The true history of tantra: from Sankrit to sex ane beyond

Tantra arose from the collapse of a prosperous, peaceful and unified empire, in a time of disarray, violence and fear.

Religious experience can take very different forms, even within the same society and at the same time. In ancient Greece, for example, the official state religion was centred on the temples whose remains are visited to this day, and involved the worship of the Olympian gods with public sacrifices held outdoors, in daylight, in front of the colonnade and followed by a communal feast; but at the same time there were numerous so-called Mystery Religions or cults, most importantly those of Demeter and Dionysus, which originally offered plentiful harvests and material wellbeing but later promised blissful eternity in the underworld, instead of the drab and ghostlike afterlife of the uninitiated.

Christianity too, alongside the uniquely effective administrative structure of the Church, inherited from the Romans, and a uniquely coherent theology, shaped by Greek philosophy, had its heresies, mystical offshoots, wild hermits living in the desert, and countless whores and sinners who became great saints. But its art and architecture also reflect changes in religious sensibility in the course of time: consider the difference between the solidity and power of Romanesque architecture and the soaring lightness and space of Gothic; or between the rationality and symmetry of the Renaissance and the complexities and drama of Baroque buildings.

In painting, think of the gentle spirituality and piety of Fra Angelico in the 15th century compared to the violence and sensationalism of Caravaggio’s Judith and Holofernes painted around 1600. In fact I remember once being in a gallery in Milan, in a room full of decapitations (Holofernes, John the Baptist, Goliath) and gruesome martyrdoms at the same time as a group of bemused Japanese tourists; I wanted to tell them that our art is not all as lurid as this. It was something about the period just before and after 1600 – political instability, the rupture of Christendom with the Reformation and the outbreak of religious wars, new scientific ideas and theological quarrels about the path to salvation – a climate of ambient anxiety, that evoked these extreme images.

Something similar seems to have happened in India with the rise of the Tantra movement during a period of political instability and fragmentation about a millennium and a half ago. This was a vein of violent and ecstatic religiosity that arose within Hinduism but had a profound influence on Buddhism and on the practice of Yoga as well, and whose effect spread as far as China, Japan and Java, but especially and durably to Tibet, where it became the dominant variety of Buddhism.

Looking at this phenomenon in the widest historical perspective, the rise of Tantra seems to coincide approximately with a broader wave of neo-religiosity, and a corresponding decline in rationalism, across a wide area of the Eurasian continent. The 3rd century AD was the time that Christianity spread through and undermined the Roman Empire. It was also the time that Manicheism arose in Zoroastrian Iran, spreading into Christianity and as far east as China. The western empire fell to barbarian invasion in the 5th century, ironically leaving the Church as the only functioning institution capable of carrying on civilisation, and therefore greatly increasing its power. The eastern empire in Constantinople, meanwhile, became increasingly theocratic. In the 7th century Islam arose and rapidly spread through the conquest of Persia and large parts of the Byzantine empire.

In India, the Mauryan empire had been founded in the late 4th century BC by Chandradgupta Maurya, who is said to have seen Alexander the Great as a boy. He later established close relations with neighbouring Greco-Indian states, and his grandson Ashoka, the great patron of Buddhism, ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent.

After the Mauryans, the period from about 200BC to the Gupta Empire, which flourished from the 3rd to the 6th centuries AD and is usually considered the Golden Age of India, is called the Classical Period. After the fall of the Gupta Empire, partly as a consequence of barbarian invasions, India was again divided among small regional kingdoms, warring among each other, and the following period is known as Medieval: the early medieval period until about 1200, when Muslim invaders form the Delhi Sultanate, and the late medieval period from then until the Mughal conquest in the 16th century.

So Tantra arose from the collapse of a prosperous, peaceful and unified empire, in a time of disarray, violence and fear. It is not surprising that the religiosity that arose in this period was characterised by extremes and by paradoxical and unorthodox forms of behaviour.

Conventional religious practices must have been felt to be ineffective, even the originally unconventional forms of Hindu spirituality and Buddhism, which had by now become established and relatively conventional. There must have been a longing for more extreme and transgressive methods to achieve communion with the divine or attain enlightenment.

In the modern West, and especially since the countercultural movements of a half a century ago, the word Tantra almost always conjures up the idea of “tantric sex” as a sensual yet spiritual practice. A far more complete view of this complex subject is offered in the outstanding British Museum exhibition, which comes with an excellent catalogue and also with much interesting online material.

In fact as the museum is unfortunately closed at present because of COVID, Australian readers have exactly the same access to the exhibition as Londoners. The website has a concise outline of the story told at greater length in the catalogue, and has a couple of engaging video talks by the exhibition’s young but very knowledgeable curator Imma Ramos.

The Curator’s Corner video link will take you to YouTube, where you can also find the British Museum video on Tantra’s influence on Yoga, with Dr James Mallinson, one of the world’s pre-eminent Sanskrit scholars and co-author of the recent Roots of Yoga (Penguin, 2017), which brings together many hitherto unpublished and untranslated texts.

Anyone particularly interested in this topic should also look up the YouTube video on the Hatha Yoga Project, SOAS, University of London. In this video, you will see Mallinson still wearing dreadlocks (there can’t be very many Eton-educated baronets with dreadlocks who are leading Sanskrit scholars, initiated yogic ascetics and professors at the same time).

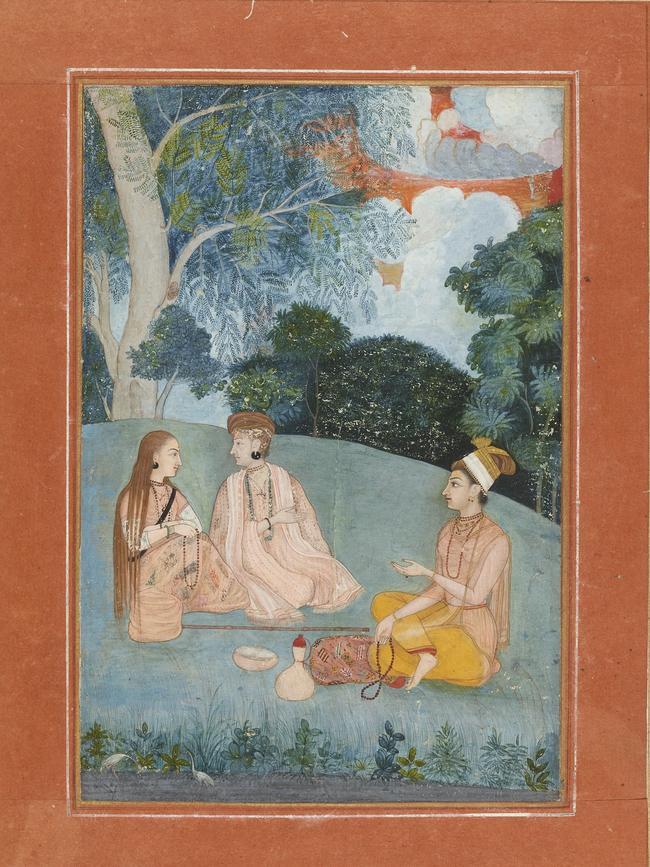

Tantra, then, seems to have arisen out of a crisis in religious faith brought about by social and political turmoil. If traditional social roles and ceremonies, hierarchies and ritual practices were not effective, paradoxically the very inversion of these might unleash new forms of power. So ascetics began to frequent unclean or polluting places, such as cremation grounds, and make ritual use of unclean and taboo substances, including urine, faeces, menstrual blood, sexual fluids or even human flesh. Perhaps it was this quest to invert all established norms and tap into the power of the taboo that led to the promotion of the idea of the feminine as the key to power.

In the earliest period, Tantric deities include Bhairava, a savage form of Shiva, and goddess figures based on the earlier mother-goddess Durga but much more terrifying, including one called Chamunda who is represented as semi-skeletal. There is nothing seductive about these female figures: they are bloodthirsty and murderous, adorned with decapitated heads and other symbols of death.

Their purpose, too, seems highly ambiguous. On the one hand they are imagined as the fierce and violent forces needed to overcome the ego and achieve liberation; on the other they are more akin to witches whose black magic can give rulers supernatural power in their military struggles with their rivals.

A couple of centuries later, the goddess figures become a little less terrifying, now in the guise of Yoginis, who are seductive as well as retaining savage and deadly characteristics. Their temples were circular, open and roofless, perhaps to allow the Yoginis to come down from the sky and commune with mortals. The communing was imagined as sexual but was of course dangerous as well; if the lover-devotee showed any fear, he would be devoured by the Yogini.

This idea of ritual sexual union became central to Tibetan Buddhism, and readers have probably often seen Tantric Buddhist sculptures from Tibet which represent a couple, often with many flailing arms, joined in sexual ecstasy. They are a male divinity called Chakrasamvara and the female Vajrayogini, and they are often shown trampling on two small figures identified as Bhairava and Chamunda – former symbols of Tantric liberation now treated as demonic obstacles to freedom. The two figures were of course meant to represent the quintessential masculine and feminine, united in the fusion of enlightenment, but within the Tantric system the male was associated with compassion, and the female with wisdom. It seems very likely that such sacred couplings were not confined to religious imagery but were also performed by male and female votaries of Tantra, giving rise to the modern idea of tantric sex.

One of the most important and enduring effects of Tantra was on the practice and theory of Yoga. In its origins, Yoga was a non-theistic practice aiming to achieve, in the words of Patanjali, the “stilling of the movement of the mind”, not unlike the Stoic quest for the calm and undisturbed mind. Centuries later, under the influence of Islam and Sufism, there was a tendency to think of Yoga as a way of achieving union with the divine, and we still hear teachers talk about both of these quite different aims, not always aware of their historical origins.

Meanwhile, Tantra transformed the physical, or asana practice. Early Yoga was chiefly concerned with meditation and breath control or pranayama; most of its asanas or postures were therefore seated ones, adopted for either of these practices. It was inspired by Tantra that Hatha Yoga adopted a wider variety of postures and movements, some of which had previously been used for ascetic practices. The full complement of modern asanas includes many more recent variations, and was codified by Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace between the wars, and popularised in the West by his pupils BKS Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois.

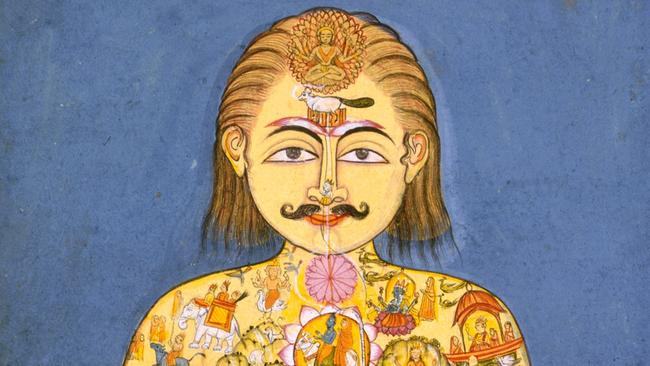

But it was Tantra too, with its emphasis on the corporeal, that conceived of the idea of the Yogic Body whose image is so often illustrated in Yoga studios. Leaving out the fine details, the body is broadly thought of as structured around seven Chakras or wheels aligned up the spine from the pelvic floor to the skull.

The feminine power of Kundalini lies coiled like a serpent – “kundalini” means coiled – in the lowest Chakra, and the adept seeks to awaken that power and raise it through the Chakras until at the very top it unites with the male principle under the skull, leading to an inner and spiritual version of the sexual communion of Tantric sculpture, the union of the male and female principles in the wholeness of enlightenment.