Volunteers for the Vietnam War

Michael J Malone explains why he decided to sign up for duty during the Vietnam War.

I was born in Binnaway, in country New South Wales, in April 1947, and I lived a typical knockabout country kid’s life: playing rugby, looking after the cows, getting into strife. When I was 11, my parents, Ned and Joyce Malone, packed me off to boarding school at St. Stanislaus College in Bathurst, where I learned some tough lessons that would serve me throughout my life. After school, I floated around from job to job, and by 1965, I was 18 years old and aimless. I had left a job in the wool store in Miller’s Point, and moved to an aluminium production plant at Granville, which was excruciatingly boring but at least the pay wasn’t bad. I was there for around 12 months, enough time for me to vow never to find this sort of work again. My mate Mick Ryan suggested I join him working at the vinyl tile manufacturer, CSR, in Concord, but that turned into yet another shit job. I didn’t last long. I hated shift work.

I turned 19 in April 1966, and was having real doubts about what I should do with my shitty life. I was knocking around with a few losers at home and wasn’t getting on at all with my father, who seemed very withdrawn and cranky most of the time. After a particularly savage confrontation, I punched him hard in the nose, jumped the back fence, and bolted. I stayed with a mate for a couple of days, and when I came back, expecting slings and arrows, nothing was ever said.

I had some things to keep me distracted. I had my first car, an old Morris 8 convertible, by this time, and used to head down the coast with another bloke, big Mick, with two surfboards sticking out the top.

Later, I got hire-purchase to buy a new car, and I chose a new Japanese-made little Isuzu Bellett. It was lovely owning a brand-new car in the ’60s. The girl up the road, who I was madly but secretly in love with, was even impressed. My lout mates couldn’t believe their eyes when they all piled in for a spin. I washed that car within an inch of its life and kept it humming.

But still, I had no real direction.

Then the Battle of Long Tan happened in South Vietnam, on 18 August 1966. This was a huge battle fought by DCompany 6RAR in a rubber plantation against the enemy 275 Regiment, which was planning to attack the Australian base at Nui Dat, still in the process of being established. We lost 18 Killed in Action in the battle, while the enemy lost probably 300 plus, with many more wounded.

Reading of the amazing heroism prompted me to reconsider my purposeless life up to now, and I decided to do something about it. I downed tools and headed for the army recruiting office.

On the way home on the train, I had plenty of time to mull this over.

Was this the right thing for me? I read in the papers every day that our soldiers are being killed in Vietnam: why would I want to put myself in that scenario?

I’d made my mind up by the time I got home. Dad was in the lounge, Mum in the kitchen.

“Dad, I want you to sign these papers, please.”

“What are they?” he said.

“I want to join the Army,” I said. “These are the papers because I’m under-age.”

“No, I’m not signing them. Wait till you’re 21.”

I arced up at that, and said: “Fine, if you don’t sign them, I’ll forge your signature and you’ll never see me again.”

He signed and gave the papers to me. “I hope you know what you’re doing.”

I said: “I hope so, too.”

First hurdle negotiated, all I had to do now was to keep out of trouble around this shithole of a town, pass the Army psych and other tests to prove I wasn’t a total prong, and that I’d be of use to the Army.

The four weeks seemed to fly by at work: my mind certainly wasn’t on the job; it was on the prospect of Army service.

Dad was wounded by shrapnel in Alamein and shot through the shoulder in New Guinea, but never spoke of those incidents: it was all the funny stories that he spoke about. When it was time to attend the recruiting office in Pitt Street, Sydney, I was as nervous as all get out. I got there early and sat on a park bench for 20 minutes to wash some time off. At the designated time, I went into the recruiting office waiting room and met two men who would become my firm mates, right through rookie and infantry training. When it was my turn, I was directed into a room with a sergeant behind the desk.

“Sit down and pay attention,” he said.

There were a series of charts on the desk, which I soon found out were “Rorschach” tests: a series of random ink blobs, which the psych person could determine your personality or some such bollocks. Then it was a hearing test, an eyesight test, and various questionnaires to do with family, proclivities, and if I drank or smoked. Then it was into another room with a doctor who cupped my bollocks and said “cough”. He also listened to my heart, stuck his finger up my nether region, and looked at my feet and knees. I told a serious lie among all this when I said I’d never had asthma.

If I’d said yes, then that would have been the end of my military career before it even started. I thought I was on pretty safe ground because I’d always thought I’d grown out of it years ago. Then it was back into the waiting room to await the verdict. A couple of hours later, I was told I’d done well, and at the end of it all, I was told to report to Eastern Command Personnel Depot (ECPD) at Watson’s Bay in two weeks, where I would be prepared for the trip south to the Recruit Training Battalion at Kapooka (1 RTB), outside Wagga Wagga in country NSW.

Home again I found my father was actually quite pleased that I’d made it although, being a staunch Labor Party man, he wasn’t too keen on the prospect of me going to Vietnam for what Labor called “Bob Menzies’ War” which was raging by this time: my Uncle Terry was preparing to go with the AATTV, and my cousin Peter had joined at 17 and was slated to go. Mum was on edge but was pleased I was going to do something with myself, having let her down with my education.

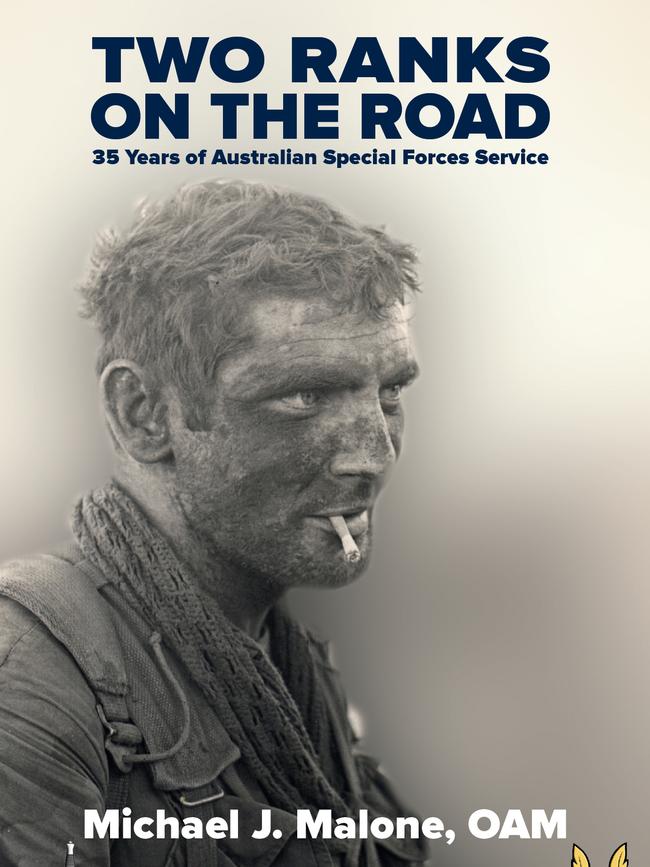

It would be six decades before I’d sit down to write my memoirs of my time in the Australian military. The title of my book – Two Ranks on the Road – comes from the exact moment I realised, at 20 years old, I was playing with the big boys: running helter-skelter down a bush track in boots, green trousers, and rifle, not knowing how far we would run, but giving it my all.

The “two ranks” formation (as opposed to the more formal “three ranks”) defined my Army career.

One problem I’ve encountered: my memory is not as sharp as it once was. I regret never keeping a diary, but we were forbidden to do so by virtue of the unit we were in.

I’ve always prided myself on my memory. I studied ancient and modern history in school and had no trouble remembering all sorts of dates, battles, emperors, kings, and seminal turning points of history. This project, however, has demonstrated how my memory has deteriorated ever so slightly, and as I approach my 77th year, I was pleased to be engaged in it, to give my memory a jog. I included a lot of army jargon; those who need some help should go straight to the glossary at the back! The military language becomes second nature after a while, but I hope I have written this in a way to be clear to most.

I hope readers will understand that I enjoyed my service greatly: I met some outstanding soldiers of all ranks who showed great leadership, mateship and resilience and led me in the right direction. There was a small minority who decided to make life hard for a few of us, but I even learned from their negative vibes. As I rose through the ranks, I had the chance to mentor countless young soldiers who seemed to respond to my particular methods and approach, and I would like to think that my book might serve as a record of the importance I placed on bringing impressive young Diggers along, and I hope this memoir goes some way to explaining the life of a simple soldier.

This is an edited extract from Two Ranks On The Road (Imprimatur Books) by Michael J. Malone, to be launched at Boffins Books in Perth on Sunday 21 April. Make your booking online.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout