Unearthed: the discoveries that turned ancient Egypt on its head

As Melbourne prepares to unveil the biggest exhibition of Egyptian antiquities seen in Australia, we dig into the priceless treasures contained the British Museum’s storage rooms. What did we find?

On a long, covered table in a second-floor collections room at the British Museum, a selection of ancient Egypt’s most important artefacts are getting some air. The precious items have been extracted from storage and presented – like objects at a garage sale – for inspection, and resident curator Marie Vandenbeusch can barely contain her delight.

“It’s so nice to see them out,” says Vandenbeusch, the British Museum’s curator of funerary culture of the Nile Valley in the Department of Egypt and Sudan. “Out and into the world again, they look … so, well, different.”

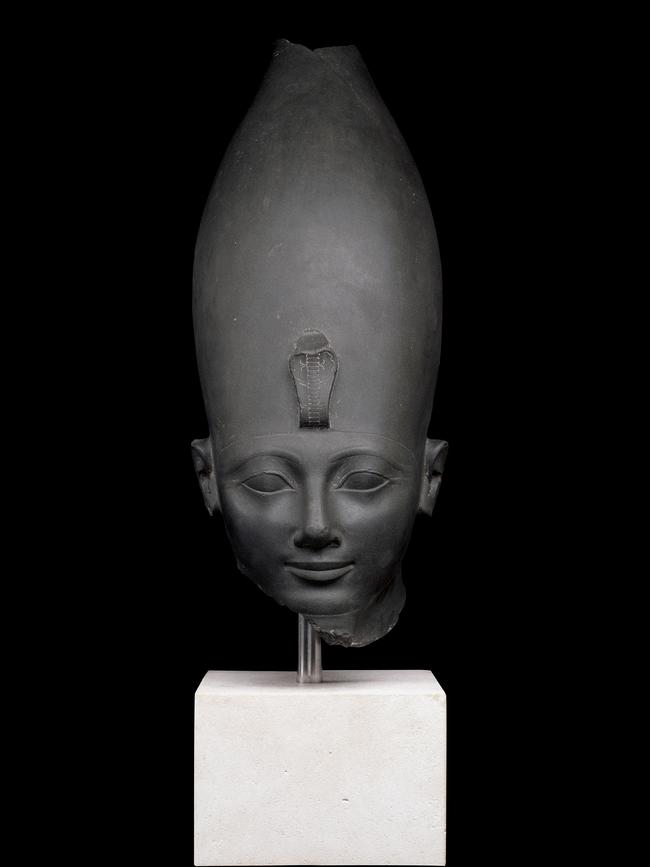

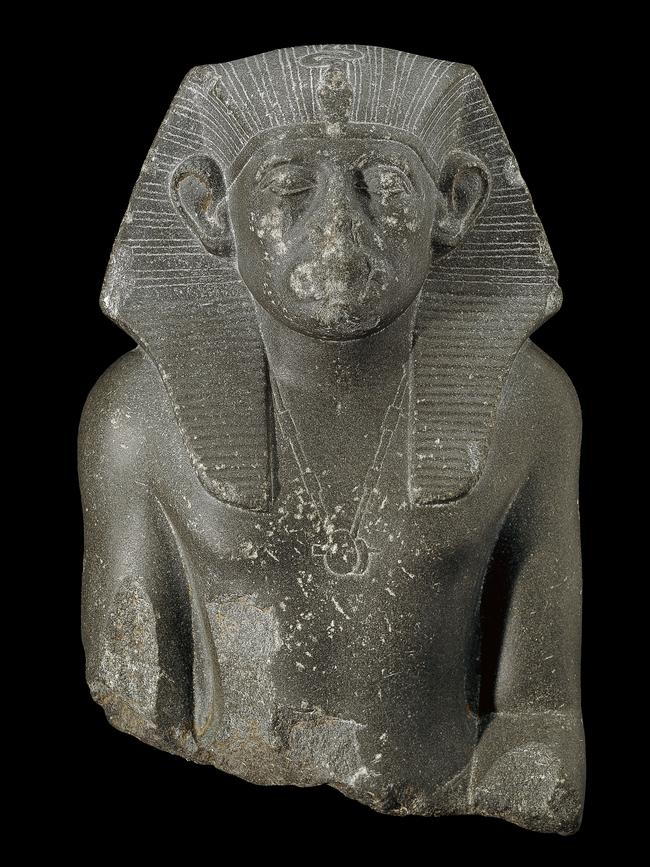

In front of us are two ancient busts – a statue from 1874BC-1855BC of Senwosret III, the pharaoh who reigned during the 12th dynasty, and a carved relief dating to 1500BC-1295BC of Mentuhotep II, who ruled during the 18th dynasty.

Vandenbeusch glides briefly past the pharaohs (“We’ll come back to those. Promise”), and carefully picks up from the table a small axe. The tool – or is it a weapon? – is in remarkable condition, all bevelled edges and leather-bound haft. It looks as though it could still do some damage; no mean feat, given it was forged sometime between 1650BC and 1550BC.

“It is the kind of historical object through which you can really start talking about ancient Egypt as a place that was not exactly the most peaceful on earth,” she says.

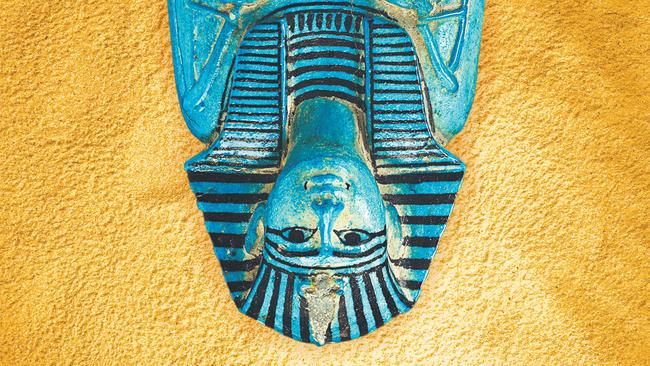

Alongside the axe is another example of implausible craftsmanship, albeit a less violent one: a small, faience spacer-bead plaque – a necklace decoration – featuring intricate carvings of gods Horus and Thoth. The plaque, which dates to the intermediate period of 1069BC-656BC, is characterised by a deep shade of Persian blue, still somehow luminescent 3000 years after it left the furnace. The hue – all but deified in ancient Egypt as the colour of the heavens, the dominion of the gods – is even more vibrant in a dramatic glazed tile inlay Vandenbeusch shows Review. Its surface reveals the gilded nomenclative variants of Amenhotep III.

“The blue is absolutely incredible,” she says of the tile’s colour, made by grinding silica, limestone and water into a paste before firing. “The gilded tiles came from above a door frame or on a piece of furniture. But you must not imagine the place it came from as just piles of bricks. This has come a from a place of true magnificence.”

As one of the ancient world’s leading museum curators, is this the thing that most inspires Vandenbeusch: the cultural gravity of history with which she is daily acquainted?

“Well, yes, but one thing I really like about the period is the humour,” she says. “We don’t often think of ancient Egypt in those terms.”

She takes Review across the table to a limestone ostracon, dating to 1295BC-1069BC. The shard of stone or ceramic shows a baboon sitting at a table eating from – perhaps stealing from – a bowl of fruit. The ostracon was excavated early last century from the historically rich Deir el-Medina region on the west bank of the Nile. It is the place that was home to the artisans who built the extravagant tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the final resting place of Tutankhamun, Seti I, and Ramses II, among many others.

“Basically, these ostracons tell us a lot about life at the time, either as inscriptions or decoration. Some were also used to make jokes. In this case, we have a baboon eating a bowl of figs. It is quite a funny scene, and there’s something about that idea I find quite powerful. Something quite familiar about our shared history.”

The table-laid items – pieces either commissioned by or created for the great rulers of the ancient world – are part of a vast collection of artefacts making the journey this month from London to Melbourne. More than 500 pieces from the British Museum will from June 14 fill the National Gallery of Victoria when Pharaoh, the largest and one of the most significant exhibitions of Egyptian history to reach Australia, is officially opened.

Curated by Vandenbeusch, the show will comprise sculptures, coffins, funerary objects and a large collection of jewellery, spanning 3000 years of Egyptian history.

If Pharaoh sounds big, it’s because it is. In fact, it is the largest international exhibition the British Museum has presented in its 270-year history.

The show will feature works from the minuscule – a 5cm ivory label depicting the first-dynasty King Den – to the monumental – a hieroglyph-carved limestone wall measuring 2.5m x 3m retrieved from a mastaba tomb. (The wall, which had lain in pieces for a generation, has for the NGV show been painstakingly rebuilt by British Museum restorers, Vandenbeusch tells Review).

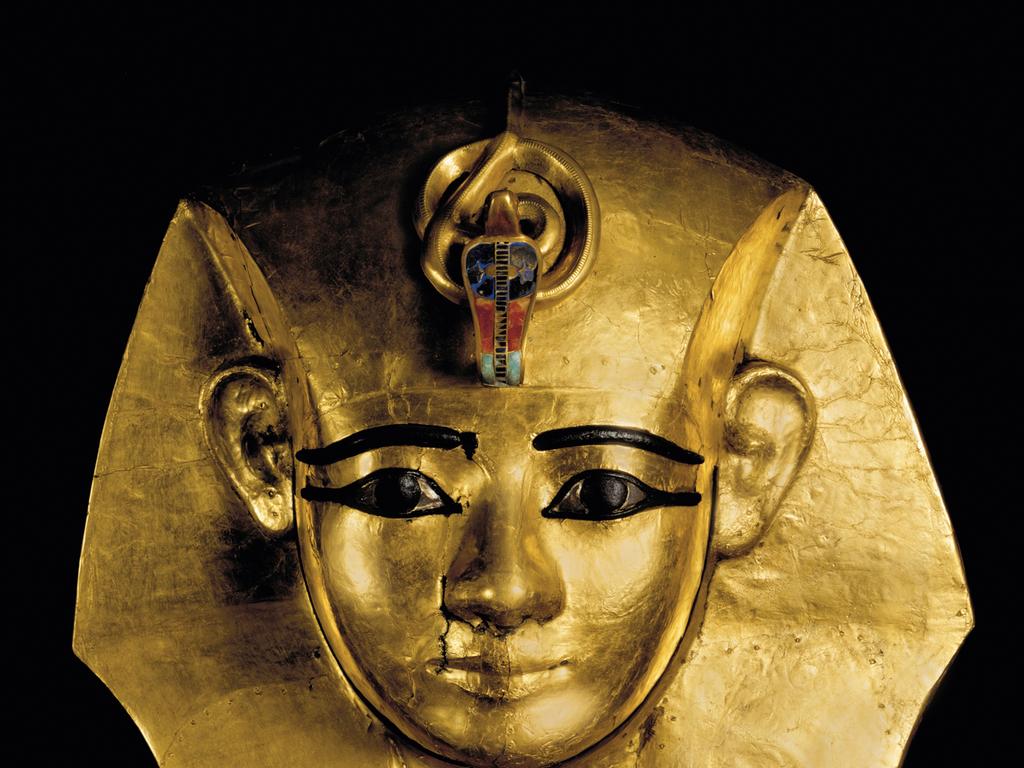

The show also will host the museum’s famous carved siltstone Head of Tuthmose III, the pharaoh responsible for the greatest expansion in the empire’s history. Further, a pair of large sphinxes and the two-tonne red granite Hathor Capital (874-850BC) will feature alongside a figure with whom Australians have become recently well acquainted. Ramses II, the subject of a 2023-24 survey at the Australian Museum, will be represented at the NGV in the form of a 2m-tall statue, dated to 1279-1213BC, portraying the king as a high priest; it will be complemented by a 1.5 tonne monolithic fist – once part of a colossal statue of the pharaoh – recovered from the historic temple of Ptah in Luxor.

Egypt fever

Australia is in the grip of Egypt fever. Indeed, in these pages last year we claimed as much when it was announced the NGV, the National Museum of Australia in Canberra and the Australian Museum in Sydney all were holding exhibitions dedicated to the period. Ramses & the Gold of the Pharaohs, at director Kim McKay’s Australian Museum, last month became the most visited exhibition in that institution’s history, selling more 350,000 tickets. Discovering Ancient Egypt at the Canberra institution runs until September this year; Review understands it is also doing strong numbers.

The NGV’s Tony Ellwood, no doubt, is expecting high traffic through the St Kilda Rd gallery’s doors when the curtain is raised on the Winter Masterpieces exhibition.

Ellwood says while he is hoping to attract a new generation of visitors, the exhibition’s focus would not waver from its intention.

“The NGV’s exhibition will place precedence on the exceptional craftsmanship of the ancient Egyptians, highlighting their refined artistic sensibility and technical skill,” he says.

Vandenbeusch, whose specialty is in funerary archaeology – she works with CT scans of mummified remains in order to decipher how the ancients were prepared for the afterlife – understands better than most the global appetite for ancient Egypt. So what is it that so attracts us?

“I think it’s a combination of things,” she says.

“The first one is that it’s all quite grand. I mean, you have the pyramids, you have big sculptures. But for me, that’s just one part of the story, because you have that in other places – other civilisations, too.

“The preservation in Egypt is key: the local climate is very dry, and it really allowed time to preserve a range of objects that you have nowhere else for that time period. It is quite extraordinary. And it is an incredible way for us to learn about ourselves.”

Australians’ love affair, en masse, began 40 years ago. The most successful ancient Egypt show staged here – also called Gold of the Pharaohs – was held in various cities around the country in 1988, and saw a million visitors over its 10-month run. The show, staged by the organisation now known as Art Exhibitions Australia, was like nothing the country had seen.

As Sydney-based art critic John McDonald wrote on his blog earlier this year, Gold of the Pharaohs’ 1988 visitor figures represented a phenomenal 6 per cent of the population. An aggregated approximation of that number would be 1.6 million in today’s terms, he deduced. It’s unlikely that 1988 show will be beaten any time soon – though it’s a fair bet the proposition will have crossed the ever-ambitious Ellwood’s mind.

It’s 11am, and the lines for the British Museum are still snaking down Great Russell St, past the overpriced antique coin dealers and cheap merchandise stores selling mugs and aprons emblazoned with a crown and text that reads “Long Live the Queue”.

Vandenbeusch leads Review through a door of the collections room, and down an ageing, narrow staircase. She pulls open a door, and we are, almost magically, transplanted on to the ground floor of the museum. There must be thousands here already, and Vandenbeusch takes no prisoners as she swerves her way through the throng. She’s done this before. “I’ve worked here for 11 years,” she calls out with a smile. As we approach the Ancient Egypt galleries, the curator points up towards an space where, until a week previous, had stood a 269cm-tall stone statue of Amenhotep I, who ruled during the 18th dynasty.

“It’s in conservation,” she says. “But I am so excited about it. It’s been in the sculpture gallery for ages – a generation at least – with its back towards the wall. And the other day I went to conservation and I discovered, well I rediscovered, that there is actually a column of hieroglyphs at the back, which had not been properly documented or photographed.

“Of course I’m not saying I’m the first one to see that. Not at all. But my point is that even with objects that we think we know very well, we can always see them in a new light.”

The statue came from a mastaba, the upper part of a tomb – akin to a highly decorated chapel – where mourners would pay their respects. (The lower part of the tomb was the burial chamber.)

We move among the crowds en route to the Enlightenment Galleries to see the Rosetta stone, that great, controversial chunk of granodiorite carved during the Hellenic period that became the key to unlocking the secrets of ancient language. Naturally, the stone – a trilingual text in hieroglyphs, Demotic and Ancient Greek – will not be leaving the museum for Australia, let alone for Egypt. Indeed, it has not left the museum since Britain procured the stone from the French under the terms of the capitulation of Alexandria in the early years of the 19th century. It had been discovered just years earlier in Rashid (Rosetta) by French officer Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.

The Rosetta Stone remains the most visited exhibit in the British Museum’s collection, and one of the most contentious. Recent years have seen energised petitions for the return to Egypt of the stone, the ownership of which by Britain has been variously called a “symbol of Western cultural violence” and “an act of plunder” by leading Egyptian scholars. The museum, for its part, has said the Egyptian government has never made a formal request for its return.

The BM, also home to the Parthenon’s Elgin marbles, is evidently no stranger to controversy over international objects of cultural significance. And while Vandenbeusch won’t be drawn on the issue of repatriations, she says the act of collecting at the institution, and around the world, has changed.

“There are still some acquisitions made, but it’s not the main focus, at least for Egypt and Sudan departments,” she says. “What we’re really trying to do is to develop partnerships and the exchange of skills and knowledge with Egypt and Sudan.”

Like a pair of upstreaming salmon, we flit through a throng of weekday pensioners and schoolchildren and arrive at a stunning representation of Amenhotep III portrayed as a lion, a recumbent vision of beauty and power in red granite that sits sentinel in the centre of the galleries. It stares at a mirror image of itself on the opposite side of the floor space. Cartouches – the oval emblem containing royal names – at one of the animal’s paws reveal the title of Kushite ruler Amanislo, as well as featuring the remnant of Tutankhamun’s name, which at some point after his death has been erased (it is still possible to see “amun” and “ankh”, Vandenbeusch says). Before Review has a chance to remark on the granite’s impossibly smooth surface, a visitor puts his hands on the lion’s back, and then stretches out across the 1390-1352BC monument.

Vandenbeusch makes a beeline. “Excuse me, no touching!” she says, politely but firmly.

The curator smiles as we walk around the statue. “I am sorry. I can’t help myself,” she says. “They’re quite beautiful, tactile objects, of course. But the more people touch them, the more they need to be cleaned and cared for. We want to keep them on display. We do not want to put everything behind glass.”

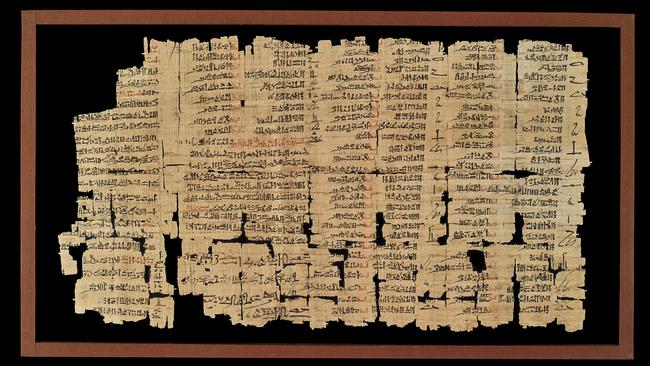

Back in the collections room, Vandenbeusch relieves the table of two large adjoined panes of glass. Between them is a 3000-year-old sheet of papyrus, its slightly torn edges doing little to betray its remarkable condition.

Roughly, 35cm long and 30cm tall, the parchment – the Papyrus Chester Beatty III – is emblazoned in Hieratic, the cursive writing system that endured from the third millennium until the rise around 1000BC of the Demotic system of writing.

“This is dream book,” says Vandenbeusch, reading from the fourth of four sections of papyrus. “It belongs to the archive of a family of scribes, about whom we know a great deal. They were also from Deir el-Medina.”

She pulls the text close to her face, and, at Review’s prompting, translates the document, written by an unknown author.

“If a man sees himself in a dream drinking blood, then this is a bad (omen),” she reads. “It means that the person will have a fight in the near future.”

The curator points to large swathes of red text. “Things written in red are meant to signal danger,” she adds, “to make sure that the person reading is aware that they need to be careful.”

Vandenbeusch turns over the parchment, with a smile: “But I also really love this side …”

Scrawled on the document’s obverse is a veritable jungle of symbols, a Hieratic retelling by a scribe named Qenherkhepshef of the Battle of Kardesh, the defining war of Ramses II’s reign.

“The author has taken this document and copied the story on the back. It’s a poem about that battle, which would have happened not long before the man who wrote it lived (in the 13th century BC).”

As ever, Vandenbeusch finds the human – and the humour – in the historic. “We can tell exactly who this man is because of his handwriting. I mean look at it,” she says with a laugh. “It’s quite horrendous. But I think it brings us back. It’s quite nice to show people of that time through that kind of human lens.”

Vandenbeusch moves back over to those two pharaohs in miniature; they waited for millennia in darkness, and they wait still in the dappled light of this collections room. The curator carefully sweeps up the statue of Senwosret III and holds it with all the care of a new mother:

“Egyptian statues, especially for great kings, are all very highly curated. They selected what they wanted to show up to translate to their people and to history,” she says.

“I can’t wait for people (in Australia) to see this. Unlike most Egyptian kings, which are completely idolised, you have the feeling Senwosret III wanted to be portrayed in a naturalistic sense. He was different. See his tired features – they show that he is wise. And, see the size of his ears – they’re unnaturally large. That is to show that he’s listening. Always listening. Always interested.”

Is there a lesson there for all of us, Dr Vandenbeusch?

“Well, yes. The truth is there is so much for us yet to know. And quite a lot still to discover. If you look in the newspapers, every few months there is a massive new discovery (regarding ancient Egypt),” she says. “But perhaps more importantly, there is a lot – still so much – to learn from the things that have been already discovered.”

Pharaohopens at the National Gallery of Victoria on June 14 and runs until October 6. The writer travelled with the assistance of the National Gallery of Victoria.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout