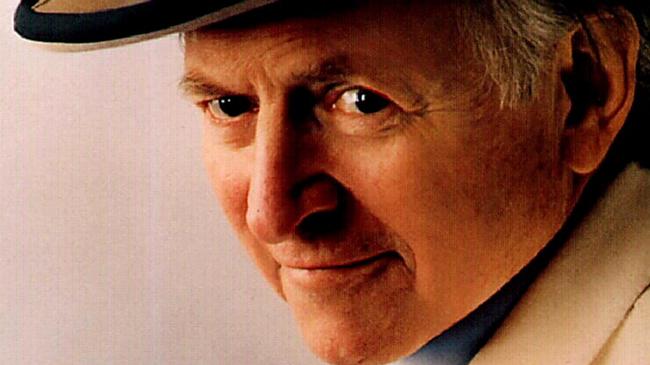

Tom Wolfe: New Journalism’s roaring lion

American writer and journalist Tom Wolfe, who has died in Manhattan, aged 88, was to the Age of Aquarius what F. Scott Fitzgerald was to the Roaring Twenties.

Tom Wolfe was to the Age of Aquarius what F. Scott Fitzgerald was to the Roaring Twenties. A pioneer of America’s “New Journalism”, he brought a vigorous, slangy yet sceptical eye to the cultural trends of the 1960s. He was an equally shrewd observer of the 70s, an era he christened the “me decade”. Having championed the merits of reportage over contemporary fiction, he finally turned to the novel in mid-life, scoring huge success with The Bonfire of the Vanities, a bustling satire on New York’s social and racial divide.

In his trademark white suit, spats and fob watch, Wolfe cut a dandyish figure in the grimy streets of his adopted home, Manhattan. Although his articles and books placed him at the heart of the counterculture — he mingled with hippies, artists, socialites and Hells Angels — his nonconformism had a conservative streak that surfaced most clearly of all in his 1970 essay Radical Chic.

If there was one group that did win Wolfe’s unconditional admiration, it was the crew-cut test pilots portrayed in The Right Stuff (1979). In this colourful history of the Mercury space program he relied less on his usual pyrotechnics than on hard journalistic graft.

He had started work on the now-defunct New York Herald Tribune in 1962. To Wolfe, New York was “pandemonium with a big grin”. Renowned columnist Jimmy Breslin was already making a mark on the Tribune as a laconic observer of blue-collar life. From him Wolfe learned the importance of gathering first-hand material and the value of vivid novelistic detail.

In place of the understated prose of conventional journalism — “that pale beige tone”, as he put it — he developed a snappier, phantasmagorical style that reflected the hectic patterns of everyday speech and the vitality of the generation coming of age in the post-Kennedy era. In articles for the Tribune’s colour supplement, Wolfe bent grammar and punctuation to his own purposes.

Exclamation marks ran riot and his streams-of-consciousness rang with the thunder of his typewriter keys. (Even in the 90s he stayed loyal to old technology.) His aim, as he later explained, was to write “journalism that read like a novel”.

Although usually thought of as a quintessential New Yorker, his roots lay in the aristocratic south. Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr, the grandson of a Confederate soldier, was born into an old Virginian family in Richmond. His father, Thomas Kennerly Sr, was an agronomist, teacher and businessman, while his mother, Helen, was a landscape designer. She infused him with a love of art and reading that would remain with him.

The young Tom attended a private boys school in Richmond. At the age of nine he tried to write a biography of Napoleon. “I also did a comic book: the complete story of Mozart’s life. The reason I liked them then was that they were both small; when I was nine I too was small. Napoleon seemed like a child who had conquered the world, and Mozart was only 10 or 11 when he gave his first concert. There’s great virtue in having an early vocation.” He later studied at the traditionalist Washington and Lee University, graduating with a degree in English in 1951 before embarking on graduate studies at Yale, where he earned a PhD in American studies. He was also a decent baseball pitcher — so good that he had a trial with the then New York Giants (now the San Francisco Giants).

Compelled by what he described as “an overwhelming urge to join ‘the real world’ ”, he embarked on a career in journalism. After spells on the Springfield Union and The Washington Post, he landed in Manhattan.

A visit to a hot-rod car show sparked his interest in the way America’s tastes were being shaped by “the proles, peasants and petty burghers”. Dispatched to California by Esquire, Wolfe wrote up his experiences among the car enthusiasts in the essay that gave its name in 1965 to his first collection of essays, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. Whether describing a visit to Las Vegas or the new-born rituals of the rock concert, Wolfe’s theatrical style caught the spirit of the age. In 1968 The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test was a snapshot of the LSD-fuelled bus odyssey undertaken by novelist Ken Kesey and his coterie of “Merry Pranksters”. Wolfe, perhaps surprisingly, never took LSD himself. “I probably have given that impression in the past, but I didn’t,” he said in 2016.

As the optimism of the 60s began to curdle, Wolfe caught the changing mood in Radical Chic (1970), which first appeared when an entire issue of New York magazine was dedicated to “These Radical Chic Evenings”, Wolfe’s 20,000-word satire of the fundraising evening given for the Black Panthers by Leonard Bernstein, conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and his wife, Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre, in their Park Avenue penthouse.

“Do Panthers like little roquefort cheese morsels rolled on crushed nuts this way, and asparagus tips in mayonnaise dabs, and meatballs petites au Coq Hardi, all of which are at the very moment being offered to them on gadrooned silver platters by maids in black uniforms with hand-ironed white aprons?” Wolfe wrote, outraging liberals and Panthers alike.

Wolfe’s pre-eminence was underlined by his editorship, along with writer EW Johnson, of the anthology The New Journalism (1973), which featured work by, among others, Michael Herr, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer and Joan Didion.

At the same time he struggled to settle in his private life, observing that New York was not a propitious city for marriage. This changed in 1978 when, aged 47, he married Sheila Berger, who was art director at Harper’s magazine. They had two children: Thomas, who is a furniture designer and sculptor; and Alexandra, a writer on The Wall Street Journal who last year wrote Valley of the Gods: A Silicon Valley Story.

He savaged novelists whom he regarded as overrated; Saul Bellow was a regular target. In the polemics The Painted Word (1975) and From Bauhaus to Our House (1981) he ridiculed modernist trends in art and architecture, arguing that they had led to the triumph of theory over practice. Using the broadest of brushstrokes, his attacks made up in brio what they sometimes lacked in detail.

However, his targets were wont to fight back, especially Mailer, who remarked in 1989: “There is something silly about a man who wears a white suit all the time, especially in New York.” Wolfe responded vigorously: “The lead dog is the one they always try to bite in the ass.” And Mailer matched him: “It doesn’t mean you’re the top dog just because your ass is bleeding.”

Asked about the British in 1980, Wolfe said he could not write about England because it took him a fortnight to get to know the language and work out whether he had been insulted. Five years later he tackled the subject. Split between an acute appreciation of snobbery and a republican desire to put England in its place, his view of the British was ambiguous.

In 1987 came his long-awaited first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, which was intended to bolster out his claim that the future belonged to the so-called “documentary novel”. This semi-comic morality tale, with a title inspired by Girolamo Savonarola, first appeared in serial form in Rolling Stone. After a long period of revision, Wolfe changed his central character from a writer to a complacent young Wall Street bond trader and self-styled “master of the universe”.

Wolfe drew closely from life. The rabble-rousing preacher, the reverend Reginald Bacon, for example, was modelled on Al Sharpton. With its scrupulous detailing of brand names and society conventions, The Bonfire of the Vanities held up a mirror to the New York of the 80s.

Bonfire’s detractors, led by novelist John Updike, argued that the book belonged in the category of entertainment rather than literature. Whatever its merits, Bonfire proved an enormous bestseller, although Brian De Palma’s film adaptation starring Tom Hanks as Sherman McCoy was a critical and commercial disaster.

Flushed with his literary success, Wolfe published what amounted to a manifesto in Harper’s magazine. Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast argued that writers had a duty to engage with the workings of the society surrounding them. By comparing himself to Emile Zola and Charles Dickens and dismissing many of his contemporaries, Wolfe provoked enormous controversy.

Every day he set a target of writing 10 pages, with triple spacing. If this was completed within three hours he would stop work for the day. “If it takes me 12 hours, that’s too bad, I’ve got to do it,” he said in 1991.

While at the gym in 1996 he suffered a heart attack and required a quintuple bypass operation. He also was treated for depression. The next year he took the unusual step of publishing a novella, Ambush at Fort Bragg, on audiocassette. A satire on media values, the work was written as part of a longer novel, A Man in Full, which appeared in 1998.

A Man in Full moved away from Wolfe’s usual stamping ground and focused on the simmering economic and racial tensions in contemporary Atlanta, beacon of the “New South”. Wolfe had no trouble in scaling the bestseller lists once more, but the book led to a ferocious feud with his fellow literary heavyweights, Updike, Mailer and John Irving.

For Mailer, reading the 742-page doorstopper was comparable to “the act of making love to a 300lb woman … once she gets on top, it’s all over. Fall in love, or be asphyxiated.” Wolfe, he said, “may be the hardest-working show-off the literary world has ever owned … he lives in the King Kong Kingdom of the mega-bestsellers.” For Irving, Wolfe’s work was “pompous, puerile and laughable”.

The returns on his books continued to diminish, but in 2002 he received a National Humanities Medal from president George W. Bush. His third novel, I Am Charlotte Simmons, appeared in 2004, a campus novel about sex and social status. Back to Blood (2012), set in Miami and dealing with Cuban immigrants, fared equally badly, selling 62,000 copies in its first year, a poor return on the $US7 million advance paid by the publishers.

Away from his writing desk Wolfe continued to cultivate his artistic talent. His pen and ink drawings occasionally embellished his work, and he was a contributing artist at Harper’s in the late 70s and early 80s as well as exhibiting at Manhattan galleries.

Perhaps his greatest creation was himself, parading through the streets of Manhattan in what The New York Times described as “attire as satire”, which he called “a harmless form of aggression”. Once, asked to describe his clothes, the man who had at least 40 white suits replied: “Neo-pretentious.”

Tom Wolfe. Writer and journalist. Born Richmond, Virginia, March 2, 1930. Died Manhattan, May 14, 2018, aged 88.

The Times