Australia uses 50,000 takeaway coffee cups every half-hour. Here is why plastic is no conspiracy

The pictures are awful, the numbers hard to grasp. And yet sceptics everywhere continue to pretend it is exaggerated

The magnitude of the statistics is hard to grasp. The pictures of strangled and starved wild animals are awful. And yet sceptics everywhere continue to pretend that the news is exaggerated or a conspiracy.

More than eight billion kilograms of plastic waste flows into the ocean every year, according to National Geographic, 40 per cent of which is plastic packaging that is used once and thrown away.

And that’s not just plastic shopping bags, though they continue to be a problem despite action taken by supermarkets and governments. The transition from plastic to cloth bags was easy enough but what to do about all the foodstuffs sold in plastic?

The plastic cartons for berries, the plastic vacuum packaging for animal protein that requires an electric saw to get through. And the packaging for frozen foodstuffs: what even is the alternative there that won’t go soggy?

Mindset is often more the challenge for dealing with problems than is the physical reality. Some of it is the usual assumption that what exists is what must be. Some of it is rampant individualism: the privileging of rights over responsibilities, of ease over duty, the self over the whole wild world.

Shoppers in the US use almost one plastic bag per resident per day, as opposed to people in Demark who use an average of four bags per year, according to a University of Wisconsin study.

In 2018, Britain’s Royal Statistical Society nominated as its “statistic of the year” the fact that only 9 per cent of all the plastic ever made was estimated to have been recycled.

We’re not just talking plastic packaging here. It is used in building and construction, fishing, textile manufacture, electrical products and much more. And when plastics do break down, which takes a very long time, they don’t dissolve into the environment but form microplastics, which are defined as fragments less than 5mm long by the US Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Microplastics have been found in the deepest parts of the oceans and within all animal organisms, including us.

Five years ago another National Geographic study estimated that “5.25 trillion pieces of plastic waste are in the ocean. Of that, 269,000 tons float on the surface, while some four billion plastic microfibres per square kilometre litter the deep sea”. Goodness knows what the figures are now.

This year, a Chinese study found microplastics everywhere imaginable. They concentrated on the three worst sources of intake for humans: table salt, water (especially from plastic bottles) and air (especially indoor air).

“When we inhale microplastics, the tiny particles can reach the lungs and digestive system. Nobody knows what this means for the human organism and our health, but as we are talking about a lifelong exposure, it’s a cause for concern,” one of the researchers, Genbo Xu, a professor of environmental toxicology, told physics.org in May. Animal studies show that microplastics can disturb both the metabolism and the intestines.

And as with pesticide pollution and poison, the higher up the predatory chain, the higher the bodily concentrations of microplastics, which is why nutritionists warn us to limit our consumption of apex ocean predators, quite apart from the threat of species extinction. In 2015 again, the US passed the Microbead-Free Waters Act, which banned the use of plastic microbeads in cosmetics and skincare products.

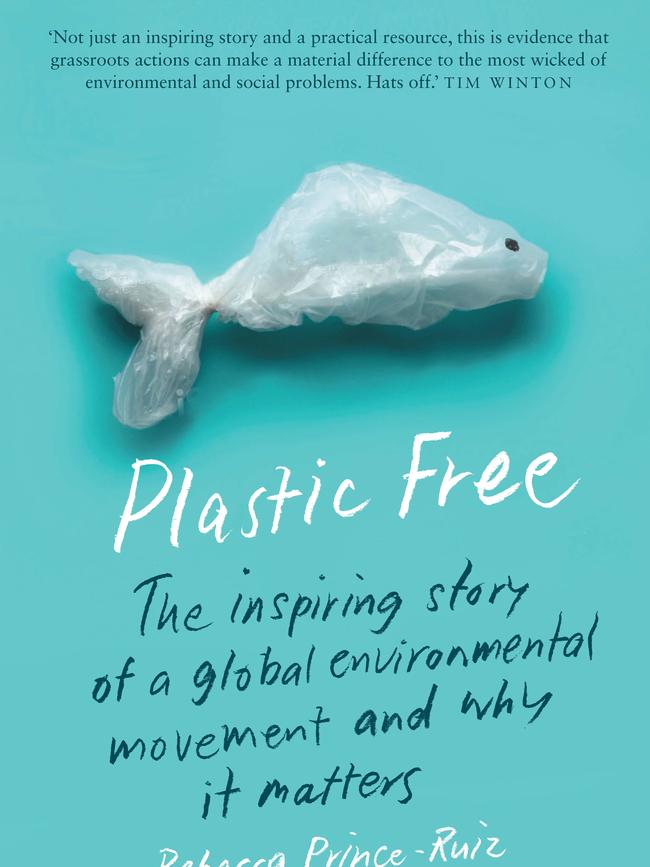

Plastic Free is a new book by Rebecca Prince-Ruiz, an Australian expert in environmental and waste management, sustainability and community engagement, written with journalist Joanna Atherfold Finn.

Prince-Ruiz launched “Plastic Free July” in 2011, roping in a few friends and colleagues. Today it counts a membership of 250 million people in 177 countries.

“For me, it was a trickle effect that had started with my earliest life experience having to leave my home due to human damage to our environment, and the environmental responsibility instilled in me by my parents,” she says in the introduction, explaining her interest. “Those experiences led me to study botany and geography; they inspired my curiosity and a sense of responsibility.”

The book tracks the growth of Plastic Free July and includes biographical insets about various individuals, community groups, NGOs and businesses that are now collaborating with the movement, from the Rottnest Island Authority in Western Australia to Lendlease at the Barangaroo South Precinct in Sydney to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums to Jackie Nunez, a landscaper, former river guide and founder of The Last Plastic Straw in California to journalist and sustainability blogger Vandana K in New Delhi to a slew of school and university student groups across the world.

The book is a little folksy, chatty rather than dense with scientific information, and that is the point, I presume: to reach out to ordinary people who are neither scientifically literate nor overtly political. It is full of motivating anecdotes, advice on the difficulties of trying to eliminate plastics in domestic life and how to organise locally and beyond. Funnily enough, the figures the author does drop seem to linger in the mind more than statistics delivered in bulk.

Plastic bags were only invented 50 years ago, for example, which made me wonder how our grandparents disposed of wet kitchen waste – and how I should. Disposable plastic bags are used, on average, for just 12 minutes before being thrown out to end up strangling a dolphin somewhere in the ocean. In the US, 500 million straws are discarded every day. And Australia alone uses 50,000 takeaway coffee cups every half-hour.

Cautionary tales and how-to- detail abound. I pride myself on making an effort to reduce my use of plastic, but this easy-to-read book places token observances into perspective and offers thousands of further small and large steps that can be taken.

Plastic Free: The Inspiring Story of a Global Environment Movement and Why it Matters

NewSouth, 262pp, $32.99

Miriam Cosic is a journalist and author.