The Shards book review: Bret Easton Ellis no longer cuts it

The Shards is a two-dimensional book written for an almost extinct phylum of reader: those with protracted attention spans and time.

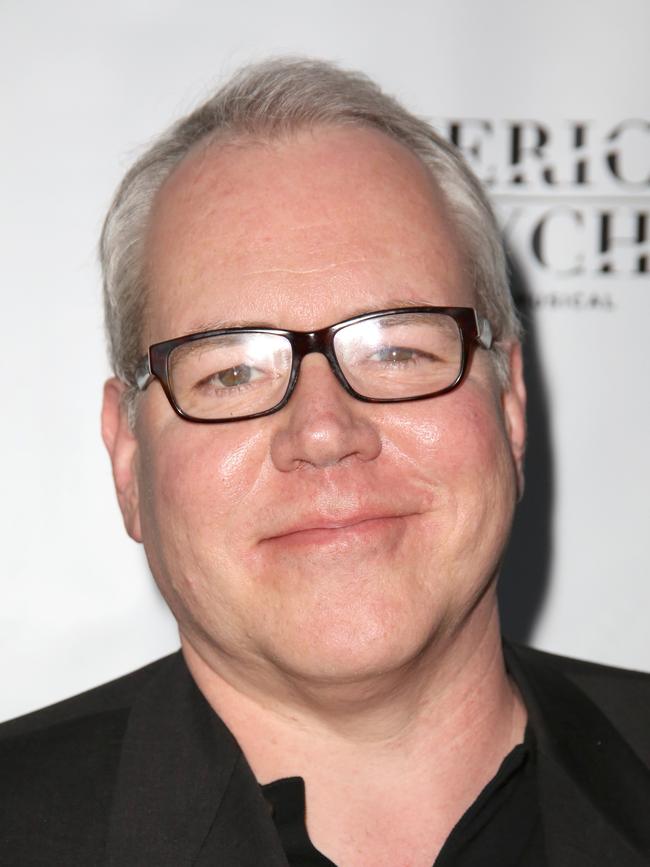

It can’t be easy being Bret Easton Ellis, now 59, pink, portly, and predominantly recognised, like Martin Amis, for transgressive postmodern novels published three or more decades ago – in Ellis’s case, his debut Less Than Zero (1985), which was followed by American Psycho (1991), the book that bottled the zeitgeist. The film adaptations (1987 and 2000 respectively) only served to amplify his notoriety. Since then, Easton Ellis has written four forgettable and formulaic novels, a short story anthology, a polemic about privilege, and The Shards, his first novel in 13 years.

The Bennington-educated son of a successful, alcoholic, “semi-abusive” LA property developer, Easton Ellis is, perhaps, the most patrician of his literary peers, with the added cachet of being 1.8m (six feet) tall, gay, and, as he once noted in relation to his old rivalry with Jay McInerney, having “a bigger dick”.

Street cred was bestowed by a propensity to addiction – Less Than Zero was drafted during a crystal meth binge, and, more recently, there was a heroin phase, and there were benzodiazepines and alcohol. Easton Ellis conceded to having been “really incredibly f--ked up all the time. I drank and did every drug conceivable, and I was really paranoid and freaked”.

These factors – the narcotics, the benzos, the paranoia, the sex, and the elitism – serve as the foundation of The Shards, a metafictional literary thriller of sorts featuring Easton Ellis as the midlife narrator recalling himself as a bisexual 17-year-old at the wealthy Buckley School, his alma mater, in 1981, just as a sadistic serial killer begins making the news.

The ludicrous volume of the book alone – 608 pages – is a statement not only of its importance, but of that of the author, who, like a literary Louis Quatorze, expects to hold court. Weighted by pointless detail, the paragraph-long sentences amount to so much waffling, and the plot frequently drags.

The controversial tracts, too, feel jaded. For example, the licking of anuses – always a big thing with Easton Ellis – is now old hat even with private-school students, who can access it on their smartphones, but the pulse points of his narratives are always the same.

Sex scenes in Easton Ellis novels are never contextualised by happiness. In this fictional universe, desire must be punished – not by conscious judgment (he’s too urbane for that), but by the symbolic language of trauma or unconsciousness. He loves drugs and murder for this very reason, and never permits his narrow characters contentment. Brittle or hostile satisfaction is as far as it goes and even then, it’s often parenthesised by suppressed suffering.

The Shards in particular betrays him as a closet puritan. The degree of punishment for sexual desirability is calculated in its extremity – among other “amendments” by the serial killer, one character has her breasts gouged out and replaced with cats’ heads. Easton Ellis also labours over revulsion, making a point of fusing it with sex, an alignment that, as it is with many LGBTQIA people in patriarchal cultures, may well have been formative.

Easton Ellis writes: “The expression on his face when he realised I wanted to have sex was the worst moment I ever shared with Matt Kellner. He looked at the hard-on jutting up and making a tent in my tennis shorts and then back at my face as if he were appalled. I’d never seen this expression before. It was almost a parody of fear and over-exaggerated disgust … ‘What the f..k are you doing?’ Matt asked, backing away. ‘What do you want to be? Boyfriends? You think we’re gonna be boyfriends? Are you f..king crazy? Get away from me.’”

One of the most interesting aspects of the novel is the narrator’s growing acceptance of his own homosexuality. His girlfriend “Debbie”, a lascivious heavy drug user whom he sexually endures (“What did it matter, what did anything matter, nothing mattered, I realised, panting”), and “Susan”, a sophisticated, “low-key” friend, appear to be fragments of reclusive Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Donna Tartt, whom Easton Ellis recently revealed he dated at Bennington and who dedicated her internationally best-selling debut, The Secret History, to him for a “generosity” that “will never cease to warm my heart”.

Again, like multiple characters in Easton Ellis novels, “Debbie” is mostly depicted through a pornographic prism (“pink panties”, “plush lips”, “voracious”, “slick and wet”, “stiffening nipples”, “vulva open and hot”, etc.), and his desirable male characters fare no differently.

Of his fictional adolescent male lover, Easton Ellis writes, “I didn’t want anything from him except his full-lipped mouth surrounded by light razor stubble, his muscular thighs, the chest with defined pectorals that tapered into a tier of abs, the small line that crept up from the patch of brown pubic hair and ended at the knot of his navel … and his ass, pale and tight and dimpled, very lightly dusted with blond down.” Tellingly, he adds, “At first it hardly mattered to me what resided within this form.”

A disciplined, masterful, and original stylist, Easton Ellis lacks, and has always lacked, heart. This practised detachment, a class marker, once worked because style in Less Than Zero and American Psycho was in itself the substance – compensatory, satirical – but in the era of Covid, war in Ukraine, and the cost of living crisis, it appears antiquated and irrelevant.

Easton Ellis is a beautiful technician, but his spirit is spent. There is no longer any majesty in his narratives, and nor is there any love. The Shards, for all its structural excellence, is a two-dimensional book about two-dimensional people hurting other two-dimensional people, and written for an almost extinct phylum of reader: those with protracted attention spans and time.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke’s new book, Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine, is now available online

The Shards

By Bret Easton Ellis

Allen & Unwin, Fiction

608pp, $45

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout