The road more travelled

THE National Museum of Australia's Travelling the Silk Road exhibition has the pervasive feel of being addressed to a clever schoolchild.

HUMANITY has produced three great civilisation clusters: the Mediterranean-European; the Indian, and the Chinese-Japanese.

Over the centuries, these centres have moved their centres of gravity, spread beyond their original boundaries, absorbed and civilised barbarian invaders, replaced or overlaid tribal cultures, and affected each other in ways that continue to be unpredictable.

Thus today, the rise of China is due to that nation's economic and technological modernisation, which means Westernisation, and yet that process does not extend to some of the human and social values which we consider the most valuable parts of the Western heritage.

Ethnic, linguistic and religious links between these clusters have existed for centuries, in spite of the vast distances that separated them. Greeks, Romans, Celts, Germans and Slavs are all related ethnically and linguistically to the peoples of Persia and India, in virtue of their common Indo-European ancestry. The reconstruction of the family tree of this language group was one of the great achievements of 19th century linguistics.

Eurindian connections have a long history, but the conquests of Alexander the Great increased exchanges in both directions and eventually led to one of the most significant instances of transcultural artistic exchange, the adoption of the figure of Apollo as prototype for the human representation of Buddha. After the time of Alexander, the Byzantine empire and later the Muslim world continued to act as conduits between East and West.

China was much further away, and there was little if any direct contact between it and the Mediterranean world in antiquity. China was even a long way from India, separated by massive mountain ranges, and both ethnically and linguistically completely foreign.

Yet there were important connections, although they were curiously one-way. Perhaps it was because India was such a fertile breeding ground for religions, while neither of China's two home-grown and complementary systems of belief was exactly a religion: Confucianism was an ethical doctrine and Taoism originally a primitive animism which had been refined into a form of mysticism. Buddhism, which had evolved into a religion, seems to have filled an important gap.

Buddhism originally spread to China not through the activities of proselytising missionaries, but through a kind of contagion, transmitted by merchants travelling between these regions, carried incidentally along with the goods they risked so much to sell in distant but lucrative markets.

The main route that led across the Eurasian continental mass was named the Silk Road - since this was one of the most precious of the merchandise traded along it - by a 19th century German traveller and scholar, Ferdinand von Richthofen, and was subsequently explored and studied by such scholars as Sven Hedin and Aurel Stein, the first European to be shown the extraordinary library of sacred texts stored at the Dunhuang monastery, at the Chinese end of the road.

The Silk Road was never a paved carriageway like the Roman road system, but more like a human equivalent of the pathways that ants find through or around obstacles, and which, once marked, are followed invariably by columns of their fellows. This fascinating human trail is the subject of an engaging, if sometimes slightly irritating exhibition that comes to Canberra's National Museum of Australia from the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

I have commented before on the very different philosophy and aesthetics of display in art galleries and museums. There is some justification for such a difference, but museum shows can be annoying when they are full of populist effects, brash didactic material that overshadows the artefacts they are meant to explain, and worst of all, noisy sound effects and insistent voiceover loops. Behind all this seems to lie the assumption that the target audience consists of school children, or of adults with the attention span and comprehension of 12-year-olds.

The Silk Road show does have the pervasive feel of being addressed to a clever schoolchild. The information panels are deliberately very brief, with the inevitable risk of superficiality, and some of the language is colloquial. On the other hand, much of the didactic material is very well done, like the analysis of a Tang dynasty painted scroll showing the stages of the manufacture of silk, supported by a video of the process. We learn, for example, that each cocoon is composed of a single thread of silk, so that once the end is found, the whole thing can simply be unwound.

The exhibition has a very simple structure, based on the four greatest centres along the main line of the east-west route: Xi'An in China, Tarfur, Samarkand and Baghdad. We begin in Xi'An in the Tang Dynasty, apparently at the time the biggest city in the world and a surprisingly cosmopolitan place that even had a community of Christians, as evidenced by a rubbing of the Nestorian Stele, an 8th century stone slab inscribed with Chinese characters and Christian symbols. There is a short review of the various religions that flourished or migrated along the Silk Road, but it is extremely cursory, and barely addresses the reasons why one belief or another may have met with success or succumbed to a rival system.

The question is obviously of interest, especially when we ponder the hardships, danger and loneliness of these vast empty spaces, alternating between extremes of heat and cold, of boredom and the sublime. In these harsh conditions, one easily imagines strangers sitting around a fire arguing whether there is a single providence that shapes their ends, or whether the cosmos is the theatre of an eternal struggle between good and evil, or whether indeed all suffering is merely an illusion produced by desire and fear.

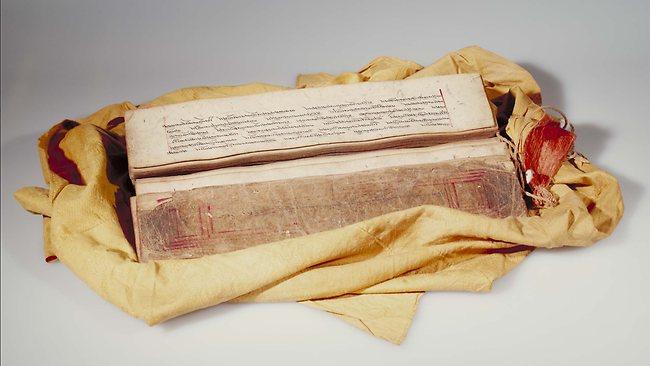

This section is also an opportunity to recall that paper was a Chinese invention, to illustrate the process, and to review other materials that have been used since the invention of writing 5000 years ago. These include clay and wax tablets, papyrus and then parchment, made of sheep or goat skins, which began to spread in the Christian era. The Chinese invention of paper was adopted first in the Islamic world and then Europe, where large-scale manufacture was established by the middle of the 15th century.

This is a first point at which the exhibition is rather misleading, if not actually disingenuous. We are told that the adoption of paper in the Islamic world led to an extraordinary blossoming of scientific knowledge in Baghdad, and that is plausible enough as far as it goes; but it was in 15th century Europe that the availability of paper had a truly dramatic effect, making possible the invention of printing, which can properly be said to have revolutionised human knowledge, and which was significantly prohibited in the Muslim world.

From Xi'an we move on to Turfan, where there is a reconstruction of a market with its various products, an interactive display where we can smell some of the precious perfume oils that were traded, all with a taped soundscape that is, fortunately, not too intrusive. Most interesting of all is a reconstruction of the underground irrigation channel, or karez, that carried water from a nearby river and groundwater from the mountains, without the evaporation loss that affects most forms of irrigation, and turned what would otherwise be arid desert into lush gardens filled with melons and grapes and other produce.

The third centre is Samarkand which, before the Muslim conquest, was the capital of the Iranian Sogdians, and the exhibition includes reproductions of two beautiful frescoes of their warrior hero Rustam, riding with his knights and fighting a fearsome dragon. Here and elsewhere through the exhibition there are tantalising glimpses of a theme that, treated in more depth, would make an outstanding exhibition: the transmission and exchange of formal decorative motifs between great centres such as Persia and China: we see, for example, how Chinese weavers borrowed certain designs from Persia but then transformed the patterns with a different decorative content.

We come finally to Baghdad - or almost finally, because the show has a coda on sea-trade - and we find ourselves in the glorious age of Harun-al-Rashid and the ensuing centuries, a time when the intellectual and artistic refinement of Baghdad made a striking contrast with the pitiful state of Europe in the centuries after the fall of Rome. In the West, originally barbarian peoples such as the Franks and Anglo-Saxons were trying to rebuild civilisation from the ruins while under siege from new and more savage barbarians. In the East, a picture is painted of a cultural environment effervescent with the spirit of intellectual enquiry, and making spectacular progress in all sorts of directions. Various texts with scientific diagrams, as well as models of a water clock and an astrolabe, are displayed in support of these claims.

There is no denying the significance of Muslim learning in these fields, or their real achievement. It is admirable such scholars as the Persians Avicenna or Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi adopted, preserved and developed knowledge in their respective disciplines. But this area is often misunderstood and sometimes wilfully misrepresented. Here, one label informs us that between 1100 and 1200, "scholars translated scientific works from Arabic into Latin, setting the stage for the European Renaissance". This is a disturbing example of anachronism to come from a learned institution. What was evolving in the period cited was not the Renaissance but the High Middle Ages, the age of scholasticism. The movement we know as the Renaissance would not begin for another three centuries.

Scholarship in the Islamic world is a fascinating subject, but we need to be specific about the times, the places and the peoples involved, as well as about their sources and the extent of their original contribution. Most of what they knew, in philosophy, cosmology, astronomy, mathematics, anatomy, botany, etc - as is equally true of our own medieval forebears - was learnt from the Greeks. In certain particular areas, particularly mathematics, astronomy and optics, Islamic scholars went beyond their sources. They may have improved the astrolabe, as is claimed, but the 2006 reconstruction of the much more advanced Hellenistic device known as the Antikythera mechanism throws this into doubt.

The irony about the quite common overestimation of our debt to Islamic civilisation is that it declined from its golden age in the 13th century and subsequently remained largely ossified, while Europe went on to create the modern world. And even when some precious and otherwise lost texts were indeed preserved in an Arabic translation, one can't help wryly reflecting that they would probably not have been lost in the first place had not the Arabs overrun the Byzantine empire. One's gratitude is of necessity qualified in such circumstances.

Travelling the Silk Road

National Museum of Australia, Canberra, to July 29