Tom Wolfe’s novel, A Man in Full has been brought to life in a lavish new TV series

Tom Wolfe’s 1988 laceration of male pomposity, A Man in Full, resonates with relevance, splendidly brought to life in David E. Kelley’s lavish new TV series.

You might just remember Tom Wolfe, that literary celebrity in the final decades of the last century, the American novelist, journalist, and social commentator. His books include The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, The Right Stuff and Bonfire of the Vanities.

If that wasn’t enough, a prolific and much envied journalist, he was also a major exponent of what was known as New Journalism, along with Jimmy Breslin, Gay Talese, Hunter Thompson, Joan Didion and others. Most were represented in The New Journalism in 1973, an anthology he edited with E. W. Johnson.

Wolfe wrote that, to him, the term “meant writing nonfiction, from newspaper stories to books, using basic reporting to gather the material but techniques ordinarily associated with fiction, such as scene-by-scene construction, to narrate it.”

His journalism also made him famous, and envied. The New York Times said in its obituary – Wolfe died in 2018 at the age of 88 – that he was a writer, “who found delight in lacerating the pretentiousness of others. He had a pitiless eye and a penchant for spotting trends and then giving them names, some of which – like ‘Radical Chic’ and ‘the Me Decade’ – became American idioms.”

The obituary writers added that, “His talent as a writer and caricaturist was evident from the start in his verbal pyrotechnics and perfect mimicry of speech patterns, his meticulous reporting, and his creative use of pop language and explosive punctuation.”

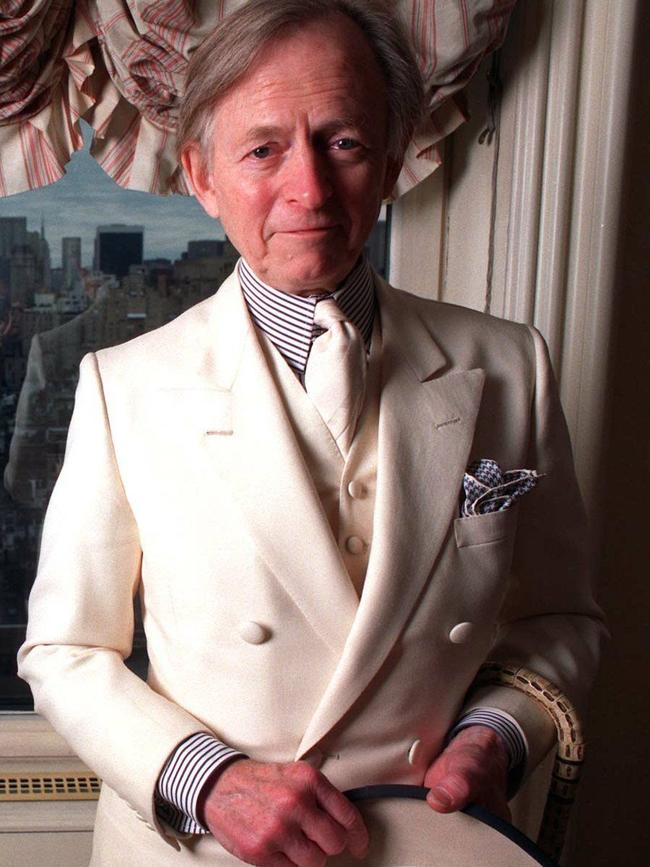

His apparel was as celebrated as his innovative grammar, Wolfe favouring spotless three-piece vanilla bespoke suits, pinstriped silk shirt with a starched white high collar, and white shoes.

He called the style “Neo-pretentious”. He was often called “The Man in the White Suit” in gossip columns.

His novels were bestsellers, some made into successful movies, and one of them, A Man in Full, has now been reimagined by the seemingly indefatigable Big Little Lies creator David E. Kelley into a lavish Netflix TV series.

He’s both the writer and the showrunner; the impressive Regina King is the originating director, having won critical acclaim for her feature debut, One Night in Miami; and the final episodes are directed by Thomas Schlamme, best known for his work on Aaron Sorkin’s The West Wing. The versatile Jeff Daniels stars alongside Diane Lane, Lucy Liu and William Jackson Harper.

There’s also a mesmerising performance from Tom Pelphrey, best known for his Citizen Kane co-writer Herman Mankiewicz in David Fincher’s Mank.

Daniels is pretty darn formidable too. As he usually is. I can still recall just how good Daniels was in Sorkin’s The Newsroom – handling the writer’s characteristic long monologues with rare skill – playing a middle-aged TV anchor who experiences a sudden epiphany, after which he decides to break only credible news in the world of US cable TV, dominated by celebrity gossip and fluffy, ratings-driven beat-ups.

A Man in Full, published in 1988, a sprawling doorstop of a novel at over 700 pages that excited critics as much as it famously dismayed writers John Updike, Norman Mailer and John Irving. Mailer said that “reading the work can even be said to resemble the act of making love to a three-hundred-pound woman”, adding, “Once she gets on top, it’s all over. Fall in love or be asphyxiated”; Updike said that it wasn’t “literature, even literature in modest aspirant form”; and Irving said, “It makes you wince”.

Wolfe, the great champion of social realism hit back.

“All three have seen the writing on the wall,” he said, “and it reads: A Man in Full.”

The critics loved it. The New York Times praised Wolfe’s audacity to attempt “the stuffing of the whole of contemporary America into a single, great, sprawling comic work of art”.

Publishers Weekly called it a dazzling performance “offering a panoramic vision of America at the end of the 20th century that ranges with deceptive ease over our economic, political and racial hang-ups”.

Its critic compared Wolfe to Balzac and the eminent Martin Amis said, “He forces you to compare him with his beloved Dickens.” At the time it sold just on a million and a half copies, Wolfe receiving an advance of $US7.5m. Kelley told the Netflix web site Tudum that it wasn’t difficult to modernise the story, aided, he said, by Wolfe’s prescience. “He could see things as they were and as they were going to continue to be. The themes, whether it be racial and class disparities, the vanity of man, or the criteria that mankind seems to use to take measure of themselves, were as ripe as ever.” He added, “Beware the male ego; if it’s not checked, it’s capable of all kinds of havoc.”

The drama is centred on Daniel’s wonderfully exaggerated Charlie Croker, an exemplar of overblown Southern manhood, his working philosophy: “Never justify, never explain, and never back off.”

He’s a bull of a man with a stentorian voice and an at times incomprehensible accent, a megalomaniacal white real estate developer, known as “The Man Who Built Atlanta”.

Trouble is, his empire, along with his identity, is hurtling toward bankruptcy. The huge ego is suddenly confronted by reality. (The title it seems refers to Croker’s idea of himself as a model of manliness, aggressive and dangerous. Described by Wolfe, he has, “The power to charm men and the manic drive to bend their wills into saying yes to projects they didn’t want, didn’t need, and never thought about before.”)

Kelley begins the Croker show – the first episode titled Saddlebags, a caustic reference soon explained – with a bizarre voice-over monologue from the Atlanta real estate mogul, the camera circling above his body prostrate on the floor. “I don’t mean this as a criticism, maybe I do, but when you die will people notice?” he asks. “When I do there are going to be a lot of memories of me by a lot of people who hate me even so. A person needs to live with vigour, otherwise what’s the point? At the end of the day a man’s got to shake his balls.”

We flash back 10 days to a lavish party celebrating Croker’s 60th birthday full of the corporate elite and their trophy wives serenaded by Shania Twain.

And we’re introduced to Pelphrey’s creepy Raymond Peepgrass, some kind of banker intimately involved in Croker’s financial life who loathes him – “He treats me like his butler,” he says – and is joyfully plotting against him.

He takes a call from Harry Zale, head of Croker’s bank’s Estate Management Division, played brilliantly by Bill Camp, who wants intel on Croker before a meeting scheduled for the next day. Peepgrass tells him how the real estate mogul bungs on the southern accent as he gets nervous and sweats through his shirts, blotches that look like saddlebags. “That’s when you know you’ve got him.”

When they meet the next day at the bank Croker is ambushed. He thinks he’s merely there to discuss some refinancing arrangements. “Think of this as an AA meeting, Mr Croker,” Zale tells him. “Now that the spree is over, we want to see some real self-awareness.”

It turns out Charlie Croker owes the bank $800 million and hasn’t paid back a cent, not even the interest. What’s more he owes six other banks another 400 million. He’s well over a billion dollars in debt.

The major sub plot – there a number – involves Croker’s receptionist Jill Hensley (Chanté Adams) and her husband Conrad (Jon Michael Hill). They are black, and suddenly, through no real fault of his own, Conrad becomes caught up in a police brutality case. It’s a situation that will involve Croker’s personal lawyer Roger White (Aml Ameen), who is also black, already hesitant about his role.

Meanwhile, the sneaky Peepgrass has problems of his own facing crippling alimony proceedings, forced to live like a pauper, inexpertly microwaving his meals.

American critics were somewhat tepid in their reviews, but I enjoyed the propulsive style of King’s direction and Kelley’s witty adaptation. It’s enjoyable and a lot shorter that having to read more than 700 pages. And the acting is splendid. Daniels even manages to find some humanity in the imperious, sweating Croker.

“The trick is to go that big, that larger than life, and still be believable,” the actor told Indiewire. “You don’t want to be winking at the camera, going, ‘I’m really just goofing around here.’ You want to portray this guy and it’s an exaggeration, fiction, and a TV show, but you want it to be plausible.”–

And Bill Camp pulls out all the stops too. “I am talking to a shithead about one of the worst cases of mismanagement I’ve ever seen,” he snarls in the terrific boardroom scene in which he ensnares Croker.

It’s all rather timely, as that other larger than life man in full, the narcissistic New York property tycoon, is also facing his own reckoning.

A Man In Full streaming on Netflix

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout