What’s wrong with this picture? Artist Johannes Leak’s portrait of Jewish leader Alex Ryvchin rejected for Archibald

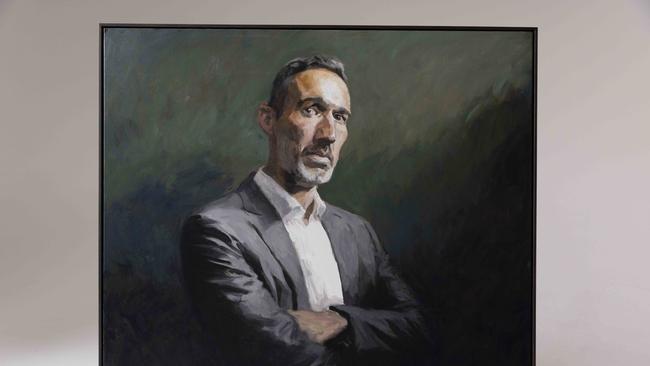

Johannes Leak knew the Archibald Prize trustees might reject his portrait of Jewish leader Alex Ryvchin, but painted him anyway, illuminating Ryvchin’s journey from Ukrainian refugee, born in the shadow of the Holocaust, to proud advocate for his people.

There’s a ray of light that drives Alex Ryvchin bonkers.

In the mornings it slants in through the high windows of his home study, making half the room convenience-store blinding and casting the other half into gloom.

When he has to do a video call or a live TV cross, Ryvchin finds himself dragging furniture around to ensure he can be seen on screen.

For artist Johannes Leak, that sunbeam is a gift: shining in from above, it brings to mind a prison cell, and the sense of confinement – of pain – he wants to bring to his portrait of Ryvchin for the Archibald Prize.

‘The work must be a painting,’ begin the rules of the Archibald, Australia’s most coveted portraiture award.

‘The work must be a portrait painted from life, with the subject known to the artist, aware of the artist’s intention and having at least one live sitting with the artist.’

Ryvchin, a writer and advocate, qualifies for another Archibald clause – that the subject be distinguished in art, letters, science or politics – thanks to a breathtakingly erudite and street-smart book on anti-Semitism, The Seven Deadly Myths, among other works. He also happens to be handsome in a Ukrainian-prince-in-exile sort of way, all sculptural nose and chiselled cheekbones; a painter’s dream.

Born in Kyiv, Ryvchin arrived in Australia in 1988 as a four-year-old refugee from the brutal Soviet persecution of Jews with his parents – both teachers – grandparents and older brother Eugene.

In Ukraine, the family had lived just a block from Babi Yar, the scene of one of the Nazis’ worst atrocities; the September 1941 massacre of more than 33,000 Jewish civilians, including old ladies and babies, who were lined up naked on the edge of a ravine and machinegunned.

In the 1980s, Alex’s parents, Tanya and Michael, had been labelled refuseniks – traitors – for applying to leave the Soviet Union, where Jews were relentlessly excluded and targeted.

They spent months in Italy before gaining entry permits to Australia.

In Sydney, there was no money. The kids spoke only Russian.

“Within a month of arriving I was put into school because my parents and grandparents had to work,” Ryvchin, now 41, says.

“So I went to Rose Bay (public) school at age four and a half. And I couldn’t communicate with anyone.

“I was getting into fights every day because I thought I was being disrespected and ignored, and misunderstandings were rampant.

“This is what happens to migrants. And within a couple of months – kids are incredibly adaptable and absorb language very well – things became a lot easier.”

Mum, an English teacher, got a job in a pie shop. Dad, a physics and maths teacher, cleaned toilets and drove a taxi.

Alex remembers huge kindness and generosity within the Soviet exile and Jewish communities and the broader Australia for this penniless clan of Ukrainians.

Not everyone was kind.

The young Alex’s first personal experience of anti-Semitism was the Austrian upstairs neighbour at a Randwick unit block who shouted death threats and Nazi slogans at the family every day.

“Why did he hate us so?” Alex has written.

“He surely would have had no coherent answer. But he knew with perfect certainty that the Jew, represented in that moment by my parents and their two boys, was something so loathsome, so repugnant, so unhuman, that he was justified in threatening repeatedly to kill a young family.”

Later, both Alex and Eugene won entry to Sydney Boys’ High, the selective public academy for brilliant young men, where one of the kids in Eugene’s year was a young Johannes Leak.

Leak and Alex didn’t meet at school – with 1200 students, it’s a big place. It wasn’t until late 2024 that Leak, now 44, called Alex up for a coffee.

By then, their link was gone.

In 2013, Eugene – a 32-year-old high-flying chief financial officer; the rational one, the mathematician of the family – died of a brain tumour, leaving his adoring younger brother Alex – the emotional, creative one – shocked and grieving.

“He was my best friend. He was the most important person in my life, I would say, at that time,” Ryvchin says.

In the 12 years since, Alex’s career as a lawyer has brought him here: co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, and the most powerfully articulate of a new generation of Australian Jewish advocates; men and women who think about what they would have done at Babi Yar, or in the Warsaw Ghetto, and who hold the crinkly hands of the Holocaust survivors, and know it’s their turn to speak up.

Ryvchin went back to Babi Yar a few years ago, and walked on the grass that covers the bodies of countless innocents.

His own grandparents escaped the massacre only because the Soviet Army, in retreat, had evacuated civilians shortly before Kyiv fell to the Germans in September 1941.

Archibald Prize 2025

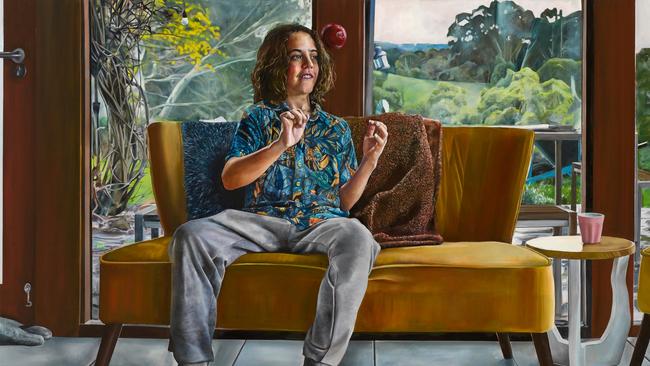

‘Afraid of the reaction’: why this painting should have made the Archibalds cut

The Archibald Prize hang is an annual dog’s breakfast. The judges need to do better.

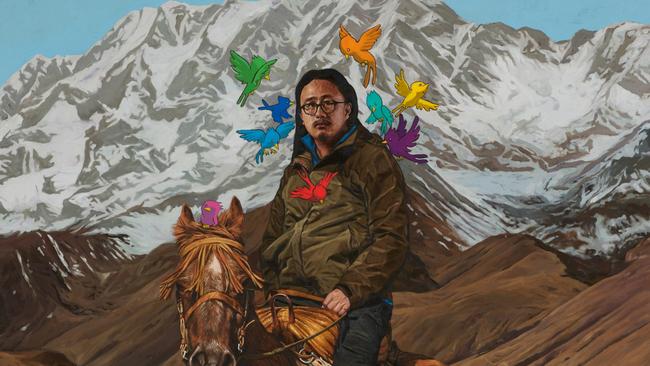

Packers pick portrait of activist artist

Pro-Palestinian activist artist Abdul Abdullah has taken out the Art Gallery of NSW’s 2025 Packing Room Prize, a curtain-raiser to the $100,000 Archibald Prize, the country’s most celebrated portrait prize.

Truth about Archibald Prize? It’s full of bad portraits

The media have for years been addicted to the cliche that the Archibald Prize is ‘controversial’, but would never dare question the inclusion of any of the truly incompetent pictures – they are generally made by minorities who are today exempt from criticism.

“The people that stayed behind were predominantly nursing mothers, the old and the sick, the frail. When the Germans entered [Kyiv] they started plastering the city with notices calling on the city’s Jews to assemble at the ravine for what they thought would be deportation. And then over two days, 33,000 Jews were massacred in that ravine.”

The Nazis got a feel for tipping bodies into Babi Yar, and over the next two years it’s estimated another 70,000 people – including psychiatric patients, Roma people and prisoners of war – were cast into the ravine.

Like all of us, Ryvchin looks at the cataclysmic moments of history and wonders: what would I have done, if I’d been there?

“I think in my youth I probably harboured romantic views of being a liberator, being a leader of some sort, saving others, saving myself,” Ryvchin says.

“But the more I’ve come to understand the nature of the killing process, the nature of Nazism, the extent of collaboration by the locals, and what actually happened – I’m convinced I would have been slaughtered like the rest of them. I would have ended up in that ravine like everybody else.”

