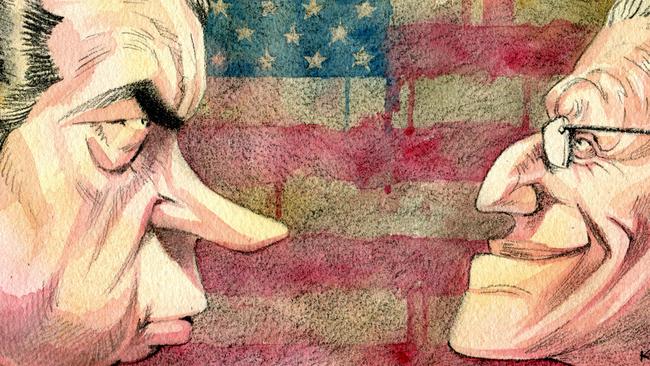

Watergate reporter uncovers fresh dirt on the paranoid presidency of Richard Nixon

Bob Woodward’s fresh portrait of Richard Nixon sheds new light on one of the great political scandals.

Bob Woodward, whose reporting of the Watergate break-in and cover-up led to Richard Nixon’s downfall, laughs when asked if he recalls the phone call from The Washington Post newsroom early on a Saturday morning in June 1972 asking him to look into the so-called “third-rate burglary”.

“It was a beautiful day,” Woodward tellsReview. “I’d worked at the Post for nine months. I was the night police reporter and they knew they could call me in at any time. I think they thought: ‘Who would be crazy enough to come in on such a beautiful Saturday morning?’ ”

Woodward contributed to the original Post report by Alfred E. Lewis published below the fold on page one that reported five men were arrested at 2.30am breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex in Washington, DC.

“It was unusual to have five burglars in business suits with sophisticated electronic eavesdropping and photographic equipment,” Woodward says. “I went to court for the arraignment of the burglars. One of them whispered to the judge that he had worked for the CIA. That immediately got me thinking: ‘What is this? Where did this come from? What’s behind it? Who’s behind it?’ ”

Woodward’s reporting with Carl Bernstein changed the course of history — but not immediately. Nixon went on to win one of the largest election landslides in November 1972. Woodward and Bernstein continued their investigations, enduring attacks from politicians and other media outlets for pursuing the story.

More than four decades since Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, Woodward has written a new book — his 18th — which offers new insights into Nixon, his White House and the scandal that destroyed his presidency.

In July 1973, Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield was asked during his testimony to the Senate committee investigating Watergate if he was “aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president”. Butterfield, with a look of worry across his face, paused and said: “I was aware of listening devices, yes, sir.”

In The Last of the President’s Men (Simon & Schuster), Woodward tells Butterfield’s story and what came before and after those eight words that “shocked the world”. The discovery of the secret taping system, installed with Butterfield’s help, sealed Nixon’s fate. “Without that evidence, Nixon certainly would have been able to stay in office,” Woodward writes.

Butterfield joined the Nixon White House after the November 1968 election. He was stationed in Australia as a senior US military officer attached to the air force. Butterfield knew incoming chief of staff HR “Bob” Haldeman as they had been students together at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the 1940s. Butterfield secured a job as Haldeman’s assistant.

He saw Nixon up close; sitting in on meetings and following up on presidential directives. When Butterfield left the White House in March 1973 “with a jumble of thoughts and emotions”, he took 20 boxes containing thousands of White House memos. Many are included in the book.

Butterfield’s story largely has remained untold. A draft memoir, provided to Woodward, was never published. He has refused most interviews. Indeed, Woodward asked for an interview in the 1970s. However, last year and this year, Butterfield gave Woodward 46 hours of interviews for the new book.

“He’s the guy who has this perfect seat and he can tell what Nixon’s up to and Nixon’s attitudes,” Woodward says.

“Butterfield was the first one to see him in the morning, last to see him at night — about as close as you can get to Nixon.”

The fresh portrait of Nixon is utterly captivating but rarely flattering. Woodward says Butterfield’s memos and interviews give us a deeper understanding of the embattled president. His paranoia, vindictiveness and awkwardness are stark. “He was even more haunted than I thought,” Woodward says.

Butterfield recalls Nixon “was happiest when he was alone”. His lunch would always be cottage cheese with pineapple. In the evening, Nixon would often walk across the street to the Executive Office Building, eat dinner alone, have a drink and “sit there with his yellow legal pad” jotting down notes. “He wouldn’t even take his jacket off until around 10.30 at night,” Butterfield recalls.

Then there are Nixon’s lists of “enemies” and “opponents”, and the “freeze list”.

Nixon told Butterfield to keep them updated and circulate them regularly to staff. “As he got older,” Butterfield says of Nixon, “instead of mellowing, the neuroses intensified and he lumped them all together.”

Woodward relays Nixon’s horror at seeing White House staff with pictures of other presidents, such as John F Kennedy, on their desks.

“Nixon calls it an infestation and insists that they be replaced with pictures of him,” Woodward says. “If somebody had told me that, I would have laughed. But it’s real. It was a farce and Butterfield had to write him a memo titled ‘Sanitisations of the staff offices’.”

The memos expose the deception at the core of the Nixon White House, particularly over the Vietnam war.

“There is one memo in Nixon’s handwriting about Vietnam where he says all the years of bombing has achieved nothing — it achieved ‘zilch’,” Woodward says. “That takes history and turns it on its head and because Nixon always said that the bombing was effective.”

In February 1971, Nixon ordered the secret taping system be installed. It fell to Butterfield to arrange it. “Nixon didn’t think they would ever be revealed,” Woodward says.

“If Butterfield didn’t tell, nobody would have ever known and then Nixon would have stayed in office because without the tapes Nixon probably survives.”

Moreover, if Nixon had destroyed the tapes — which he suggested to staff at various times — he could have remained as president, Woodward says. He also suggests if Nixon had “come clean” and apologised for Watergate, maybe he could have recovered.

The Woodward-Bernstein reporting focused on the attempt to cover up the linkages between the Watergate burglars and Nixon’s campaign committee, which then infested the White House.

“What led to Nixon’s downfall were the cover-up and the repeated denials and then the explicit tape recording — the so-called smoking gun tape — which shows Nixon ordered the CIA to get the FBI to limit their investigation,” Woodward says.

Woodward’s key source was FBI deputy director Mark Felt, who outed himself as “deep throat” in a Vanity Fair article in May 2005. Woodward later published his own account of Felt’s role in The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate’s Deep Throat.

“I thought he would keep it secret forever,” Woodward says of Felt. “I remember seeing a video of him standing on the steps of his house with his walker, I think he was in his pyjamas, and he had a smile on his face the likes of which I had never seen … he did the right thing.”

In 1976, Woodward and Bernstein’s bestselling book, All The President’s Men (1974), was made into a movie, cementing the legend of the two intrepid reporters who brought down a president. Who wouldn’t want to be portrayed by Robert Redford? “I thought they did a very good job,” Woodward says. “But you have no idea how many women I’ve disappointed.”

There was “always tension and sometimes disagreement” with Bernstein, he says, “but we became friends”. Woodward still has a passion for reporting but worries about aspects of the modern media. “Being a reporter is a great job,” he says. “You get to make momentary entries into people’s lives when they’re interesting, and get the hell out when they cease to be interesting. The emphasis is on what we don’t know, what has meaning, what’s hidden, how do we get at it, how do we explain things in a complicated world to people.”

But Woodward questions if the media has the patience or resources to uncover a scandal such as Watergate today. He is concerned that some reporting and analysis has become shallow. “You are not going to get to the bottom of Watergate with 140 characters in tweets,” he says. “So you’ve got to have owners and editors and reporters who are patient and dedicated.”

He is surprised by what we are still learning about Nixon from his tapes, previously undisclosed documents and new interviews. “He should never have been president,” Woodward says. “It was tragic for him and tragic for the country. But I guess the message, particularly in this new book, is that history is never over.”

Woodward has a warning, however, for new generations unfamiliar with Watergate: it could happen again. “That’s the problem; there is too much secret government,” he says.

“The message managers have undue influence in government and they try to keep things from coming out.”

When I suggest this is a frightening prospect, Woodward adds: “We’d better be frightened, particularly when it comes to being re-elected or elected to political office. The hunger for power when it intersects with a war, it’s a concoction for real trouble.”

Bob Woodward’s The Last of the President’s Men is published by Simon & Schuster ($49.99 hb; $19.99 e-book).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout