The ones that got away: the best art shows killed by Covid

Of all the exhibitions that I was unable to see, two stand out as causes of genuine regret: the NGV’s French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and TMAG’s show on T.G. Wainewright

In the turmoil of lockdowns and border closures that overtook Australia in the second half of this year, and among many other more serious consequences, exhibitions around the country were constantly deferred, cancelled, or simply closed. Many spent a good part, and sometimes almost the whole of their projected run, shut down and without visitors. Even when galleries were open, border closures frequently made it impossible for anyone to visit from interstate.

Of all the exhibitions that I was unable to see, two stand out as causes of genuine regret. The first of these was French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which I had intended to visit at least twice; travel plans and flight bookings were changed two or three times before it became clear that it would be impossible to see it at all.

This was not, of course, the first significant exhibition of French Impressionist painting in Australia; as probably the most popular of all styles of painting with the museum-going public, the movement has been and no doubt will continue to be the focus of many shows. This one, however, was distinguished by its scale and depth, and by the range of artists before and after the Impressionists considered more narrowly.

To judge by the catalogue, there was a good coverage of the Barbizon School, including artists with classical roots like Corot and others more romantic in inspiration, like Theodore Rousseau. It was just a little disappointing that Corot, who is so important in this story, was rather thinly represented; it would have been desirable to include some of his earlier work in order to support one of the exhibition’s implicit arguments, which was to draw attention to the central role of Pissarro as Corot’s pupil and in turn as an older companion and mentor of Cezanne and others.

Eugene Boudin, who directly influenced Monet in the adoption of plein-air painting, is particularly well-represented, and there are several paintings by Jongkind, Daubigny and others, all of whom however end up being rather monochrome, and because they liked to paint northern marine views, cold and grey. The trouble with these artists is that they have lost touch with the classical tradition of landscape, with its compositional and structural conventions, but have not yet developed the optical resources of the impressionists, for whom the same scenes would be suffused with light and complementary colours.

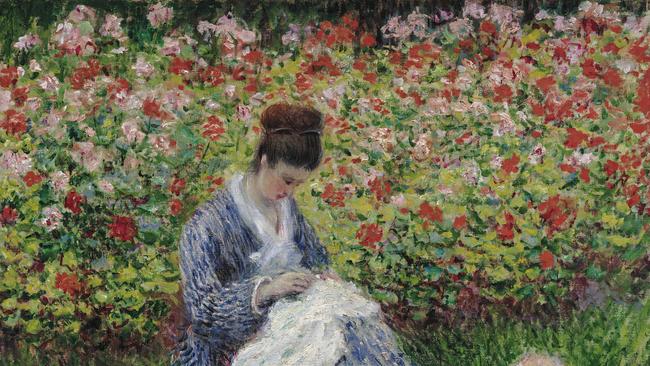

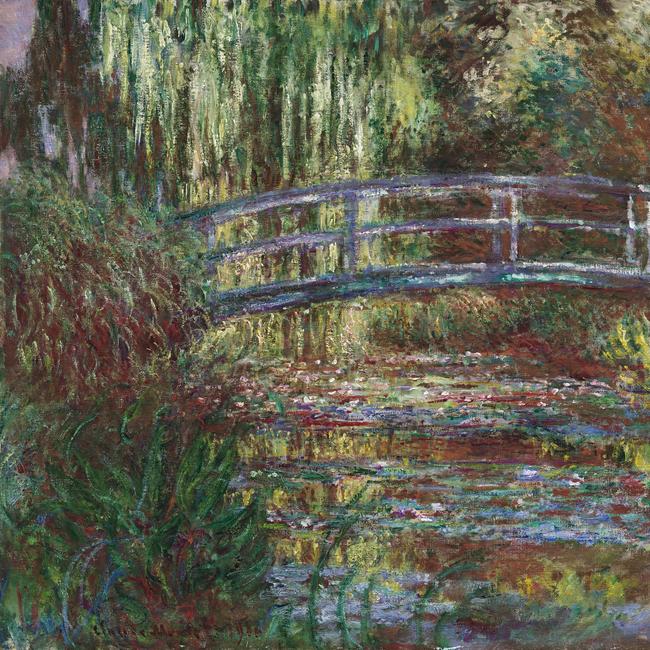

There was a good selection of paintings by Monet from the Museum’s extensive holdings, all gifted by wealthy collectors who purchased them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as Renoir and others. Pissarro’s special role has already been mentioned; there were several pictures by Cezanne, including an awkward group of bathers from his early, ugly-duckling period and much stronger ones from a couple of decades later. A powerful still life is set beside a rather weak one by Berthe Morisot in the catalogue; Morisot’s work is pleasant enough on its own, but here becomes the foil to Cezanne’s incomparably more powerful sense of form.

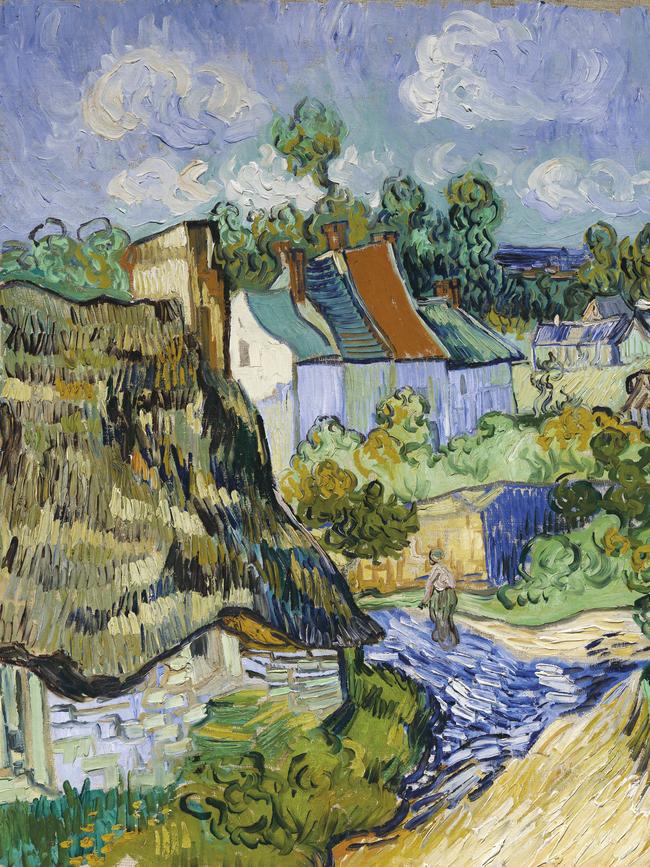

Degas, one of the most impressive and intriguing painters of this period, is represented by several memorable pictures, including the double portrait of his sister and her Neapolitan husband Edmondo Morbilli, which is at once a homage to Ingres and yet incomparably spontaneous and personal. Finally there is a selection of neo-impressionist images – again a connection to Pissarro who adopted the divisionist style for a time – and a few examples of post-impression.

The other exhibition that I regretted missing was an important contribution to the story of Australian colonial art, and particularly to the history of art in Tasmania. Thomas Griffiths Wainewright’s name may not be familiar to many museum visitors today, although anyone acquainted with colonial art in Tasmania will have seen some of his fine portraits from the early 1840s.

Readers of Oscar Wilde’s essays may also recall one with the intriguing title, “Pen, pencil and poison” (1889). In the second half of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th, Wainewright was in fact notorious for several murders that were attributed to him and his wife Eliza, even though none of these charges was ever proved or even ended up in court. The lurid stories that grew up around his name overwhelmed his modest reputation as an artist, not helped by the fact that most of his production appears to have been lost.

Even today the truth is not easy to establish; the exhibition and its beautifully-produced catalogue certainly help us understand the circumstances of Wainewright’s life in much greater detail than before, but this only serves to deepen the mysteries about his actions and motivations at various points in what can only be described as a career of self-inflicted tragedy.

Wainewright (1794-1847) was born into a well-to-do and cultivated family. He received a good education at the Greenwich Academy, run by the famous Charles Burney, himself a distinguished classical scholar, so he must have acquired a sound knowledge of Greek and Latin, even if later evidence suggests that his culture was more dilettantish than scholarly.

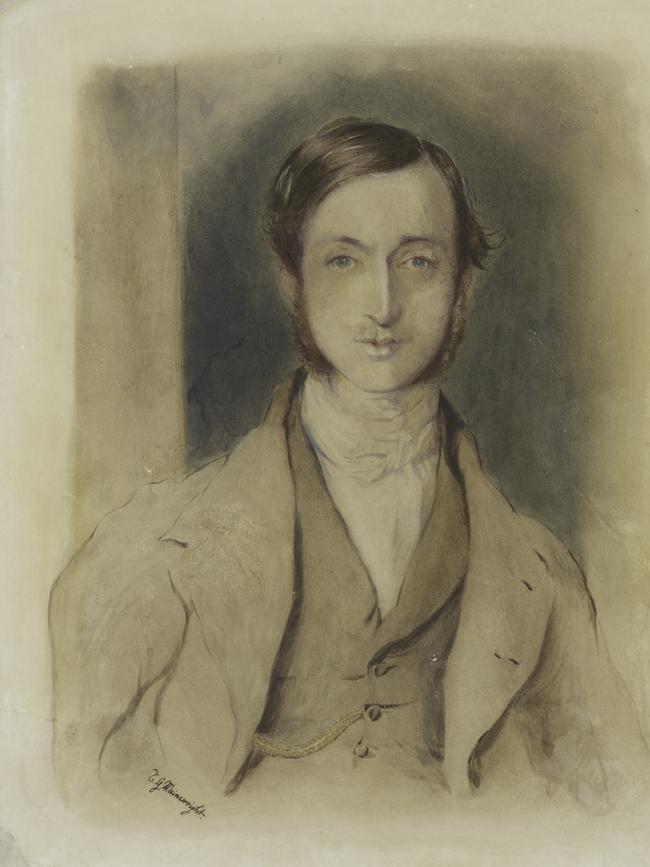

He was apprenticed successively to two portrait painters but left each after an unusually short time in circumstances that are typically obscure. He spent a disastrous year or so in the army in 1814-15, ending in a kind of nervous breakdown. In spite of all this, surviving works like his portrait of Henry Foss (c. 1813-20) show that he had considerable talent and a certain natural elegance; between 1821 and 1825, six of his paintings were accepted for exhibition at the Royal Academy. At the same time, he became friendly with Charles Lamb and other authors and started writing art criticism under one pseudonym and a more general autobiographical pieces under another for The London Magazine and other publications.

It is surprising that the exhibition catalogue did not reproduce at least a selection of these pieces, which were published in a collected edition by W. Carew Hazlitt in 1880 and are thus relatively easily accessible (this was the source that Wilde consulted). The autobiographical articles are expressions of the culture of dandyism that first arose in the Regency years, and whose most famous exponent was Beau Brummell (1778-1840), although the idea of the dandy continued to inspire later authors as different as Baudelaire, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam and Joris-Karl Huysmans and evolved in their hands into an existential attitude in the face of the horror and impersonality of mass society.

Wainewright’s articles luxuriate in the evocation of elaborate aesthetic interiors which are the forerunners of those Huysmans writes of in his notorious novel A Rebours (1884), the unnamed French novel that plays an important role in Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890-91). He imagines himself in a splendid room full of paintings, mirrors, precious rugs, antique books, and so forth: the texts are so plangently self-indulgent and narcissistic in tone that one could be tempted to think them completely fictional, except that we know that Wainewright did indeed live at this time in an opulent house and – from subsequent auction records – that he did own many fine antique books.

His way of life, however, was delusionally out of proportion with his financial means, even though he enjoyed a regular income from funds left in trust for his benefit in his grandfather’s will. The fact that he was left an income but deprived of access to the capital, indeed, suggests that his grandfather had already recognised Wainewright’s irresponsible, if not actually unhinged, character. This extravagance is what was said to have motivated the murders of which he is accused, although it was possibly his wife who poisoned three people, including her own mother. Financial need certainly motivated the crime for which he was eventually apprehended and convicted: he forged the signatures of three trustees to get access to the capital from his grandfather’s estate. This was a very considerable amount of money, but that too was soon squandered.

Extraordinarily, the forgeries were carried out in 1822 and 1823 but not discovered until 1835. Wainewright was arrested, convicted and sent to Van Diemen’s Land, arriving there in 1837. He himself described how the passage out, and life as a convict, were a nightmare for a man of his almost neurasthenically refined sensibility, surrounded by ugliness and filth, and by the dregs of humanity whose inarticulate speech was mostly composed of obscenities and blasphemy.

The book reproduces two pictures that are believed to be self-portraits: one, of a smart and fashionably-dressed young man, is dated rather unsatisfactorily between 1813 and 1830; the other is a drawing in Tasmania, Head of a convict, very characteristic of low cunning and revenge (c. 1843), whose title alludes to the style of physiognomic diagrams of character types. The artist must be about 49 years old, and yet looks oddly young and even effeminate, in spite of his moustache, with large staring eyes.

After some hard years at the beginning, Wainewright seems to have obtained more freedom, no doubt because his talents were recognised and were far better used making portraits of the important figures in the colony than working at the hard labour for which he was constitutionally unsuited.

What is so remarkable about these portraits in general is the grace and lightness with which he endows his sitters, even when his own existence was weighed down by disgrace, poverty, physical discomfort and increasing illness. And in spite of the reference to revenge on his self-portrait, he seems able to look at these men and women who enjoy everything that he once had without a trace of resentment or bitterness.

This is probably not as paradoxical as it sounds. One can only assume that the joy of exercising his craft, of deftly capturing a likeness while making a beautiful picture, brought him real happiness and relief, and the feeling of communing with beauty and refinement instead of wallowing in grossness and degeneracy. Making these understated pictures, executed with the minimum of drawing and the most restrained colour, was once again to be an aesthete and connoisseur instead of a despised convict.

It is in a similar perspective that we should look at the two remarkable watercolours that he made in Hobart, both strongly influenced by the style of Henry Fuseli, whom he had known well in London. Both are primarily female nudes, evidently painted from memory; one is of an obscure medieval subject, but the other is from the late antique story of Cupid and Psyche. The vase in the foreground reminds us of Psyche’s last trial, and of the Stygian fumes that had put her into a deathly sleep. Here Cupid awakens her with a kiss, just as perhaps Wainewright dreamt of waking to find that the horror of his convict life was nothing but a terrible nightmare.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout