The gilded lives of the Paget twins

This is a thoughtful and intimate account of the lives of Celia and Mamaine Paget, whose lives were linked by friendship and marriage to a bohemian world of mid-century writers and intellectuals.

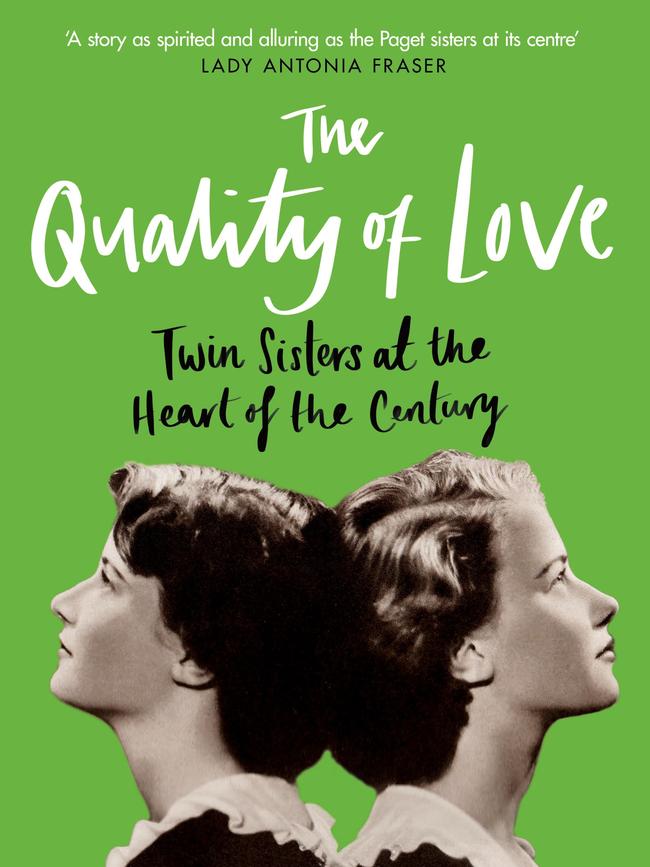

The Quality of Love: Twin Sisters at the Heart of the Century

Some reviews can be hard to write, despite the merits of a book under discussion. In the case of The Quality of Love, a thoughtful and intimate account of the lives of Celia and Mamaine Paget – beautiful, gifted English twins whose lives were linked by friendship and marriage to a bohemian world of mid-century writers and intellectuals – the difficulty arises because its author is a relative by accident, a friend by choice, and the namesake of my daughter.

In defence of this unwarranted critical entanglement, it should be noted that Ariane Bankes is herself daughter and niece of the subjects of her dual memoir. Her effort proves that, when it comes to life-writing, affectionate proximity can cast no less light than objective remove.

Nor could the The Quality of Love have been written by an outsider. It was to Ariane that Celia Paget drip fed stories over decades about a glamorous aunt who had died before she was born. And when she herself died it was to her daughter that an old trunk, bulging with diaries, letters, photos and keepsakes was bequeathed, along with permission to tell the story that Celia was too modest or discrete to tell herself.

That story would not pass muster as fiction: the Paget twins’ lives were too gilded, on one hand, their sufferings too unbearable on the other. They were born in 1916 and lost their mother one week later from complications following the difficult birth. After an idyllic childhood in rural Suffolk, they were definitively orphaned at 12, when their father died as well.

Raised in boarding schools and then by a fabulously rich but tyrannical uncle, the identical twins relied on each other to a profound degree. In their favour was quick intelligence, shared talents for music, writing and friendship, and beauty all the more electrifying for being doubled. Against them was the fact that they were women in a pre-feminist world.

Their struggle for autonomy was a triumph of sorts, given the forces arrayed against them. But it was often won by dint of the grace of men whom they married or befriended. Having cut a swathe through society as debutantes in the mid 1930s, the tenuously educated yet fiercely autodidactic pair were drawn to creative types, the bright young things of the generation of Evelyn Waugh and Jessica Mitford – first among whom was Mamaine’s early love, Dick Wyndham, a raffish, twice married privileged bohemian who never fully recovered from the experience of the Great War.

While Cecile, taken up by friends of Dick’s such a Cyril Connolly and Stephen Spender, became involved with London’s interwar literary scene, Mamaine conducted a long-range affair with Dick, who soon returned to the military in preparation for the conflict to come.

Wartime shattered the old certainties. The twins nursed together, Celia contracted a brief and unfortunate “Blitz marriage” to a much older Irish playwright, and Mamaine ended up working for Britain’s wartime propaganda effort at the Ministry of Economic Warfare. It was only after the end of hostilities that she met Arthur Koestler, the man she was eventually to marry.

Post-war life saw Mamaine and the great anti-communist writer move to a farmhouse in Wales, while Celia shifted to Paris, having turned down a proposal of marriage from her dear friend George Orwell and extricated herself from an affair with the philosopher A.J. Ayer. Yet the correspondence between the two remained, in Bankes’ words, “the backbone of their lives, the repository of their thoughts and feelings, and it steeled them both for the tougher times they encountered”.

The tougher times included a difficult relationship for Mamaine. Koestler may have been brilliant, but he was also a heavy drinker and a neurotic, controlling personality. A brief affair with French Algerian writer Albert Camus promised the possibility of happiness and the children that Koestler denied her, but she remained devoted to Koestler until their final separation in the early 1950s.

Celia also struggled to find love and a place for herself. It was only on the verge of Mamaine’s death in 1954 (the pair were both lifelong asthma sufferers; Mamaine succumbed to heart failure as a result of hers) that she married once more and began a family, though Bankes grew up increasingly aware that her mother had lost “part of herself” with Mamaine’s passing, one “that was integral to her being”.

What should be a tragic story, though, is not. “She was made for life,” wrote a stricken Camus to Celia of Mamaine – and Bankes shows us that both sisters were. Despite the testing men each woman encountered and adored, and contrary to current biographical approaches, Bankes asserts her mother and aunt were not victims, rather they looked past “entrenched human failings in favour of the bigger picture”.

And while Celia never fully recovered from the grief of losing her beloved twin, Bankes’ efforts here, using that “talismanic” trunk to rescue an aunt she never knew, braids once again the lives of the Paget sisters – and after decades in which they existed at the edges of biographies devoted to the men they knew and loved, The Quality of Love offers them a centrality which is richly deserved.

Geordie Williamson has been chief literary critic of The Australian since 2008.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout