When art and Antarctica collide: exhibition reveals depth of meaning

Striking works by artists who took part in the Australian Antarctic Division’s residency program between 1987 and 2009

P

olar environments are not obviously inviting to artists. What is a painter, for example, to make of a place that has no treesor plants and therefore little or no colour? The landscape feels barren and inanimate, like a world before the appearanceof life itself. In some areas, there is not even land but only sheets of ice and floating icebergs: a monochrome world offrozen masses floating in an icy sea under leaden skies.

It is not surprising, then, to find that the artists included in this exhibition, all of whom had the opportunity to visitthe Antarctic as part of artist-in-residence programs offered through the Australian Antarctic Division between 1987 and 2009,are mostly printmakers. Media that is inherently based on ink and paper, on black and white – even if it has sometimes incorporatedcolour in various ways – is, on the face of it, better suited to such austere subject matter.

The Antarctic was the last continent to be discovered, although its existence had been postulated as part of the great TerraAustralis that ancient geographers conceived as necessary to balance the continental masses known in the northern hemisphere;even the name Antarctic was used in antiquity to refer to the pole opposite the northern or Arctic pole (the name itself comingfrom the constellation of the Great Bear, arktos in Greek). Early maps and globes, after the first sighting of the Australiancontinent in the early 17th century, often represent an amorphous land mass extending from Australia down to the polar regions – as for example in Andrea Sacchi’s ceiling fresco of Divina Sapienza (1629-33) in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome.

The introductory wall label in the exhibition in Hobart cites Edmund Halley as the first man to sketch tabular icebergs inthe Southern Ocean in 1700, and James Cook found “ice islands” when he sailed into the Antarctic Circle in 1772-73. Accordingto the absorbing and moving summary of the history of Antarctic exploration on the Royal Museums Greenwich website, Cook wasthe first modern navigator to have sailed into these waters, but did not find land.

The continent itself was first sighted in 1820, possibly by Fabian von Bellingshausen, a Russian explorer of German descent,or perhaps around the same time by British naval officer Edward Bransfield. A series of British expeditions followed duringthe 19th century, but it was not until the end of the century that land exploration began, when in 1899 a British expeditionled by the Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink became the first to spend a winter on the continent, and the first to use sledgesand dogs.

This was the beginning, as the Greenwich site points out, of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration in the years before andduring the Great War. Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen became the first man to reach the South Pole in December 1911, justover a month before Robert Falcon Scott, who died tragically with the other members of his team on the return journey, endingin March 1912. This was followed by Douglas Mawson’s expedition in 1912-14 and Ernest Shackleton’s trans-Antarctic expeditionin 1914-16, both epic feats of human endurance in the face of a monstrously inhospitable environment.

The image of an uninhabitable world fascinated romantic painters, epitomising the idea of the sublime, which also had itsroots in antiquity but had been defined for the modern age by Edmund Burke in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin ofOur Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). In essence, the concept of beauty refers to that which is harmonious, welcomingand conducive to health and happiness, while the sublime represents the very different aesthetic of things that are terrifying,vast, alien to man but exhilarating – like the ocean, great mountains or the infinite space of the heavens.

Such spectacles move us pleasurably when seen from a distance; one of the most familiar, if not overused examples being CasparDavid Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) in which a hiker (the proper meaning of the German wandern is to hike)has reached a mountain peak and is seen from behind gazing across an endless prospect of rocks and swirling fog.

In fact sublime mountain views had appeared in earlier landscapes from the Flemings to Claude Lorrain himself but were usuallyconfined to backgrounds; Friedrich, like Turner and others, brings us closer to the spectacle of the sublime and makes itthe principal subject of his painting.

But Friedrich also demonstrated explicitly how uninhabitable the sublime really was in one of his most remarkable compositions,and probably the most striking image of ice painted: The Sea of Ice (Das Eismeer, 1822-23), which has also been known by severalother titles, and represents a polar expedition ship being crushed like a child’s toy by the overwhelming power of pack icesheets.

The subject has always been associated with the North Pole, but it is curious to note that it was painted just a few yearsafter the first sighting of the continent of Antarctica.

This picture anticipates, perhaps without direct influence, a later sublime icescape mentioned earlier this year, Isaac WalterJenner’s Cape Chudleigh, Coast of Labrador (1893), but it was certainly the direct inspiration for another work discussedhere some months ago, Tacita Dean’s enormous chalk drawing The Wreck of Hope (2022), named for an alternative title of Friedrich’spainting Die Gescheiterte Hoffnung (Ruined Hope). It also inspired Paul Nash’s Totes Meer (Dead Sea, 1941), whose German titleis a direct tribute to Friedrich but also an ironic reference to the painting’s subject: a dump of wrecked German aircraftshot down during the Battle of Britain and gleaming in the cold moonlight.

The first two artists in the Hobart exhibition to visit Antarctica were Bea Maddock (1934-2016) and Jan Senbergs (1939-2004),who both, according to an exhibition label, “joined a resupply mission to Heard Island, Scullin Monolith, and the stationsLaw, Davis, Mawson and Mirny in the summer of 1987”. The experience, we are told and can easily believe, made a profound impressionon each of them, but it is interesting to see how very differently this is expressed in their respective works.

Maddock seeks to convey the emptiness of the environment, an impression that in her case was exacerbated by an unfortunateaccident: she badly fractured her knee on Heard Island before arriving on the continent, and her work Forty Pages From Antarctica(1988) is “based on the sketches she made from the ship’s cabin while waiting to be evacuated”. The sheets appear almost whitefrom a distance, with minimal use of etched lines to suggest the line of the coast and its ice sheets, with an enigmatic textblind embossed along the bottom of each page.

Senbergs’ etchings, in contrast, are extraordinarily full, animated and crowded with incident, for they evoke the human presencein Antarctica rather than the vastness of the desolate white continent. One of his works shows Maddock being lifted on tothe Icebird for evacuation. The artist watches this event from the point of view of one standing on the deck of the rescueship, while Maddock’s body, bound to a stretcher and warmly wrapped against the cold, is winched up from a small boat below.

Senbergs’ choice of lithography allows him to reproduce directly the graphic energy of his drawing, which fills the pictureplane from edge to edge, leaves few still spaces of quiet and tends to flatten the image into a tangle of graphic energy,an expressive correlative of the energy and dynamism – but also the crowding and detritus – that he sees around him.

Stephen Eastaugh (born 1960) has been to Antarctica three times and was the only artist to have spent a winter in Antarcticaduring an 11-month stay in 2009, undoubtedly a feat of endurance, especially around the winter solstice, which is the subjectof the work in the exhibition. The 30 panels of A Good Day Tonight (2009) record the period in which he lived without naturallight. The works are composed of irregular grids painted in shades of brown and black, occasionally alternating with whiteand sparingly animated by white threads that recall the patterns we see when our eyes are closed or in the dark. This is acase where a minimal yet never mechanical style is effective in expressing intense experience

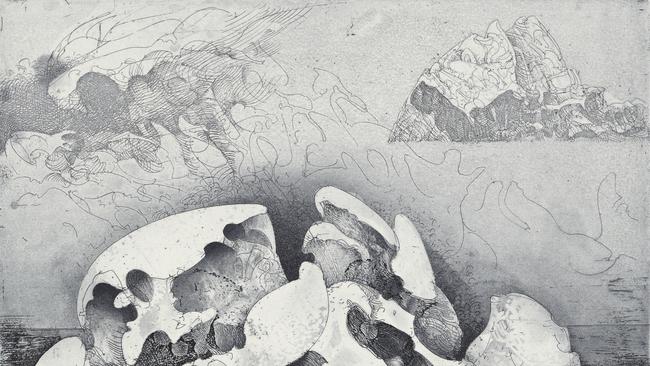

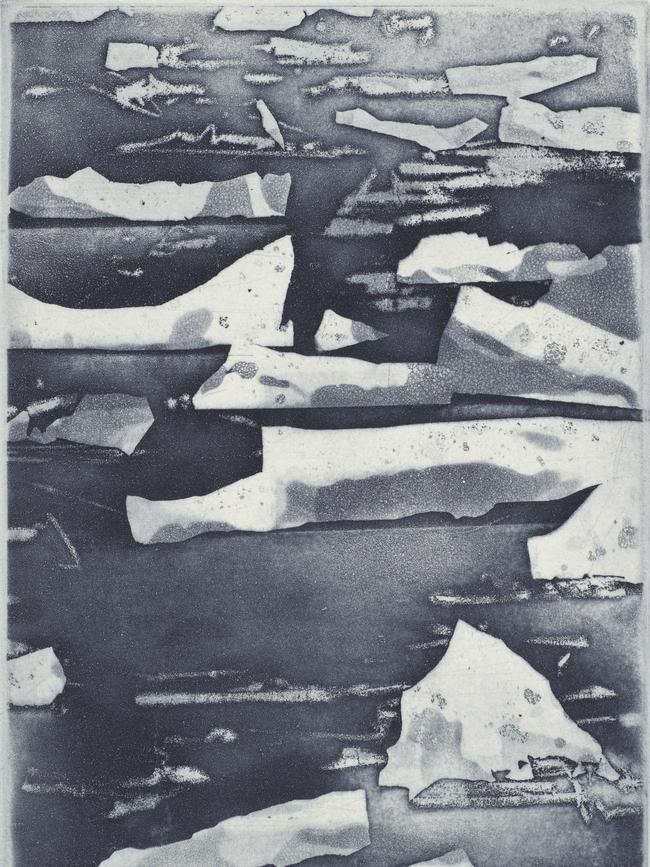

Perhaps the most interesting works in this exhibition, however, are by Joerg Schmeisser (1942-2012), a virtuoso printmakerand former head of department at the Canberra School of Art who has used many different approaches to etching – even photographicetching in a couple of works – as well as lithography in one case to capture the ineffable and alien character of the frozenenvironment. It is also no surprise to learn that Schmeisser was deeply influenced by Friedrich, whose Sea of Ice he firstsaw at the age of 10 in Hamburg.

Schmeisser sailed to Antarctica in 1998 on board the Aurora Australis on its annual resupply mission to Mawson and Davis stations,and works from this time and subsequent years were shown at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2003 under the title Breakingthe Ice.

What he is really trying to do, however, is to find fresh ways to represent a subject that is massive, sublime in scale andterrifying yet at the same time, as the frozen form of a liquid substance, almost immaterial compared with geological phenomena.As Schmeisser wrote, he wanted “to find different ways of holding and presenting the ice; something that showed the othernessof this place, compared with my previous themes: landscapes, monuments, figures and shells”.

One way he attempts this, as in Twister (2004), is by defining form negatively, making use of the specific aesthetic resourcesof etching: thus the lit surfaces of the iceberg are represented by almost white areas, while the hollows and shadows aredeeply and darkly etched.

In another image, Berg I (2002), the approach is slightly different, and the distinction between lit surfaces and shadowedhollows is attenuated. In Breaking the Ice (2003) he plays with the contrast between distinct edges and indistinct or indefinabletransition; in another series, including Moving Layers (2003), he seems to be using aquatint to produce a purely tonal imagewithout linear definition; while in Double Berg (2002), he employs a combination of aquatint and “foul biting”, as in manyof Fred Williams’ etchings.

But what is striking in all of these works is the way Schmeisser makes such intuitive use of his medium, in which forms arebitten into the copper plate by acid, as though sensing or feeling his way towards some analogy between this process and theway the seawater itself has carved glaciers and ice cliffs into their dramatic but ever-shifting forms.

Artists to Ice

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, to February 9 next year

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout