What’s my name? NGA’s exhibition shines a light on women

The National Gallery of Australia’s Know My Name exhibition asks more questions than it answers.

The title of this exhibition is rather unfortunate: apart from its plaintive tone, with inevitable echoes of self-pity and resentment, it recalls Sir Thomas Browne’s comment in Urn Burial, chapter 5 (1658), on the philosopher Cardan, who had said he did not care if his work and life were forgotten, as long as his name was remembered: “To be content that times to come should only know there was such a man, not caring whether they knew more of him, was a frigid ambition in Cardan.”

Besides, there is the implication that these artists have not only been carelessly forgotten but almost suppressed. This is simply not true. Female artists have faced many obstacles in the past, particularly in obtaining training, but those who had talent were appreciated because of their scarcity. Artemisia Gentileschi, about whom I wrote recently, was famous precisely because she was a female painter, and made the most of that fact. With the passage of time, however, almost everyone who is not in the first rank or one who has changed the direction of art history is more or less forgotten — men and women alike.

To quote Urn Burial again: “But the iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her poppy, and deals with the memory of men without distinction to merit of perpetuity. Who can but pity the founder of the Pyramids? Herostratus lives that burnt the Temple of Diana, he is almost lost that built it; Time hath spared the Epitaph of Adrians horse, confounded that of himself. In vain we compute our felicities by the advantage of our good names, since bad have equal durations …”

So one wonders what the purpose of this exhibition really is, apart from another demonstration of right-thinking zeal from the management that brought us the new hanging of the 19th-century Australian collection and that has downgraded the Asian collection so drastically. The best of the female artists displayed here are already well represented in the exhibitions of their periods; there are no revelations of brilliant talents that have lain hidden and ignored.

Some artists who do deserve attention, however, are poorly displayed, and in a way that will make it hard for anyone to discover or rediscover them. This is the case, for example, with Agnes Goodsir (1864-1939), an Australian expatriate who lived in Paris — at 18, rue de l’Odeon to be exact — for most of the 1920s and 30s until her death in 1939. She made a good living as a portrait painter — she did a seemingly lost portrait of Bertrand Russell and was commissioned to paint Benito Mussolini — and many of her pictures probably still are hanging in houses in Europe or circulating, unattributed, through minor art auctions. Most of her surviving paintings are of her girlfriend, Cherry, assuming various characters, as we see here.

Goodsir’s paintings are crowded at the top of a dense wall of pictures, assembled into a would-be salon hang; unfortunately the disparity of media as well as quality reduce the group to something of a visual cacophony.

And if that were not enough, anyone trying to pick their way through the jumble of works — in which there are, if one could find them, many other fine pictures — is subjected to the relentless drone of an adjacent video work in which a voice smugly rehearses some of the best-known moments in the history of performance art, like an undergraduate student who has only just found out about them.

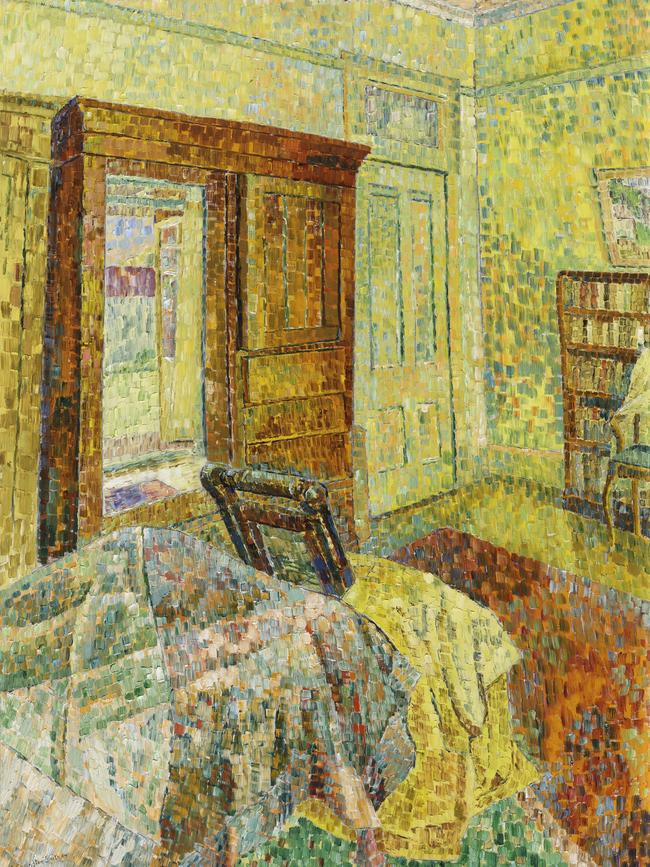

Among the other genuinely interesting artists who thus find themselves doubly short-changed — by overcrowding and by gratuitous and appallingly distracting noise — are Grace Cossington Smith (her Sock Knitter from 1915 is lost in the crowd, although the artist is given a second chance elsewhere), Vida Lahey, Violet Teague and Stella Bowen. These are all women who should have been given space and could have benefited from intelligent explanatory labels, helping the viewer to understand their lives and careers.

Instead we proceed into an adjacent space to find a mixed group of works under the shopworn academic rubric “performing gender” — especially questionable since these works are more obviously “performing art history” and “performing genre” than anything else. The space is dominated by works that, once again, have been regular staples of exhibitions for decades and are in no sense undiscovered or unrecognised.

More interesting, for this reason, are the things that are less usually seen, including a reclining nude by Bowen (1927), who evidently has been looking at Modigliani.

Nearby is another nude by Janet Cumbrae Stewart (1883-1960). The label alludes to the way her work has been questioned for directing a male gaze at the female body, but this is not because Cumbrae Stewart’s gaze is alienated or inauthentic. It is because she was a lesbian whose work is entirely made up of pastels that express a painful and almost indecent sensual yearning for her young naked models.

Cumbrae Stewart is another artist who, though limited, deserves a little more attention. An exhibition was devoted to her at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in 2003. There is a touchingly girlish and vulnerable self-portrait at around the age of 28 in the National Library, and it would be interesting to know if one of her unidentified portraits is of her companion, the formidably named Miss Argemone ffarington Bellairs, known to her friends as Bill.

Nearby is an interesting picture by another minor artist, Freda Robertshaw (1916-97), the pupil and assistant of Charles Meere; he was a minor painter too, but as the fortunes of art history would have it, produced one picture that became a kind of symbol of its time: Australian Beach Pattern (1940). Robertshaw subsequently produced her own version, Australian Beach Scene (1940). Meere’s composition subsequently became the basis of several re-creations, variations and pastiches.

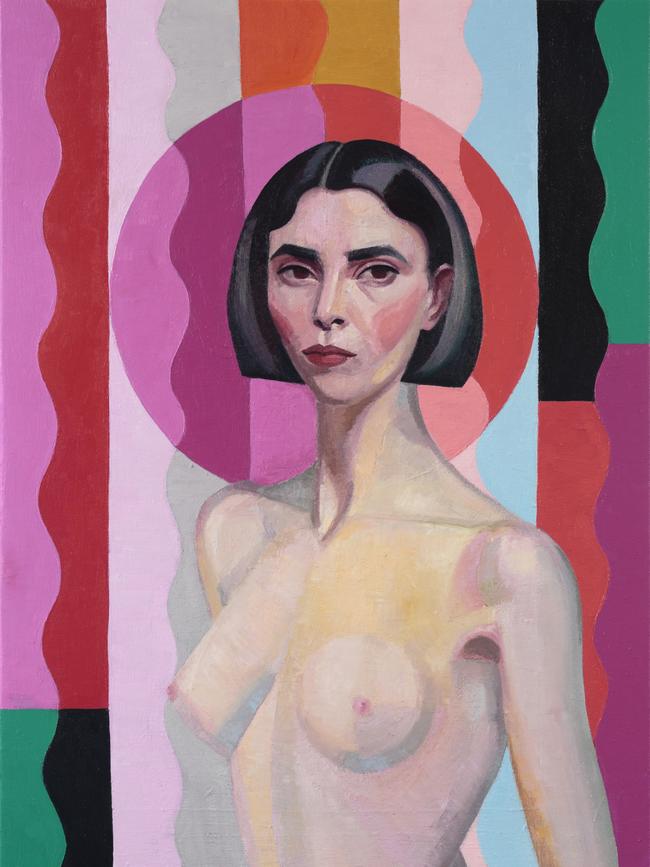

With a refreshing lack of self-consciousness, Robertshaw represents herself in a full length self-portrait at about the age of 28 (1944), naked except for the sandals that give her a little extra height and subtly change her posture. Although readymade labels such as “performing gender” add little to our understanding of this picture, it is interesting that she and before her at least a couple of other female artists painted naked self-portraits — notably Dorothy Thornhill (or Dundas after her marriage to Douglas Dundas) who represented herself as a Resting Diana (1931, NGA) — at a time when no male artist seems to have done the same.

Perhaps inspired by the famous mise-en-abyme compositions of earlier artists, most notably van Eyck in the Arnolfini Wedding (1434) and Velazquez in Las Meninas (1656), or perhaps simply struck by the fortuitous presence of a mirror on the wall behind her, she ends up playing a complicated game with reflections. In the painting, the mirror hanging behind her gives a simultaneous view of her back. But, less intelligibly at first sight, it also includes a frontal view; this latter, of course, must be the mirror behind her reflecting the image that she is working from in the full-length mirror that we cannot see but which must be standing in front of her.

Rosemary Laing's photographs of women falling through space evoke a very feminine experience and occupy a vast wall further on in the show, while in Anne Ferran's series Scenes from the Death of Nature (1986), young women recline, lounge or seem to swoon in long white robes based on the classical Greek chiton. Again we can sense the discomfort of the label writers, who could not ignore this work but wished that it had been less passive in tone: “at the time of making this work, Ferran was interested in feminist theories that she felt were too much about ‘the refusal of pleasure’ and that failed to locate opportunities and spaces for women’s own desire and visual enjoyment”.

At first sight, we may be reminded of the robed female figures of the Parthenon frieze that inspired Henry Moore’s reclining women sculptures. But the Parthenon women are full of energy and physical strength, even when relaxed. These figures, on the other hand, evoke a very different and more romantic sensibility of longing, waiting, yielding and surrender.

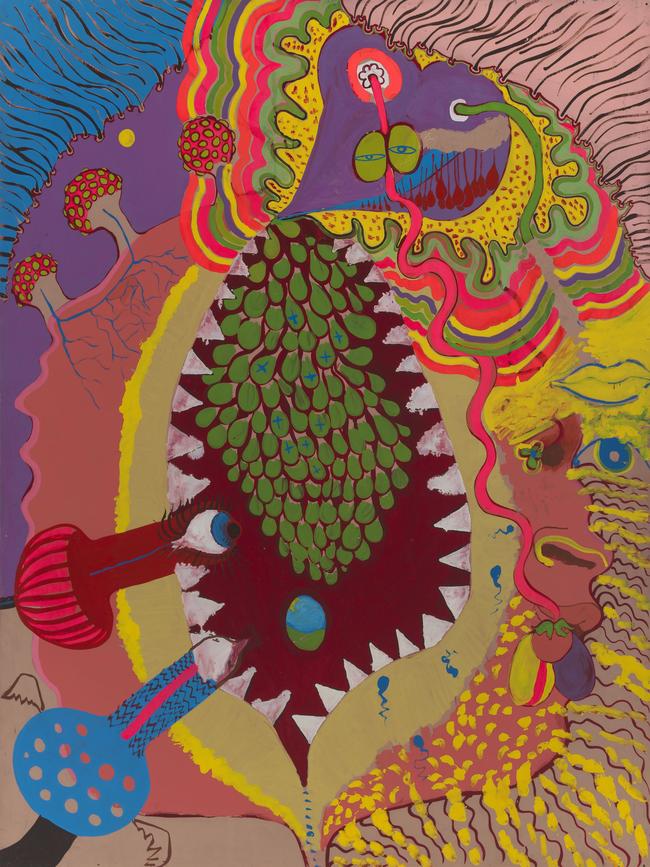

A large room devoted to “Colour, light and abstraction” includes several large abstract paintings that, like most of the work made in that style, have aged badly.

More interesting are the figurative pictures such as Cossington Smith’s painting of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1930) or her Lacquer Room (1936), which shows the newly opened cafe at David Jones in Sydney, decorated in bright modern reds and greens, and frequented by the well-to-do ladies who would later meet for lunch at the department store’s restaurant overlooking Hyde Park. There is an Olive Plantation (1946) by Dorrit Black that makes an interesting pattern from a distance but doesn’t really reward a closer examination. There is also a picture of the Harbour Bridge by Black (1930). On the label Black is quoted as saying that “realistic painting has proved to be a blind alley”, a pronouncement as breathtaking in its naivety as in its presumption, especially coming from someone with so little claim to speak with such authority about the art of painting or its history. This is just another example of the casual arrogance that became so common in 20th-century art teaching.

The label comments that Black’s picture is “widely considered to be the first cubist landscape made in Australia”, but her cubism has nothing to do with the pictures of Picasso two decades earlier in the years before the Great War; this is a kind of pale neo-cubism reduced to a decorative academic formula by the postwar French epigones of the movement such as Andre Lhote and Albert Gleizes, who passed on their tepid recipes to a generation of enthusiastic young women such as Black and others.

Other rooms in the exhibition include the large semi-abstract paintings by Aboriginal female artists that became among the most commodified and fetishised form of art produced in Australia in the past few decades. They have a bland decorative quality that is easily digested, but also come with the assurance of underlying spiritual significance — a combination irresistible to collectors and the art market.

There are also several other artists of questionable merit, but who continue to be favourites of the contemporary art academy, including some who have done little for decades but who, thanks to some provocative gesture a half-century ago, have been granted lifetime membership of the approved contemporary art list ever since.

Meanwhile, many contemporary female artists of real merit, mostly painters, are completely unrepresented and may as well not exist because they don’t fit the template of approved contemporary art. Ironically, these are the individuals whom the truly interesting painters in this exhibition would be most likely to recognise as their peers.