Eva Hornung’s Last Garden melds religion with tragedy in South Australia

Eva Hornung’s first novel in nine years ventures into a bestial world where tragedy and religion collide.

‘Hornung comes, does it not, to chasten us, to burn our souls and lay bare our sins … We squint in the white light of Hornung, dazed … Blaze when Hornung blazes upon you!”

If that sounds like a blazing blurb for Eva Hornung’s new novel, The Last Garden, well, it could be. It’s a mesmerising book by the talented, reclusive Australian author who used to write under her married name, Eva Sallis. But it’s in fact a description of the month by the religious exiles in the book, who follow an early Germanic calendar known as Hornung, the month of gathering. We know it as February.

“Yes, I did enjoy writing that bit!’’ Hornung says about the month with which she shares a name. She laughs, as she does often in our telephone interview. She’s at home, in the Adelaide Hills, where she runs a farm full of horses.

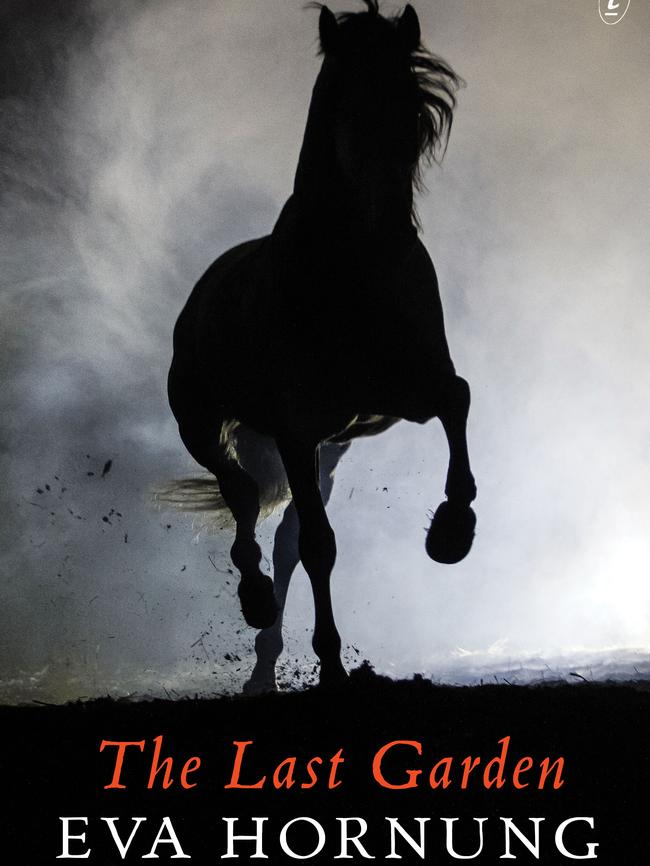

Horses are important in the new novel, as the cover suggests, but we will come to that later. This is Hornung’s first novel since the Moscow-set Dog Boy, about a six-year-old kid who is raised by feral dogs. It won the Prime Minister’s Literary Award in 2009.

Hornung, then Sallis, won The Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award for her debut novel, Hiam, in 1997. She followed that with regularly delivered works of fiction, and each was acclaimed by critics: The City of Sealions (2002), Mahjar (2003), Fire Fire (2005), praised as a “Cloudstreet of the Australian bush”, The Marsh Birds (2006) and Dog Boy.

With that track record, nine years is a long time between books. Hornung’s explanation is one with which every writer will sympathise: writer’s block. Her life was a bit difficult at the time. Her then eight-year-old son, Rafael, was suffering acute anxiety. She was no longer with her husband. It was concern for her son that made her break the writer’s block.

“I thought I would force myself to write a book for my son. I sat down literally to force myself to write, and I wrote the first paragraph of The Last Garden.”

Even that opening paragraph made her realise the book would not be suitable for an eight-year-old. Rafael, now 16, hasn’t read it yet but he has his mother’s approval to do so.

“I ended up following that first paragraph to wherever it led, and it led to all sorts of strange things,” Hornung says. “So it’s kind of hard to answer why I wrote the book or what I’m trying to achieve. But I did manage to express things that mattered to me.”

The novel opens, in the month of Nebelung, with a devastating event that would be right at home in good crime fiction:

On a mild Nebelung’s afternoon, Matthias Orion, having lived as an exclamation mark in the Wahrheit settlement and as the capital letter at home, killed himself.

Before turning the gun on himself he entered his “beautiful house” as if “blown by a harsh wind” and shot his wife Ada “through the heart as she stood by the sideboard”. “She crumpled into silence, a hush that he recognised as unique among hushes: the very end of everything.”

So after one page we have a tragic murder-suicide that demands explanation. One of the brilliant aspects of the novel is that every step taken towards a possible answer only raises more questions.

Unlike Dog Boy, which was ineligible for the Miles Franklin because of its non-Australian setting and characters, The Last Garden unfurls at home, probably in colonial South Australia, which took in a lot of Germans who had fled religious persecution.

“Yes, it’s set in Australia,” Hornung says. “But I was careful to keep it as a kind of parallel reality. It’s not history. It’s invented yet close enough to possible history. The place, the time, the historical context are all invented, but also all perfectly possible.”

Wahrheit, which means truth, is a millenarian settlement. It was set up in anticipation of Christ’s return but, as Hornung says, “the second coming is coming too late”. The small, closed community has fared well. It’s a happy sect, or happy enough. Again, Hornung does not know if there was a German second coming microcosm in colonial SA but says the existence of one would be “perfectly conceivable”.

“I just wanted the freedom to play around with this notion I had that religions and religious texts mediate between people and the natural world.”

The sect’s promised Last Garden, from which souls will be harvested on Christ’s return, is producing only decent crops. Wahrheit is a “place of virtue, harmony and peace”, until Matthias’s bloodshed changes everything.

The pastor, who still delivers the sermons written by his father, who founded the settlement, doesn’t know what to do.

… there were things Pastor Helfgott himself had never imagined, let alone spoken of in his sermons on hardship and struggle. Matthias’s act had no counterweight in goodness

… Wahrheit was not only shocked. Wahrheit was frightened …

These fears are heightened by the unexpected behaviour of the central character, Matthias and Ada’s 15-year-old son Benedict, who returns home from boarding school on the day of the shootings. Rather than seek comfort from other members of the sect — and one of the growing realisations of this book is how close a closed community can be — Benedict secludes himself on the farm.

He doesn’t enter the house but settles in the barn with the horses, led by an old mare named Melba. A young stallion named Fell agitates everyone. Hornung, who teaches riding at home and also uses her farm as a rehab centre for injured or ill horses, knows the equine mind well, and her writing about it is humorous.

Benedict doesn’t eat much, mainly oats. He doesn’t speak. Indeed the first time we hear him speak is more than halfway through the book, when he talks to a cat (another funny moment). He roams the farm “like a ghost”. But he works hard and grows lean and strong. He looks beautiful, almost Christ-like.

The pastor visits regularly. They eat together, with only the man of God speaking. He thinks, “The boy had become more compelling and confronting to him that a single person had ever been. Lord, what are You teaching me?” And later, “Lord, am I doing the right thing? Am I leading him to Your Light? Is he leading me somewhere else?”

The books that came to mind while reading The Last Garden include JM Coetzee’s Jesus novels and Nick Cave’s first novel, And The Ass Saw the Angel. When I mention this to Hornung, she laughs a lot. “Sounds like you’ve really floundered for a context for this book. It’s making me think the book’s a bit of a flop!”

She agrees the pastor does see Benedict as Christ-like, for a while. But to the author he’s just a boy. “He has had the past he knew and the future he expected stripped away from him. He is in crisis and grief. He rebuilds the self from the present. And the self he rebuilds is very innocent, very immediate and, from the outside, very beautiful.”

When Benedict does start talking he is calm, “almost expressionless”, but there are flashes of what could be anger. “F..k God and his wily ways,” he tells Helfgott. “F..k the Devil too, that little yes and no man.” Helfgott’s reply is curious: “Don’t speak lightly of the Devil, boy …”

Benedict seems to become less human, more animal. His commingling with the bestial world starts literally, in a beautiful passage where he helps a horse deliver a foal, his arm inside her up to his shoulder. Hornung sees this as two births: the foal’s and the new Benedict’s.

On seeing a kestrel soaring over grasslands and capturing a snake he “felt himself lift, felt a different arc to his breastbone, a fierce joy … He knew nothing: neither hopes nor memories. But he felt the pulse and quiver of their moods, their urgent concerns of the moment.”

Animals abound, from ants to horses. When a young woman visits Benedict and looks from him into the barn her “eyes retracted as a snail’s do when touched”. There are times, too, when he seems to think animals are humans. The fox is his father, a connection that further darkens the first mention of a fox, early in the book.

“I wanted to create a believable human figure who is so unmediated for in the natural world that he is for a time more permeable,” Hornung says. “So he’s more permeable to the drives and emotions of all the animals with whom he’s connected.”

Hornung is fluent in Arabic and most of her books have Middle East settings and explore the differences and tensions between Arab and Western cultures, particularly regarding women. The Last Garden, though, is perhaps her most personal novel. Her German father, Richard Hornung, was born in Palestine, in a religious German community called The Templers, who settled there in the 1860s to be near Christ’s birthplace. When Israel became a nation in 1948, the community was disbanded. Its members became prisoners-of-war of the British, were sent to Australia and spent time in detention camps in Victoria and SA.

Hornung was a viola player. He married a New Zealand artist and, after having eight children, they moved to Germany. Hornung was eight when the family returned to Australia. The children were home schooled, with music and art considered important. She didn’t see a TV until she was 16. Several of her siblings are professional musicians, including cellist Alfred Hornung, known for his Bach in the Dark performances.

She says her father’s experiences were “a point of departure” in the writing of the novel but she doesn’t feel it’s about him.

“My novels just pop out of the woodwork, so to speak. Quite often I would say it’s an idea more than a state or place that drives it. There’s usually some big idea pushing away and forcing me to write.”

And when it came to writing this book, the one that was a long time coming, she is grateful to another animal, at least metaphorically.

“Forcing myself to start The Last Garden was a good thing to do because once started books take you by the scruff of the neck like a dog. Once you start, you’re stuffed.”

Eva Hornung’s The Last Garden is published next week by Text Publishing.