The big reveal

All that is part of the swirl of emotion under the surface in January 2025, when the men sit beneath the morning sun for their first live sitting in that home study, Leak sketching with a pencil and paper and taking photographs.

By now, the pair are mates. They clicked instantly at their coffee meeting a few months earlier, and, as Leak sketches, the pair chat about Leak’s work, Rychin’s work and the issues they both care about.

And in March, they meet again at The Australian’s offices in Surry Hills – just hours before Leak has to load the painting in a van and drive it to the Art Gallery of NSW’s loading dock – for the big reveal.

“Oh, mate,” Ryvchin says to the visibly nervous Leak.

Ryvchin reaches out and the two men hug.

Leak laughs with relief.

Ryvchin is clearly moved by this depiction of himself – with that shaft of light drawing the viewer’s gaze to his eyes, and the backdrop a deep green that started with the shade of the study cupboards and intensified under Leak’s hand to take on an energy of its own.

He stares at the portrait, stepping close and backing away, grinning as he watches the face of his wife, Vicki, when she walks in a few minutes later to have a look.

“This is something I’ve never felt before,” Alex Ryvchin says.

“The only thing I can liken it to, I think, is my wedding day. I had the same kind of nervous anticipation on the way here. Because in Jewish tradition on the wedding day, you see the bride before she walks down the aisle, you have to identify her.

“When I saw my wife Vicki on that day, I just fell to pieces and it was a similar thing. Because in both cases, I’d beheld great beauty.

“On this occasion it was me.”

There’s self-deprecation in that – just as in Leak’s portrait, there is caricature.

Of course there is.

Ryvchin’s jaw is a little stronger, his lips a little more prominent as Leak has captured them in oil brushstrokes on the rectangular canvas, 1.2 metres wide by 1.1 metres high. His nose and eyes are photorealistic, but the cartoonist’s instinct for exaggeration cannot be suppressed.

“I suppose I’ve become quite practised at reading faces,” Leak says, “taking features and interpreting them and then accentuating aspects. And it’s just that in my cartooning work, I do it in a cruel sort of a way, you know? The object there is satire. It’s a disrespectful art form.

“This is my respectful art.

“I do feel this is what I wanted. This is the expression I wanted. It’s that combination of defiance, but also vulnerability and pain. An awareness in those eyes of the gravity of this awful time we are living in Australia at the moment; the anti-Semitism that we are seeing all over the world.

“That’s written on Alex’s face. And I noticed that before I ever met him. I saw it on his TV appearances, and I could hear it. That’s really what I wanted to capture.”

Sorrow, defiance ... and strength

“Sorrow,” says Ryvchin, when asked what he sees in the portrait of himself.

“I think particularly the bottom half of the face, the jawline. I think it’s true to the times that we’re in.

“And in my public appearances I’ve spoken for a community, but foremost I’m there as myself, as an Australian Jew speaking about my experience and my thoughts and my ideas, and there’s a sorrow to that.”

He looks back up at the picture.

“But there’s also a defiance and a strength, I think, in the chest and the posture and the jawline.”

There are parts of the portrait that Leak has left as bare canvas; on Ryvchin’s cuff and on his shirt, where the bright blankness was perfect as it was.

And there’s much of Alex Ryvchin you can’t see in this picture. The tiny Star of David he’s had tattooed inside his wrist. The fit young man who had Kanye West on his workout playlist, before West started fanboying Adolf Hitler. The concerned dad-of-three whose daughters’ daycare centre was daubed with anti-Semitic graffiti; whose former family home was set on fire and splashed with red paint in a string of racist attacks earlier this year.

The painting came together over a fortnight of intense painting – partly just because it flowed, and partly of necessity, given Leak’s commitments to the ravenous beast of a newspaper, that demands each day to be fed with mountains of words and pictures, videos and podcast episodes, ideas and emotions.

Leak’s dad, Bill, who preceded him as The Australian’s cartoonist – was one of the Archibald’s most popular portraitists, and a regular finalist.

Bill Leak’s entries, including depictions of Robert Hughes, Gough Whitlam, Donald Bradman, Barry Humphries’ character Les Patterson, Tex Perkins and others – won Packing Room honours and People’s Choice awards – but never the big prize.

Johannes first entered the Archibald in 2021 with a depiction of conservative Aboriginal politician Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, which was not selected for the finalists’ exhibition – something that prompted outrage from some commentators.

Neatly, that was matched by outrage from others when the State Library of NSW subsequently bought Leak’s portrait of Price for its own collection. Some Library staff told The Guardian they didn’t consider Price a significant NSW figure.

“It just seems, in the language that we use these days she [Price] is considered to be a controversial figure, a polarising figure, even though she’s just a wonderful human being,” Leak says.

“I’m sure that played a role; I mean that the Archibald has been captured to some degree by progressive politics.

“And I don’t think I’m sort of expressing anything out of left field there. I think that’s well and truly understood.

“But why try and go with the grain when you can draw attention to people who I think a lot of Australians, ordinary Australians, do support?

“They understand people like Jacinta, and we saw that during the referendum. She resonates with ordinary people.

“Just because a particularly activist part of the arts community has aligned themself with the pro-Palestinian cause, doesn’t mean that hundreds of thousands, if not millions of ordinary Australians are not looking at Alex and thinking: ‘Isn’t he wonderful?’ You know: ‘Isn’t he making sense?’

“The Archibald should, I think, reflect a broader cross section of artists perhaps, and the Australian experience and the Australian character – rather than a narrow, progressive, activist agenda.

“But that’s why we enter – and see how we go.”

When the Archibald finalists were announced on May 1, Leak’s portrait of Ryvchin was not included.

Anti-Israel sentiment in the arts

In the 18 months since the October 7 massacre of Israelis by Hamas, and the subsequent pounding of Gaza by Israel, it’s been arts organisations in Australia where anti-Israel sentiment has been loudest. Keffiyehs have been worn. Jewish artists have been uninvited, deplatformed, doxxed.

“As someone who writes,” Ryvchin says, “I know what a piece of art – if I can call my writing that in a lavish way, you know – it’s something that comes from deep within you.

“You’re revealing yourself and you want people to interact with it, to consume it, to debate it, and to be frozen out and shut out merely because some of those views – or how you are perceived as a person – doesn’t align with a particular political agenda?

“I think it’s a travesty.

“The Jewish people numerically are minuscule, there’s little more than 100,000 Jews in this country of 25 million.

And we can’t interact with ordinary Australians that much, because there’s not that many of us.

“The way that we reveal who we are, the way that we put forth our ideas and show our humanity is through our art, through plays and literary works and paintings.

“And so when Jews get frozen out and subjected to boycotts and shadowbans, it’s a way of expunging Jews from visibility and society.

“I mean, most people haven’t met a Jew, but they may have seen a work of (Nobel Peace Prize laureate and author) Elie Wiesel, or (memoirist) Isaac Bashevis Singer or Steven Spielberg or Jerry Seinfeld. And so we need to keep fighting for this.”

The deplatforming has come despite a long history of Jewish philanthropy in the arts.

“Jews have contributed to every aspect of life in this country, and not for any tactical or nefarious reason, as our detractors would have people believe,” Ryvchin says.

“It’s because we deeply love this country and we want to contribute to it. And you know, I speak to that generation that came here after the Holocaust with nothing. Literally nothing, penniless and having lost their families in the camps or the killing fields, and they made something of themselves because of, firstly, their own character, but also because of what this country allows people to do and to achieve.

“And they’ve always given back, they’ve always built up this country. They’ve always contributed to the arts and to medical research and all of these fields. And there is a terrible irony to the fact that these people who have contributed so much out of a love for this country are now being rejected.”

Would Alex like to have it on his own wall, perhaps beneath that troublesome sunbeam?

“I don’t know what my wife would think about having two of me in the home,” he laughs.

“But I could gaze at that all day.”

The Archibald Prize winner is announced on May 9. We will be covering the announcement live at theaustralian.com.au, where right now you can see a video of Leak’s artwork coming to life, shot and edited by our head of video, Johnathan Barhoumeh. If that’s still not enough, Leak and Ryvchin can be heard in a special edition of our podcast The Front, live now wherever you get podcasts.

The Archibald Prize winner is announced on May 9. We will be covering the announcement live at theaustralian.com.au, where right now you can see a video of Leak’s artwork coming to life, shot and edited by our head of video, Johnathan Barhoumeh. If that’s still not enough, Leak and Ryvchin can be heard in a special edition of our podcast The Front, live now wherever you get podcasts.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout