Poets WB Yeats, Simon West and matters of style

On questions of style, there are two types of poets. Those who stick with their style, and those who throw it away

On questions of style, there are two types of poets: those who establish a distinctive one early and maintain it, with adjustments, throughout their oeuvre, and those who pass through discrete changes, sloughing off old habits for new.

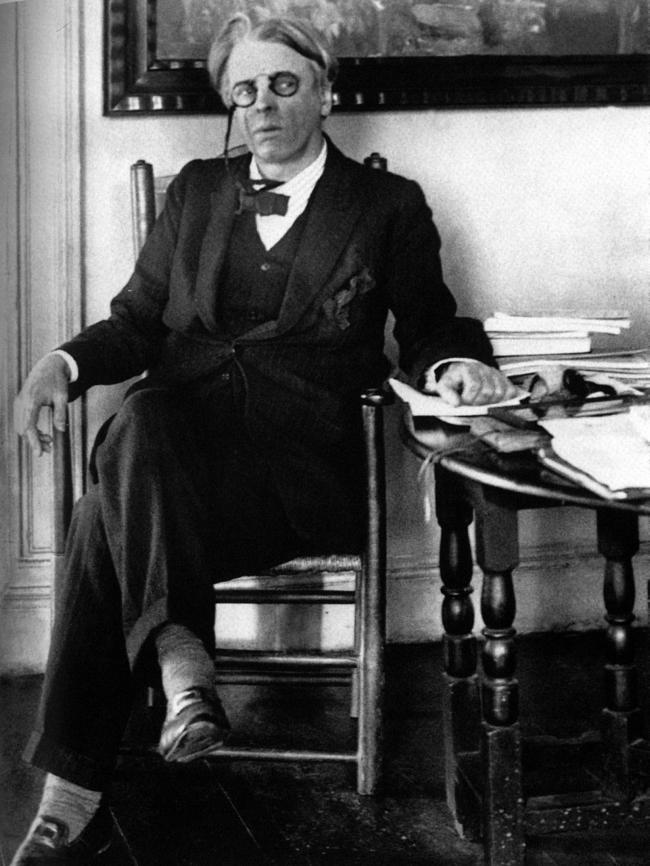

WB Yeats, who began with a dense, incantatory romantic style but later abandoned it for a more direct, conversational one, belongs to the latter camp. He even wrote a poem about this shift, likening it to sloughing off a coat:

“I made my song a coat / Covered with embroideries / Out of old mythologies”, he wrote, lightly mocking the esotericism of his early poems, and concluding in favour of simplicity: “there’s more enterprise / in walking naked”.

The most recent collection by this week’s poet, Simon West, is interesting because it seems to signal a shift in the style that characterises his previous collections. West, a translator and Italianist, has lived for significant spells in Turin and Rome. He also has translated the work of Dante’s contemporary, medieval Italian poet and troubadour Guido Cavalcanti.

His first three books bear a strong Italian stylistic influence and focus on Italian and Australian landscapes. This snippet from his poem A Valley gives a sense of his early style: “Fog dawns. / Under the gum / red stamens, frigid bees. / What would have been. / What will come again.”

In his fourth collection, Carol and Ahoy (Puncher & Wattmann), West continues his focus on landscape — mostly eschewing Italy for the Goulburn River and the flood plains around Shepparton — but opts for a longer, denser line, with the intermittent use of rhyme and a more baroque vocabulary. It’s possible this longer line length lends West a looseness that he has not allowed himself in earlier books. These poems seem more discursive and pensive, opening up into longer reflections.

The collection opens with River Tracks, a poem addressed to the Goulburn River which, the poet tells us, is “never a straight line or a single course”. He proceeds to reel off its shifting names, which track its colonial history, suggesting that history, like the river itself, is full of flexure and change: “Round Murchison it’s said the Ngooraialum / called you Bayungun, but Mitchell / might have got this wrong. Waaring / was also recorded, while downstream you were Kialla / and Goopna, deep waterhole, / living on in Congupna and Tallygaroopna.”

The poet rises out of this linguistic strata to view the river from an unorthodox vantage point — “from the up-high of satellite and migrating bird, / who know their course by impulse / you’re as unkempt as a camper’s hair” — before returning to the ground, where “long-suffering red gums” await the river’s “next incursion and siege” when it floods. He closes with an image of the river rising and spreading like a “salve” over paddocks and properties, “letting us bide for a bit in common reflection”, which suggests the mirroring of the water but also the thought processes involved in apprehending it.

It’s a sophisticated poem that signals West’s intention for the collection: to unearth the layered history of the landscapes, but also to examine the act of apprehension itself, and how language is imbricated in the act of seeing and observing. Throughout Carol and Ahoy, West is explicit about the redemptive qualities of naming and describing. The title comes from the poet’s description of a blackbird’s carolling, and suggests poetry’s dual functions as song and message.

The poem Back at the Broken River ends with lines that might serve as a declaration of intent. “Pausing / to give each cherished thing its name / I find / a poise that redeems my distance from the world.” But as he names the landscape, West also transforms it through his powerful image-making: the sun as a “raw morning bulb”, gum nuts as “bullet-hard”, gum trees standing “in their tender under-skins / streaked like boiled sweets”, and the reflection of sunlight on water as “scabs of light off Bass Strait”.

This transfiguration of the landscape moves beyond the simple act of naming through the alchemy of metaphor, fulfilling the poet’s dictum in Uncanny Nature: “What a poem distils it must also set free.” I suspect this line may serve as a kind of road map for the shift that has taken place in West’s poetics: a poetry that is exacting but also liberated and expansive in its gaze.

At the core of Carol and Ahoy is a set of poems about the Goulburn River and its colonial history, including one about the poet’s own convict ancestry in Tasmania, a “house whose memory is stunted like the broken bole of a tree”.

There are also poems about the flora and fauna of the region, including the bacchanalian feasting of lorikeets in a flowering gum that leaves the ground “strewn with little round caps / like a rout of shields after an Athenian battle”. Such references to the classics abound, including a translated passage of Virgil’s The Aeneid, in which Aeneas seeks the golden bough that will admit him to the underworld so he can visit his father.

West’s translation is dedicated to his father, who died in 2015. This weekend, as it’s Father’s Day, I’ve chosen Swimming, West’s moving, subtle elegy for his father. In it, the poet takes a walk around a bay, escaping an “airless” house in which the poet has “haunted your not being there” — an inversion of the expected phrasing in which the living haunts the departed.

You’ll note the line lengths eddy from long to short as the poet walks, perhaps reflecting the shape of the landscape itself. As the poet walks, intermittent end rhymes enter and depart, lending the poem a sense of order but withholding the tidy sound of a regular rhyme scheme. As West shifts between the landscape in front of him and memories of his father, he perceives in the elements something “too vast, you’d say, for words”, a line that signals a shift into the poet’s reflection on language itself, and its inadequacies as he receives a visitation from his father in the form of a memory of him swimming.

“I thought of you / The thought bridged both your being / and not being, and made no sense.” Language, while vast, abuts something greater than it can fully encompass in the poet’s grief.

The poet’s compromise at the end is to accept this inadequacy as a kind of grace, which is also embodied in the landscape’s tide and “dipping birds”, as the poet nods to the trees — a kind of deference that one might show a father, now found in the figure of the tree that sustains so much of the life in this fine collection.

-

Swimming

Too neat for ghosts the borrowed house was airless as a scene from Ibsen.

I haunted your not being there and counted down as currawongs glibly heralded then mourned each day.

Late on the last wet afternoon, more restless than convivial, I walked towards the bay.

A clump of coastal pines, a blanket of needles where the cliff declines and the headland curls up to the beach.

Pitching forward I snatched at each branch across the stepless track.

Halfway down it turns west and falls to where the surfers launch off cramped black rocks.

I stuck to the thicket and leant against a trunk, whose roots I reckon would first have sunk into the earth about the time of your own father’s birth.

Tall trees and through the tessellated boles, the sea.

I have no memory of him, just a photo with no frame.

I’m sitting loosely on his knee.

You never spoke of him nor of his wife – I barely knew their names – as though the past were some grim sheet of ocean, fathomless and without life.

On beachside holidays, a sentinel with naked feet, you squinted at the waves, and smoothed the sand of flaws.

When I picture you with water I see you gloved and in a greenhouse administering each seedling its daily dose.

I stood and watched it clashing with the shore.

Elemental things – too vast, you’d say, for words, too, primal and unchanged.

The mass of half-beached kelp.

The wind the terns and oystercatchers ranged.

I’d never seen this place before. I wasn’t likely to return. And yet I felt a kind of deference.

I thought of you. The thought bridged both your being and not being, and made no sense.

Perhaps some recognition did take place.

Perhaps my vision of you out there swimming meant that something was restored.

I don’t know what or if I’d call it grace.

Why not say I watched the tide, the dipping birds, and felt a kind of peace?

And then I nodded to the trees and went.

— Simon West

-

Sarah Holland-Batt is a poet and associate professor at the school of creative practice at the Queensland University of Technology. Poet’s Voice receives sponsorship from The Copyright Agency and the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas. Holland-Batt can be contacted at sarah.hollandbatt@qut.edu.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout