The naked truth about men and art’s feminisation of the form

Paintings of the male nude in the late 18th century raise interesting questions around the intersection of erotic and aesthetic taste.

Eros in art

Neoclassicism

Among the less admirable aspects of the golden age of French literature was the rise of a group of jingoistic critics who asserted that modern French authors had not only equalled but surpassed those of antiquity.

This became the topic of a debate known as the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns which spread to other countries as well, although it remained most contentious in France where, ironically, all the greatest contemporary authors were supporters of the Ancients and most of the writing held up as exemplary by the Moderns has never been read since.

The final stage of this controversy, which coincided with the last years of Louis XIV’s reign, was known as the Quarrel of Homer. In 1714 Antoine Houdart de La Motte, who could not read Greek, published a bowdlerised edition of the Iliad, meant to be suitable for the more refined tastes of his time. Madame Dacier, a prominent Greek scholar who had published a prose translation of the Iliad in 1699 replied in defence of Homer. But even more importantly, in England Alexander Pope began his great verse translation, which came out from 1715 to 1720 and was so successful that it allowed him to purchase his villa at Twickenham.

The Quarrel of Homer had an effect that Houdart could never have anticipated: it provoked a massive renewal of interest in Homer and in Greek literature in general and soon combined with other developments to form a tidal wave of neo-Hellenism. Greek tragedy was at last translated and read. Winckelmann published his Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke (Reflections on the imitation of Greek works) in 1775 and his Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (History of the art of antiquity) in 1764; the second of these books is often considered as the founding text of both modern art history and archaeology.

Ottoman power began to wane in the second half of the 18th century and it was at last possible to visit Athens. James Stuart and Nicholas Revett visited Greece in 1751-54 and made accurate drawings and measurements of the great monuments of Athens and other cities. They returned to London in 1755 and published their Antiquities of Athens in 1762. The Elgin Marbles were acquired and exhibited at the British Museum by 1816, revolutionising the modern understanding of ancient art.

The prestige of Paris also declined in the decades after the Sun King’s death in 1715, and the centre of the new interest in antiquity was once again Rome (and to a lesser extent Naples, where the excavation of Pompeii began in the second half of the century).

Winckelmann lived mostly in Rome from 1755 until his death in 1768, and it was here that other artists like the German Anton Rafael Mengs (who moved to Rome in 1741) and the Scotsman Gavin Hamilton (in Rome by 1744) were developing the new style that became known as Neoclassicism.

Hamilton’s Achilles lamenting the death of Patroclus (c. 1760-63) reflects the new interest in Homer as well as the rejection of Rococo triviality in favour of grandeur and pathos, while his Oath of Brutus (c. 1763-64) illustrates the other great source of inspiration for Neoclassical artists, which was the history of Rome, and particularly stories of moral courage and virtue from its republican period, which resonated with the political thought of the Enlightenment, including new conceptions of both the citizen and the state.

The subject of this painting, indeed, is the founding of the Roman republic by Brutus, the ancestor of the Brutus who helped assassinate Caesar. On the left we see the expiring figure of Lucretia, the noble young woman who has killed herself after being raped by the king’s son; in the centre Brutus holds up the dagger with which she has stabbed herself and vows to overthrow the monarchy.

It is not hard to see the influence of this composition on Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784). Ever since the 1660s, the most outstanding students at the Academy in Paris had vied for postgraduate scholarships to live and work at the French School in Rome. Thus the leading French artists had always been steeped in the classical tradition taught in Rome, but this was especially true at this time, when the Academy in Paris was comparatively lacklustre and the artistic life of Rome was again vibrant.

David famously failed three times to win the annual Prix de Rome before finally succeeding in 1774; he was in Rome from 1774 to 1780, but went back in 1784 expressly to paint this picture, whose mood seems so evocative of the French Revolution that we can forget that it was a royal commission, five years before the events in which the artist would be politically involved and complicit.

The story of the Oath of the Horatii is also from the early history of Rome, well known from Livy’s Roman histories and in France particularly as the subject of Pierre Corneille’s famous tragedy Horace (1640).

To avoid a catastrophic loss of life, the cities of Rome and Alba Longa agree that their war will be settled by combat between three warriors on each side. Rome is represented by the three Horatii brothers, Alba Longa by the three Curiatii; two of the Romans are killed and all combatants are wounded, but the last of the Romans, Publius Horatius, contrives to separate and kill his three opponents.

The story has a distasteful sequel, when Publius comes home in triumph, but his sister, who was engaged to be married to one of the Curiatii, breaks down in grief at his death; indignant at this lack of patriotism, Publius kills his sister. David’s painting, as many have observed before, is clearly divided between the two sexes: on one side, the three brothers taking an oath to fight for their country, while their father holds up their swords; on the other, the anxious and grieving figures of the sisters. Strong, virile bodies with wiry muscles standing in attitudes of tense alertness contrast with swooning, nerveless feminine bodies collapsing onto the backs of chairs.

From this painting we might assume that Neoclassical art tended to emphasise the physical and psychological differences of the sexes; it is easy to imagine a connection with new political and philosophical ideas about life in harmony with nature and about the role of citizens of each sex in an ideal state, in contrast to the promiscuity and lack of differentiation that had prevailed in the lives of the upper classes in the mid-18th century, when men were clean-shaven and both sexes wore powder and wigs.

The truth, however, is much more complicated. When David painted The Intervention of the Sabine Women in 1798, after the appalling butchery of the Terror in which he had been personally involved, it was again to Roman history that he went for a story of reconciliation. Here, also from Livy and from the earliest days of the city, is the sequel to the Rape of the Sabines. The Romans, lacking wives, had carried off Sabine girls to be their brides; but now, as the two sides are about to fight, the women intervene, showing the children they have borne to their new husbands and demonstrating that the two peoples are now one.

One notable thing about this picture is that it is the women who occupy the centre of the composition and who take the initiative. The other is a certain curious softness and effeminacy in the bodies of the men. The same qualities are perhaps even more apparent in the male nudes of David’s later Leonidas at Thermopylae (1814).

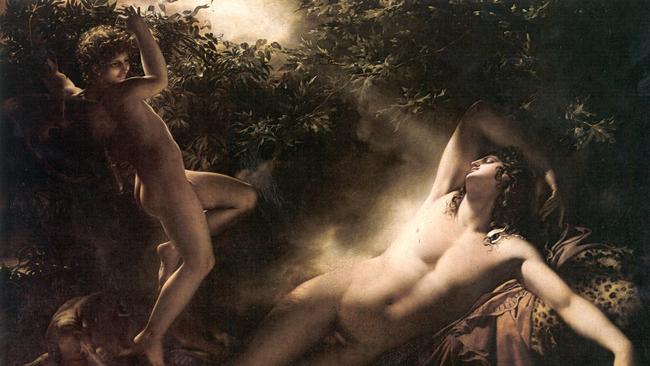

This phenomenon is even more striking in other painters. Consider Anne-Louis Girodet’s The Sleep of Endymion (1791) in which the body of the naked youth is caressed by the light of the moon, his lover. It is extraordinary to think that a picture that seems so blatantly homoerotic could have been painted in the middle of the Revolution. Gérard’s Cupid and Psyche (1798), like much painting of the Empire period, is perhaps unintentionally camp. Bodies as smooth as sugared almonds would remain a staple of later academic painting.

Probably the most talented, influential and in his own way original of David’s pupils was Jean-Louis-Dominique Ingres (the name is pronounced roughly like “angry” without the “y”). In 1801 he won the Prix de Rome for his painting The Ambassadors of Agamemnon at the tent of Achilles, another Homeric subject.

At the beginning of the Iliad, Achilles quarrels with Agamemnon and withdraws from the fighting; this allows the Trojans to gain the upper hand, so that by Book IX Agamemnon, in desperation, sends ambassadors to Achilles’s tent to apologise for insulting him and to beg him to return. Achilles refuses, and does not rejoin the fighting until after his friend Patroclus has been killed by Hector in Book XVI.

But what is most striking about the picture today is its peculiar collection of male nudes, especially the swaying figure of the young Patroclus, far more prominent than the shadowy Briseis in the entrance of the tent. There are many more pictures like this which appear profoundly ambiguous today: are they the reflection of homoerotic feeling or the unintended effect of certain ideas about the nude and of the period’s love for a precious level of finish? Or does the truth lie in some intersection of erotic and aesthetic taste?

However we answer these questions, we are once again left to wonder how such an ostensibly effete sensibility could coincide with the brutal years of the revolution and then the apogee of France’s political and military power under the seemingly invincible Napoleon. Ultimately, this appears to point to the growing dissociation between art and public life in the new mass society that is just beginning to emerge at this period.

A final case is still more extreme. In Aurora and Cephalus (1810) by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, the teacher of Géricault and Delacroix, the body of the young man loved by the goddess of dawn is unprecedentedly soft, nerveless and effeminate, resting in sleep on a bed of clouds. Another version, painted with a companion piece in 1811 for Prince Nikolay Yusupov, is nearly identical except that the head of Cupid has been moved to mask the youth’s private parts.

But Guérin outdid himself in the pendant Morpheus and Iris, in which the androgynous and lazily stretching boy is uncovered and exposed to the viewer. Few female nudes are as passively offered to us in this way; but the presence of Iris as spectator or even voyeur within the composition suggests yet another level of interpretation – that it is not merely homoeroticism, but something that we have not seen before, an evocation of male submission and female domination.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout