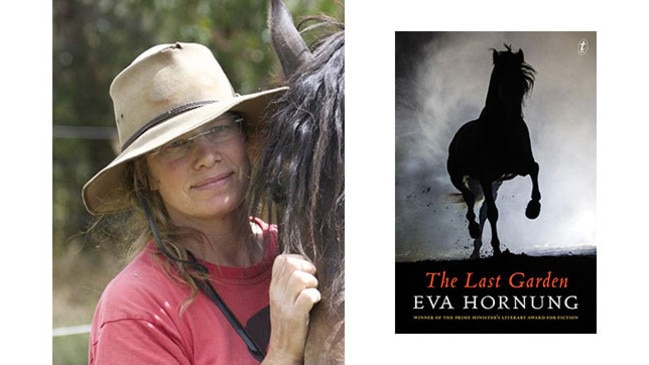

The Last Garden: Eva Hornung on rigid doctrine’s false redemption

Eva Hornung has taken the bare bones of German immigrants’ history and built a tale of faith and renewal.

In the early 19th century, 38 German Lutheran families, escaping the threat of persecution under the Prussian king, arrived in Port Adelaide, eventually establishing a small settlement in the Adelaide Hills. It was the first of several waves of German immigration to the area, the newcomers building villages and cultivating the land, all the while holding to their own religion, customs and traditions.

In The Last Garden, Eva Hornung takes the bare bones of this history and transforms them into an allegorical tale of faith and renewal. Her first novel since the extraordinary Dog Boy (which won a Prime Minister’s Literary Award in 2010), this is a quiet and subtle piece of writing, exploring not only the stultifying effects of social and spiritual isolation but also the prodigious healing power of the natural world.

Fifteen-year-old Benedict Orion returns home from boarding school one summer to find both his parents dead. Benedict’s father, “compelled to destroy anything that he considered to be part of himself”, has shot his wife and taken his own life. Only the time it took Benedict to walk from the station to the family’s farmhouse saved him from the same fate.

Walking along the dusty roads towards home, Benedict had determined it was time for him to finish school. He was “filled to the brim with promise”: he would prove his place on the farm, work beside his father, take up blacksmithing as a trade. But with the discovery of his father’s brutal act, Benedict’s future becomes something terrifying and unknowable.

Read Stephen Romei’s interview with author Eva Hornung

The day his parents are buried, Benedict runs from the farmhouse and takes refuge in the barn: “The barn alone gave him peace, for it was clean of memory. The barn was filled with the breathing of horses.” The horses become his link to the world, to life. They dull the “intolerable” pain of what he has experienced, affording each day “a faint rhythm, a tempo that could draw him into each night and then the day beyond”. And they give him a reason not to return to the house, to the ghosts of the past (his parents, his younger selves) that live there still.

Benedict’s only visitor is Pastor Helfgott, who brings food and other offerings from the community. Helfgott watches as Benedict grows increasingly distant, living “like a wild beast” and communicating only with the horses around him. He begins to wonder whether Benedict isn’t perhaps the Messiah for whom the community has been waiting:

Pastor Helfgott saw the boy … as if for the first time: a gold-haired and arresting young man with burning blue eyes. Angelic, somehow … He now truly felt a sense of destiny or design to the boy’s suffering.

It was Pastor Helfgott’s father who established the congregation, bringing them to this place of exile so they might live secluded from the rest of the world, freely practising their religion and preparing for the Messiah who would take them to “the last garden”. They are a congregation “welded together by suffering”, guided by the elder pastor’s teachings (gathered in The Book of Seasons, The Book of Building and The Book of Prayer).

But the elder Helfgott hadn’t anticipated that his own death would come before the “Aeon of Glory”. Without his stringent rule, the boundaries of the congregation have been progressively breached: members (including Benedict’s father) have travelled to the New World and brought back unorthodox notions; a growing prosperity occasions trade with “outsiders”; and the hardship on which the community was founded has given way to “wealth, comfort and desires”.

Alert to his inability to hold the community together, to be the same iron hand his father was, Helfgott persists with Benedict. He wants to keep him alive, bring him back to the congregation; to have the congregation again open their hearts to “their lost son”. But the more Helfgott and Benedict are in each other’s company, the less certain it is who is leading whom towards the light: “The boy had become more compelling and confronting to him than any single person had ever been. Lord, what are You teaching me?”

The Last Garden is a novel of juxtapositions. The Book of Seasons (the canon that decrees how each month will be spent) contrasts sharply with the life Benedict leads, his close connection with the natural world and his acute sensitivity to its moods and variations. The God-fox that haunts Benedict’s dreams echoes with the ever-looming figure of the elder Pastor Helfgott and the dogma he represents. And Benedict’s estrangement from the congregation is measured against Pastor Helfgott’s own insights into the purpose and good of their exile. There is a strange alignment between Benedict’s and Helfgott’s lives, and through that — each quietly taking from the other, each unknowingly giving — they are able to confront darker truths tormenting them.

In Benedict’s relationship with the horses — the way they enable him to endure — there are traces of Dog Boy (which tells of a young child kept alive by a pack of dogs). But where that novel concerned itself with the porous borders between animal and human, with raw physical survival, The Last Garden is more interested in the spiritual; in the way in which rigid doctrine, blind to the realities of a changing world, corrupts and stunts the soul.

This is a novel that is calm and patient in its telling, and almost hypnotic in its effect. What Hornung emphasises is that it’s neither our hopes for the future, nor the suffering of our pasts, that saves us. Rather, it’s in the act of living — the way we attune ourselves to the shifting demands of the world around us; the use we make of the time between “the first garden … and the last” — that redemption is to be found.

Diane Stubbings is a writer and critic.

The Last Garden

By Eva Hornung

Text Publishing, 237pp, $26.99