Tim Winton’s Juice: apocalypse now before it’s gone forever

If Tim Winton’s first novel concerned with climate change, 2013’s Eyrie, was a secular gospel – an account of redemption in a fallen world – then this is the Book of Revelation.

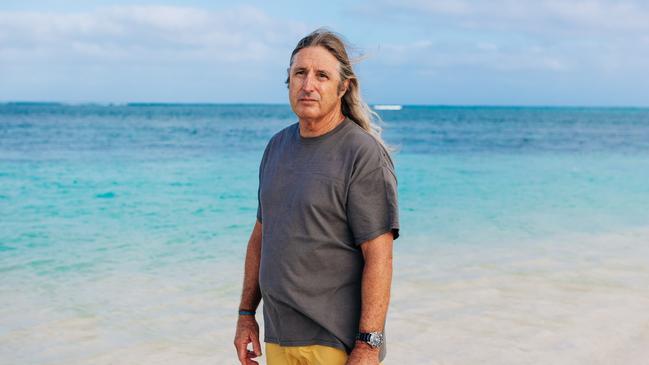

There has always been something of the lay preacher about Tim Winton: a sense that his stories are not told simply for diversion but are also intended to upbraid and galvanise. They should count for something in the world. Through a dozen novels, published across more than four decades, he has polished his fictional homiletics until they are equal parts brimstone and treacle.

If his first novel concerned with climate change, 2013’s Eyrie, was a secular gospel – an account of redemption in a fallen world – then Juice is the Book of Revelation. It describes an apocalypse, a great and terrible unveiling. Its narrative explores the thunderous finale to our modern eschatology, built as it has been on the promise of limitless growth allowed by the juice of the title: fossil fuels.

The novel opens in medias res, many human generations in the future, in the West Australian outback. A worn, older man travelling with a mute girl is captured by another man, who has taken over a former underground mine as his redoubt against a society that seems to have entered its final days.

The plains of this country are thick with ash. Birds and trees are rarities. The weather, challenging for years now, has turned impossible. Those people who are left are mobile and hungry. In a framing device straight out of a Joseph Conrad novel, the older man relays his life story in fits and bursts to the suspicious, armed other over the course of a night. He does not talk to save his own life, we come to understand, but to save the child who does not belong to him.

An old-fashioned way to tell a futuristic story, this, and it may take readers time to settle in. But this is a Winton novel: every machine-tooled sentence is its own reward. And once the story clarifies, the sheer length of the novel becomes its greatest pleasure rather than unwanted graft.

The narrator, we learn, has lived a life divided between bucolic remove and sanctioned violence. His home was, for decades, on the plains towards the state’s north. This was marginal country, weather-wise, but relatively peaceful for those who could make a life there.

Winton’s world-building has a detail and expansiveness that is frighteningly plausible. This is a planet altered, irrevocably, by climate change and the collapse it caused to complex societies of our present. The narrator is part of a community who live by agricultural subsistence and local trade, whose tech consists of all terrain rovers, solar panels and turbines, but little more. The internet is an old rumour, and culture is based on “sagas” built from a melange of poetry, the Bible, and folk memory.

The area’s weather remains monsoonal, albeit supercharged and erratic. The weather can be fatal. Winters are spent in a frantic provisioning of water and food. Summers are spent hibernating below ground.

The narrator, who lives with his tough-as-boots mother, nonetheless loves this country. He grows into knowledge of its deeper human history at the same time he gains competence with those protocols of survival which sustain them in the present. Yet there are aspects of his society which remain opaque: until, that is, the narrator is recruited, as a young man, into a secret militia force.

The hardest sell of Juice comes with those parts of the book narrating the man’s second life as a trained killer. Because Winton imagines a world in which those super-rich beneficiaries of the fossil fuel era – the ones currently building their multi-storey bunkers in New Zealand and Patagonia – remain a force in the world. The distant offspring of these “criminal clans” are the targets of the narrator’s militia. Theirs is a roving Nuremberg tribunal summarily raised against those who profited from the end of the world.

The moral force of the argument Winton mounts gains clarity from the perspective of a future in which the worst effects of our current selfishness and greed have manifested. However, the author is also at pains to register how even the most righteous vengeance can be corrupted. The narrator’s journey is from a boyish sense of the glamour of violence, to a maturity of profound disenchantment with the cause: one, we learn, has cost him and his family almost everything of real worth.

Back in the narrative’s present, the captor is mistrustful of our man’s account. He, too, has been a militia member; he has his own version of events. And he evinces a loathing for the robots, “sims” as they are called, who our narrator has come to respect over the course of his work.

Winton drives Juice towards its conclusion with a narrative force that feels almost cyclonic. It’s a thrilling account, but also terrifying in implication. The man and his young ward appear just two more people set to be swept away by events. That the novel should, nonetheless, end delicately poised between potential futures allows the reader blessed, unexpected respite. The author wants us to consider all that has been lost, and what still might be saved, in the stillness of the storm’s eye.

Geordie Williamson has been chief literary critic of The Australian since 2008.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout