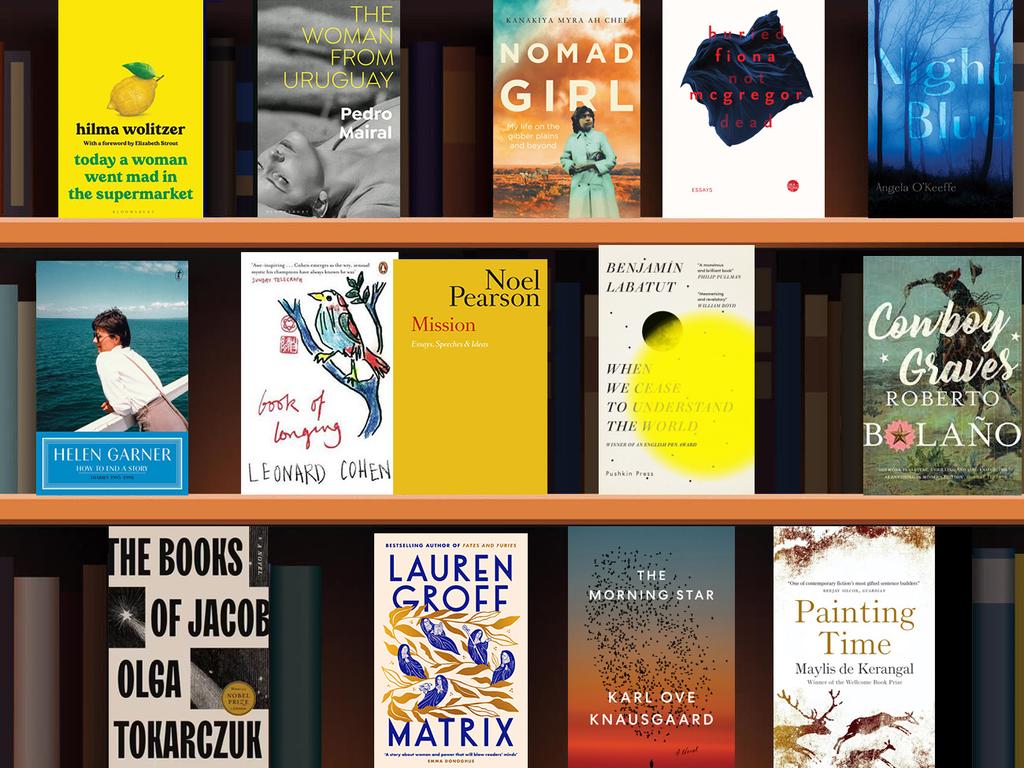

Geordie Williamson’s books to look out for in 2022

Chief literary critic Geordie Williamson presents new works by the best writers, both here and overseas, to add to your reading pile in the coming year.

If 2021 was a fine year for books, it was a challenging one for publishers and booksellers. Rolling lockdowns were followed by global supply chain issues and logistics headaches locally. Only in recent weeks have books started landing as they usually would: en masse, on time, on shelves in bricks and mortar shops or online fulfilment centres, for you, dear readers, to buy.

What has not changed is an industry-wide determination to find the best writers on the best subjects, both here and overseas, and bring them to the public. Even in the deepest and darkest of this year’s lockdowns, timely non-fiction projects or brilliant fictions were being commissioned, writers knuckled down to their edits, and bookshop buyers honed their lists.

The proof is in the sheer profusion and variety of titles on offer for 2022. May this New Year guide aid your reading through a brighter and less challenging year – though with the proviso that it is shamefully partial, necessarily speculative, and idiosyncratic.

Apologies in advance to those authors whose masterpiece I’ve missed.

-

Australian Fiction

■ Robert Lukins’s compelling debut The Everlasting Sunday got plenty of people talking when it was published in 2018. In March he returns with a second novel, Loveland (A&U), a family drama set between the 1950s and the present day. Any writer who can get Michelle de Kretser and David Malouf excited is worth taking notice of.

■ Pulitzer Prize-winner Geraldine Brooks has long been one of the big guns of Australian lit, a reliably brilliant and restlessly curious author.

Horse (June, Hachette) is her first novel in half a decade – an account of racial injustice across American history, from pre-Civil War Kentucky to our current moment of reckoning – drawing on the hidden histories of black horsemen in the antebellum South.

■ Another superb Australian novelist who uses history to his own creative ends is Stephen Carroll. The final volume of his quartet of novels loosely based on the life of poet T.S. Eliot and his first wife, Goodnight, Vivienne, Goodnight (March, HarperCollins) imagines a more fitting end for a clever, damaged woman who was committed to an insane asylum at the age of 50.

■ If there is a highlight among these publishing highlights, it must be Alexis Wright. Her first new fiction since 2013’s The Swan Book is slated for October next year. I can only imagine that Praiseworthy (Giramondo) will be just as formally inventive, incendiary in implication, and driven by the same wild grace as its predecessors.

■ I would be just as excited about the next novel on the list – the first of Fiona McGregor’s diptych of fictions about a real-life underworld figure from 1930s Sydney, Iris Webber – but I commissioned the book for Picador and so must recuse myself from further praise. This much I can say: Iris (Pan Macmillan) is the product of a magnificent obsession. Brace yourself for the result.

■ In 2016, Sean Rabin published Wood Green, a claustrophobic portrait of literary ambition and small-town life set on Hobart’s forested mountain fringe. This year sees an exciting new work by him, The Good Captain, coming via Transit Lounge. That small but perfectly formed Melbourne publisher will also grace us with poet-turned-novelist Philip Salom’s new one, Sweeney and the Bicycles in November. Salom is an author who keeps surprising with each new book. Meanwhile, editor and author Angela Meyer’s Moon Sugar had me at the title. Transit lounge will be publishing her ghost haunted thriller next October.

■ Another great Indie outfit is Affirm Press. In March the firm will have quite the coup: a debut fiction by poet Omar Sakr. Sakr is a talent and a firebrand; his account of a young Muslim man growing up queer in Western Sydney, Son of Sin, will surely be one of the year’s most talked-about titles.

■Yumna Kassab is not an author I was familiar with, but her second novel (or collection of interconnected stories) Australiana (Ultimo Press, April) sounds intriguing – a map of small town life drawn by human imagination rather than Google Streetview.

■ Anyone who has read Craig Sherborne’s memoir Hoi Polloi will know him to be a flat-out genius. But Sherborne’s fictions are equally good. His new novel The Grass Hotel (Text, February) takes the form of a monologue spoken by an elderly woman with dementia to her son. Prepare for a beautiful and remorseless investigation of one family’s secrets.

■ And if you need a laugh slightly less bitter than Sherborne’s, look no further than Toni Jordan and her new novel – Dinner with the Schnabels, out in April from Hachette. Jordan has a track record of impossible poise. She is a writer of acute intelligence who is wisecrack witty, yet tender as a kindly aunt.

■ The only Australian writer to match Jordan for comic elan is also back this year. I mean Steve Toltz, he of A Fraction of the Whole – whose new effort, Here Goes Nothing (PRH, May) is narrated by a dead man who is obliged to watch as his widow enters a relationship with his killer. It will be fascinating to see how Toltz wrings humour out of that set-up.

■ Finally, an unashamed cheat. A World with No Shore (February) is a novel written by a Frenchwoman named Helen Gaudy and set in the Arctic in the 1930s. But Black Inc.’s edition of the work is translated by Stephanie Smee, an Australian who is rapidly becoming the go-to person for both classic and cutting-edge writing from Europe.

-

International Fiction

■ Hanya Yanigahara’s second novel A Little Life was an extraordinary success, given its scarifying subject matter relating to child sexual abuse. By all accounts her new book, To Paradise (Picador, January) – a work that links three narratives from past to future in an alternative America – manages, once again, to marry tenderness and savagery in a manner from which readers cannot tear their gaze.

■ Violeta (January, Bloomsbury) is the new novel by that indomitable grand dame of Latin American literature, Isabel Allende. Her story, of a 100-year-old woman who has lived through a century of unprecedented drama and flux, will doubtless find a home on a million bookshelves.

■ Fans of American author Sheila Heti will be in for a treat this February, when her new novel, Pure Colour lands via Harvil Secker. This “galaxy of a novel” sounds like nothing less than a mystical tract for a secular age.

■ Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond was the very first book I published at Picador, an effort closer to being a tribute to genius than a practical business decision. That debut collection of short autofictions garnered the kind of critical adulation that most writers can only dream of. Word is that Checkout 19 (August, Jonathan Cape), her first novel, is on a whole new level again. Watch for it on the Booker Prize list next year.

