When did universities become so soulless?

Campus was once a place for intimate, human gatherings and the exchange of brilliant ideas as is evident in this exhibition from the University of Sydney Union’s art collection.

The University of Sydney has a number of historically important museums and collections, which many readers will probably recall in their original locations around the campus, especially the Nicholson Museum, the oldest collection of antiquities in Australia, established in 1857 with the generous endowment of the university’s second chancellor (then known as provost), Sir Charles Nicholson (1808-1903), and subsequently enriched by further gifts from Nicholson and others, as well as from works acquired through participation in new archaeological digs.

The Nicholson Museum was originally housed in the middle of the first range of the Quadrangle to be built, the northeast wing,which was erected in the later 1850s and could once be seen from Hyde Park rising majestically on a low hill to the southwest, a symbol of learning overlooking the commercial city until it was blocked out by higher buildings at the south end of the park. The museum was later moved to larger rooms in the last wing of the Quad to be built, designed by Walter Liberty Vernon in the first decade of last century and finished by 1926. These quarters also eventually proved to be too small for the growing collections and yet the environment of the old Nicholson Museum was uniquely enchanting and inspiring.

Less well-known was the Macleay Museum of natural history, also eventually confined to rather cramped but picturesque rooms in the attic of the Macleay Building opposite the Quad. This museum too had its origins in the collections of another of Sydney’s leading intellectuals of the time, the Colonial Secretary Alexander Macleay (1767-1848), who also built the beautiful and fortunately surviving Elizabeth Bay House. Macleay was a distinguished entomologist, whose collection (expanded by his son and other members of his family) became one of the most important in the world. It was finally gifted to the University by Macleay’s nephew Sir William John Macleay, also a leading natural historian, after a suitably fireproof building had been erected (1887-88) for the highly flammable collection. Unfortunately this structure, originally entirely made of steel and masonry, was soon compromised when the university began to occupy parts of it for classrooms.

The University Art Collection, on the other hand, never had a proper home (although it held exhibitions in the War Memorial Bridge), perhaps because it lacked a scholarly basis and was not connected to any academic department. In fact even after the Power Institute of Fine Art was established in 1968 it does not seem to have had any direct role in or with the UniversityArt Collection; instead it began its own Power Collection of Contemporary Art, which eventually became the core of the Museum of Contemporary Art. As for the University Collection, it ended up with some 8000 works, some of which are of greater importance than much of the Power Collection, including a substantial bequest of paintings and drawings by Jeffrey Smart by Alan Renshawin 1976.

In 2005, all of these collections were amalgamated administratively into a body called Sydney University Museums and in 2015 it acquired a new name after wealthy Chinese businessman Chau Chak Wing donated $15m for the construction of a new building. The new University Museums building itself is a successful design; the potential brutality and blockishness of its exterior is mitigated by the old trees growing around it, and the interior has a sense of grandeur, spaciousness and clarity – in striking contrast, as I have observed before, in all respects with the mean, confused and ugly interior of the AGNSW’s recent extension.

In addition to the collections already mentioned, the University Museums now also house a smaller group of works which could easily by overlooked among the thousands of pieces in the Art Collection, but which are now the subject of an exhibition of their own: and that is the collection of the University Union, which once had its own exhibition spaces (first the Sir Hermann Black Gallery and then the Verge Gallery) but was transferred to the University Museums in 2019.

The history of the union goes back to 1874, when the original body was established as a debating club, on the model of the Oxford Union, founded in 1823 and still today the most famous debating society in the world. In 1907, Holme Building was constructed for the union. In 1914, a Women’s Union was founded and Manning House was built for the new body in 1917; finally in 1971, the two unions, whose activities had greatly expanded and diversified over the intervening decades, amalgamated and commissioned the new Wentworth Building on City Road.

The exhibition is interesting in itself for the quality of the work, but even more significant in the changes it reflects within the nature of the union and more broadly of university life itself, and the evolution of both from a more intimate and personal scale to the industrial impersonality and anonymity of modern campuses, where student facilities can feel as slick and generic as an airport, apart from occasional tatty little posters urging students to destroy capitalism or, as I saw at UTS some weeks ago, brightly-coloured monitors hinting that asking someone his preferred pronouns could be a promising pick-up line.

When the union was originally founded, it only had a couple of hundred members, including staff and alumni. For the first few years, until 1882, they were all men (the admission of women was approved in 1881). In 1902, 50 years after the admission of the first students in 1852, enrolment stood at 730.

In 1921 there were 3275; by 1975, after the abolition of fees by the Whitlam government, student numbers rose to 17,700. They then virtually doubled with the amalgamation of the former Colleges of Advanced Education in 1989, and today the University has an enrolment of almost 70,000. The student body has thus evolved from a small group in which everyone could know everyone else to a scale at which it is hard to feel any general sense of community, and in which most people you meet will be strangers.

This development is inevitably reflected in the kind of art that was purchased by the union and the circumstances in which it could play a part in student life. Early works were smaller and were suited to modest interior spaces as well as a quieter environment in which some at least could be expected to stop and enjoy a painting on the wall.

A glance at the dates of acquisition of various pictures in the exhibition suggests that there was a general continuity of culture up to around 1970 or so.

Thus among the earlier works in the collection, there is a small woodcut by Albrecht Duerer, Christ before Caiaphus (c. 1508), purchased in 1963; a Flemish painting by Mattheus van Helmont of an interior with a serving woman and an elaborate still life (c. 1650), gifted to the collection by H.B. Gritton in 1926; a handsome Italianate classical landscape by the Dutch classical master Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem was gifted by the same man in 1938, and indeed may have been a bequest, for Gritton died in November 1938; his death notice in The Sydney Morning Herald mentions that he was educated at Sydney Grammar School and Sydney University and that he was Deputy Master of the Royal Mint in Perth at the time of his death.

The union could make unconventional acquisitions too. In 1939, the Herald Exhibition of British and French Contemporary Art, supported by Sir Keith Murdoch, provoked considerable controversy and was severely criticised by some – J.S. MacDonald famously described many of the pictures as the work of “degenerates and perverts”. Nonetheless, the union paid £93 for Maurice de Vlaminck’s Paysage (after the storm), freshly painted in 1939. It is a strong and dramatic work for a painter not known for his subtlety.

The years between the wars seem to have been an active period for the collection, perhaps in part because compulsory fees (since 1917) from a growing but still manageable student body meant the union had more funds for acquisitions.

Pictures like Herbert Badham’s La Perouse holiday (c. 1936), Robert Campbell’s South Coast (c. 1937), and Norman Lloyd’s Musgrave Street Wharf (c. 1938) were all purchased in the years they were painted and thus presumably from the artist’s exhibitions — probably indeed from Macquarie Galleries, which was then the leading gallery in Sydney and one at which all three artists had shows.

In the 1960s there is what seems like another important period of collecting. On the one hand there are acquisitions of older pictures, as though to fill gaps in the historical narrative – for example a beach scene by Elioth Gruner from 1918, donated by the Women’s Union in 1960, or Arthur Streeton’s Corfe Castle (1909), purchased in 1965; but on the other hand there are also examples of contemporary art such as Richard Larter’s Pluto the playful pup (1967), once again no doubt bought from the exhibition in the same year. A number of other contemporary abstractions which have not aged particularly well were purchased in subsequent years: David Aspden (1970), John Peart and Louis James (1971), and Sandra Leveson (1972).

In 1972, the new Wentworth Building project was launched, in Brutalist style, and accordingly a number of very large hard-edge abstract paintings were acquired with a view to complementing the new architectural environment, so different from the proportionsand scale of the Edwardian Holme Building. Today these big abstract compositions by Col Jordan (1971, purchased 1972) and Barrie Goddard (1970, acquired 1980), which must have looked aesthetically exciting at the time, seem to evoke more than anything else the sterility of the architectural environment they were intended to animate. And these are not pictures that invite you to approach and look carefully at them; they are loud statements seen at a distance on a concrete wall.

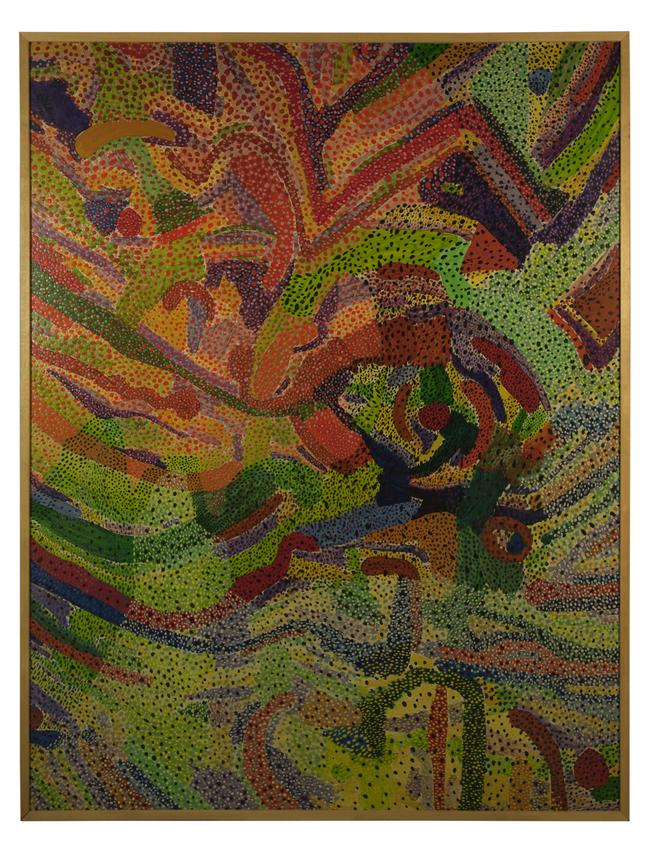

In the 1990s, collecting interest seems to have turned to Aboriginal art, and fortunately choices were generally judicious: the best of these pieces are bark paintings by John Mawurndjul (1997, purchased the same year), George Milpurrurru (1988, purchased 1989) and Thompson Yulidjirri (c. 1984, purchased 2008). These are indeed paintings that reward closer and more patient attention, like many of the earlier works and a number of fine drawings exhibited in cabinets in the middle of the gallery. But by this time the social environment of the university was already changing irreversibly.

The intimate, club-like conviviality and smaller, human spaces of only half a century earlier were gone; in the new university, lecturers and students were being inexorably reduced to service providers and customers respectively: the institution was becoming a factory for the production of qualifications, not a place of leisure, reflection and aesthetic enjoyment.

Union made: Art from the University of Sydney Union Collection, Chau Chak Wing Museum to March 16

Images: University of Sydney Union collection

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout