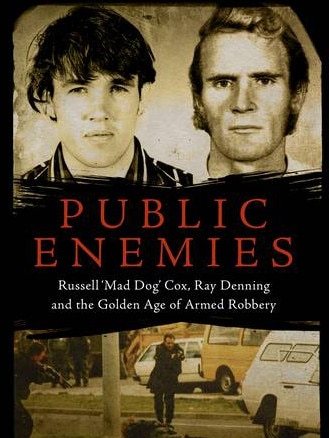

Claws reviews Mark Dapin’s new book Public Enemies

Russell “Mad Dog” Cox dangled from the exercise yard roof with one arm and used the other arm to hacksaw through a bar to escape from the high-security jail constructed within Long Bay.

Being inside a jail, mixing with inmates, is something I will never forget. I recall the day I decided never to commit a serious crime. We had just pulled up, in the ministerial car, at Grafton Correctional Centre. It was a grey day and rain was sheeting down. That was enough — but then we went inside. This phase in my working life is why I have a prevailing interest in the prison system.

Yet it goes back further than that, to my childhood, when my family lived down the road from Long Bay Correctional Centre in Sydney. My mother still lives there. I remember the days when police helicopters buzzed over the house and police officers filled the street. They were, as Dapin writes, making “the customary round of backyards and chook sheds” in pursuit of an escapee. I was almost 13 when Cox, then 28, did the impossible: he escaped from the “escape-proof” Katingal high-security jail constructed within Long Bay. This was the part I wanted to read first. In this book, a compelling mix of true crime, social history and social commentary, Dapin corrects the public record, a lot, and hints there are other bits of it that should be corrected. His take on the Sydney Hilton Hotel bombing in 1978 is interesting.

With Katingal, the futuristic “tomb for the living dead”, though, he basically accepts the story I grew up with: Cox, having exercised to build his strength, dangled from the exercise yard roof with one arm and used the other arm to hacksaw through a bar. It took a while but once that bar was bendable, he fled. That was November 1977. He was at large for 11 years. Early in this time — and this still defies belief — he broke back into Katingal to try to free some mates, then broke back out again.

Sydney-based Dapin is a journalist, screenwriter and author of works of fiction and nonfiction. The blurb for this book describes him as “popular and acclaimed”. On the opening page, he describes Cox and Denning as “popular men in prison: natural leaders, charismatic, likeable and tough”. As someone who has spent time in a boxing ring with Dapin, I can confirm that he is likeable.

Dapin interviewed crooks, cops and judges for this book, but not his leading men. Cox, released in 2004, is still with us, living in Queensland, where he was born Melville Peter Schnitzerling. Denning died in 1993, aged 42, of a heroin overdose that Dapin and many others believe was murder.

This book starts at the start, with the childhoods of the men who would become public enemies. Each was abandoned by his father, each spent time in brutal boys homes. “… prolonged exposure to violence,” Dapin writes, “offers lessons a boy can take away for the rest of his life”. Importantly, he does not offer this as an excuse. The risk in writing about daring criminals, I think, is to glamorise them, to Bonnie and Clyde them. Dapin does not do this.

Writing about Cox and cohorts robbing a hospital near Brisbane in late 1978, he observes: “They promise they will murder the workers in the pay office unless they hand over the Christmas pay earmarked for the honest and overworked doctors and nurses, cleaners, cooks and orderlies in a hospital. Our boys weren’t the Kelly Gang, that’s for sure. They weren’t Robin F..king Hood.”

Then he adds, in a characteristic note, “But then, neither were the Kelly Gang. Or Robin Hood.”

Like the hard men he writes about, Dapin does not pull punches. I know we have seen it all via Blue Murder and other TV shows and books about Sydney crime in the 70s and 80s, but it is still astounding to be taken back to the days, not so long ago, when the line between cops and robbers was, we now know, indistinguishable. Dapin lists politicians and senior police who now have this addendum: convicted criminal. Rogerson is doing a life sentence for murder, drug trafficking and perverting the course of justice.

The author jabs at the now-dead Mark “Chopper” Read, “who holds an unusual place in Australian criminal history as perhaps the only confessed multiple murderer who has never been accused — let alone convicted — of multiple murders”. He king-hits former corrective services minister Michael Yabsley. I love the scene in which senior detective Aarne Tees, fronting Independent Commission Against Corruption commissioner Ian Temby, resorts to an “epistemological” argument about Cox.

And if there is one Australian prison break more notorious than Cox’s, it is John Killick’s helicopter escape from Sydney’s Silverwater in 1999. That will be in the sequel Dapin is at work on now.

I can candidly say, without the need for a Roger Rogerson verbal, that I have spent time in most of NSW’s prisons. I was in them for professional reasons but not the same ones as Russell “Mad Dog” Cox and Raymond Denning, the main characters in Mark Dapin’s new book Public Enemies (Allen & Unwin, 368pp, $32.99). I was there as the media adviser to the NSW minister for justice. This was in the early 1990s, just after the timeline in Dapin’s book.