.

Tregear argues that if a music student is incapable of engaging with music that was “increasingly written down’’ over the course of 1000 years, “a whole wealth of the global musical past is effectively closed to you”.

But Barry Conyngham, a composer and music professor at the University of Melbourne - whose Conservatorium bills itself as the nation’s most prestigious music school in Australia – suggests that this approach to music education is outdated.

Professor Conyngham says judging a music program on whether its students have mastered notation “really is an absurd context”. “To focus on someone’s definition of reading music is a little bit old-fashioned, frankly,’’ he says.

He says Melbourne University’s music students – whether they can read sheet music or not – are “very musically capable of conveying musical performances and thoughts’’, and that the university prepares its music students for a wide range of vocations, from classical music performance to music therapy and film composition.

This broadbrush approach is clearly popular with students: enrolments have soared by two thirds at Melbourne’s music and fine arts school since 2010, and staff and students moved into a state-of-the-art $109 million building last year.

Asked if music students could graduate from the university unable to read music, the professor replies: “Depends on what course, to be fair. It (also) depends on what you mean by reading music. We have an improvised music course … I would imagine by normal lay terms, they would read music. Whether they read music in the same way as our classical musicians read music, is debatable.’’

Matthew Hindson, a composer and deputy dean at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, says all students at the Con must study music theory and notation.

However, given how The Beatles famously got by without a command of music theory, he asks whether, within the contemporary music field: “Is it going to be a deal breaker if you don’t know what a Neapolitan six-chord is?’’

In 2018, Paul McCartney shocked many of his fans when he confirmed in a television interview that he could not read or write music the traditional way.

“I don’t see music as dots on a page. It’s something in my head that goes on,” the-then 76-year-old said, adding he was embarrassed he hadn’t learned music theory.

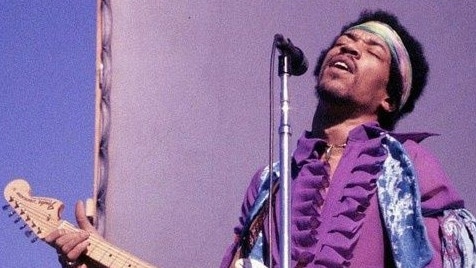

That McCartney and other songwriting greats – among them Eric Clapton, Michael Jackson and Jimi Hendrix - reached the pinnacle of their profession without being able to decipher “dots on a page’’, underlines, for some experts, the primary importance of auditory learning – learning to create and play music by ear.

Writer Tom Barnes has argued on the Mic music website that legends like McCartney were, in fact, trained in music - “most of them by listening and working to recreate the sounds they heard’’.

Barnes says “many highly-respected music educators have advocated for such methods … claiming that learning music as a series of symbols only distracts students from what is really important and powerful about music: sound”.

Clavijo is familiar with the story of The Beatles’ lack of music-reading nous. But he points out the fab four “were not alone in the creative space’’. Take their song, Eleanor Rigby, about a woman who lives and dies alone: While the song-writing was “fantastic, it wouldn’t be what it is without George Martin’s incredible, double string quartet arrangement on it”.

Says Clavijo: “George Martin could read music and he did have formal institutional training, which helped refine a lot of pieces that The Beatles did.’’

The young composer also says the subtleties of a Mozart score are easier to pick up on paper than on a computer-generated score, and that standard music notation is an international language shared by composers from many cultural backgrounds. He also finds it more convenient to commit his musical thoughts to paper than to use software programs.

Nonetheless, music-making software has become so advanced, programs such as ScoreCloud - developed by a fiddle-playing Swedish music professor – allow users to sing, hum or play a tune into the program and retrieve an instant digital score.

The phone app version allows users who can’t play an instrument or read music to record themselves singing, and their trilling will be reproduced as virtual sheet music. App co-inventor, Swedish computer engineer Sven Emtell, has said he wants to “revolutionise the music industry’’ by allowing anyone to become a composer. Is such technology a game changer for aspiring composers and songwriters, or an excuse to dumb down? Today, Griffith University and the University of Adelaide offer bachelor’s degrees in popular music, while the University of Queensland offers a major in popular music and technology.

Monash University, like many other tertiary institutions, gears its music courses to different types of students: Applicants for its music technology course undergo auditions in which they perform two compositions “created with music notation software, or by hand’’, while classical music applicants may be asked to sight read.

John Encarnacao, a lecturer at Western Sydney University, says it is “desirable’’ that graduates can read music, as this “acknowledges career paths that go beyond the stereotypical ‘I’m going to be a rock star or a dance music producer’ ’’.

However, if a degree focuses on sound engineering or studio recording and mixing “then yes, it’s conceivable it could be quite valid to have a music degree that doesn’t engage with notation”.

The music lecturer and guitarist who has written a book on punk aesthetics, adds: “I wouldn’t categorically say you shouldn’t have a bachelor’s degree in music if you can’t read music. I think it’s highly desirable that you have the facility of notation, but I wouldn’t be so absolutist.’’

He reveals that at WSU, “to a degree, students get to choose the extent to which they pursue parts of the course that have to do with notation’’. However, some of the university’s majors such as composition embed the skill and WSU alumnus Holly Harrison was “one of the most sought-after art music composers rising up through the ranks’’.

Interestingly, he finds “a fair proportion of students are reluctant to engage with music notation. They see it as something that is difficult – more difficult than it is in reality – and something they would rather not engage with. I just think they think technology’s going to do it all for them.’’

He says about half of WSU music graduates go into some form of teaching, and “need to be able to read music …That’s something that’s easily overlooked”.

On the other hand, music notation is often aligned with classical music, and he says the “stranglehold’’ such music had over tertiary music education “has been disintegrating since the 1980s and 90s. While it’s still a part of many bachelor’s courses in music, it’s no longer the be all and end all.’’

With his colleague Diana Blom, Encarnacao has co-authored the new book, Teaching and Evaluating Music Performance at University, which argues the traditional conservatory model of highly-specialised, one-on-one tuition has been largely superseded by group music teaching. He says “there are those who hold to that conservatory model and say, ‘No, no, no everything’s lost if I’m not training my precious piccolo players for a symphony orchestra.’ We have to accept that the music industry is not about training people to play in orchestras.’’

He argues for a middle path: as well as teaching traditional skills, music schools “need to engage equally with recording technology and the 21st century music industry’’.

Kim Cunio leads ANU’s once deeply troubled music school, and he advocates for the teaching of traditional music theory – and for decolonising music curriculums. He says classical musicians who lament falling standards are “not taking into account … that music schools need to decolonise”.

“We have an implicit assumption in multicultural Australia that the only dominant form of music is western classicism. Some of the greatest traditions in the world are completely oral.’’

Cunio is of Asian, Middle Eastern and Jewish heritage, and he says the music of Africa, Persia and India functions “quite well without a reliance on the reading of music. In many cultures, they don’t think that reading is that exciting.’’

The associate professor who keeps a yoga mat and grand piano in his office, is composing a piece about COVID-19, and he denies that decolonising the curriculum undermines traditional skills such as notation: “The greater risk for me is the potential for music schools to go down the popular music route.’’

When students say they can play their instruments “a bit’’ and that technology will do the rest, “that is a potential problem”, he says. He also says institutions offering popular music degrees that don’t require some knowledge of notation, is “potentially’’ a form of dumbing down, although “I’ve seen examples where it’s not’’.

More generally, he says music schools today “don’t get students to the same level we did 50 years ago (at reading music) but we teach them a whole lot of other stuff”.

Before Cunio took over as head of the music school in 2019, it had been mired in controversy and internal divisions for years, following radical 2012 funding and staff cuts, declining student numbers and claims of lowered academic standards as the school distanced itself from the traditional (and expensive) conservatory model of teaching.

Cunio says “it was strongly debated whether it should move away from elite classicism as the prime mode of delivery, and that was experimented on for a few years. When I became head of school, I ended the debates by saying, ‘We will make our standards as high as anywhere else’.”

Today, ANU music school applicants must demonstrate musical ability but don’t necessarily have to read music well, he says. However, once accepted, all music students attending the school must study some theory.

“(Today) I could safely say that every student of ours could read music, but they read music according to the music they make,’’ he says, choosing his words carefully.

While classical music students were the most advanced readers, jazz students were “pretty good at reading the melody line and the chord chart’’. Contemporary singers, he says, “would probably be the least skilled readers’’, while the university was revising its music technology major to ensure students could read the scores they edit.

Echoing Encarnacao, he says “the majority of people doing a music degree will (eventually) be teaching music’’ as “that’s where 70 or 80 per cent of the work is’’.

Moreover, research showed that “a good contemporary musician who goes through music school, their superpower is that they can read, write and arrange music’’.

Like her fellow student Clavijo, ANU PhD composition student Roya Safaei brings a mash-up of old disciplines and new approaches to her studies. She plays classical piano and also studies traditional Persian music, in which time-honored pieces are passed down through observation and listening.

“There is really no notation and improvisation is highly prized,’’ explains Safaei.

Still, she says that “at the university level, I see an ability to read music as an indispensable skill … notation has been central to the western tradition for a very long time.

“However, I also believe this should not be the sole focus of a music school, and that other skills such as improvisation should be equally encouraged.’’

Clavijo “totally agrees’’ with attempts to make music studies more inclusive, including reviving the work of neglected female classical composers.

Yet the student composer fears that if some music schools turn away from teaching musical notation because of objections to the male-dominated western canon, “you’re also getting rid of so much information, and that’s what I don’t necessarily subscribe to”.

“…To deny a lot of the musical knowledge we have gathered, or to outright reject it just because of the particular format in which it was (originally) presented, just seems ludicrous.’’