■ Meanwhile, Jennifer Egan is the rare author who can match Bennett for cultish reverence. In The Candy House (Scribner, April), the Pulitzer-winning author of A Visit from the Goon Squad creates a companion fiction for the earlier novel, incorporating characters from its pages. Its story of a man who creates a digital empire out of a discovery that allows people to download their unconscious and search and share every memory from it, sounds terrifyingly apt for our social media-saturated moment.

■ You may have noticed that Emily St John Mandel’s post-apocalyptic tale of a travelling Shakespeare troupe, Station Eleven, is about to hit your small screens. Sea of Tranquility (Picador, April) promises to be another elegant appropriation of speculative fiction tropes for literary ends.

■ Monica Ali, author of the wildly successful Brick Lane, has been off the radar for a while. Love Marriage (Scribner, January) promises to change all that. Ali’s account of a daughter of Indian migrants attempting to navigate cross cultural relationships in present-day London has all the ingredients of a hit.

■ Speaking of hits, Booker Prize winner Marlon James shook the publishing world when it was revealed that he was writing a fantasy series – a black retort to genre dominated by white authors. Moon Witch Spider King (February, PRH) is the second volume of his Dark Star Trilogy. It’s told from the perspective of the witch who served as the hero’s adversary in the first book of the series.

■ A very different book indeed is Elizabeth Finch (PRH, April), Julian Barnes’ newest fictional outing. Barnes has been going from strength to strength in recent years, so this new novel, which the publisher describes as “balm for our times”, sounds promising.

■ Mohsin Hamsid, Pakistani author of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, is not so emollient with his new one. The Last White Man (PRH, August) a modern fable of race in which white people across the world find themselves turning black. Nothing less, it sounds, than a reimagining of our collective future.

■ Alexander Maksik is one of the most talented and versatile novelists of his generation. 2013’s A Marker to Measure Drift, about a young Liberian woman who flees Charles Taylor’s regimen only to find herself adrift among holidaying westerners on Santorini, is a novel that keeps haunting its readers. His latest, The Long Corner (Europa Press, May), sees a disenchanted writer from New York invited to an artist’s colony on a tropical island. What seems at first like an idyll from the politics of Trump’s America turns into its own kind of nightmare.

■ Jennifer Pinkerton’s Heartland (A&U, March) takes that most primal of human drives, the urge to find a mate, and explores it through the prism of new technologies and the evolving relationships such change has driven. Told with empathy and unblinking clarity, via interviews, memoir and reportage, Pinkerton is the ideal Virgil to guide us through the weird phenomenon of dating in the digital age.

-

Australian Non-Fiction

“Why”, asked Eliza Reilly, in Sheilas - the groundbreaking web series co-created with her sister Hannah - “is Australian history such a goddam sausage party?” Reilly’s eponymously titled book, due out in February from Pan Macmillan, aims to recover the stories of those unsung women who shaped our modern nation. Eliza’s prose is bouyant with wit, but her research is rock-solid and her underlying intentions - to bring a feminist reconsideration of our history to a broad public - in deadly earnest.

■ Elsewhere at Allen & Unwin, astronomer Duane Hamacher, with the generous assistance of Elders and knowledge holders, introduces us to the world of Indigenous knowledge of the heavens. The First Astronomers (March) promises to be the kind of book that enlarges, once again, our sense of wonder at the scope and complexity of First Nations’ understanding of the world through which they moved prior to 1788.

■ Melbourne’s Black Inc. has always been excellent at publishing around science, history, and current affairs, and 2022 is no exception. Growing up in Country Australia (April) is the latest in a string of anthologies in the same vein. Given that Rick Morton (whose memoir of a Top End childhood in A Hundred Years of Dirt was an instant classic) is editor here, trust that you’re going to get a feast of fine and confronting contributions.

■ Later in the year, another star journo of the Schwartz media ecosystem, David Marr, will turn his attentions to colonial violence on these shores with A Family Business. His publisher is giving little away on the subject matter, but given Marr is incapable of writing a dull sentence, I don’t doubt it will electrify.

■ Finally, that same firm turns its attention in September to the main game – that of human survival. Joelle Gergis’s Witnessing the Unthinkable is a book by a prize-winning climate scientist that describes the efforts of her peers to do nothing less than save our world from the effects of runaway climate disruption.

■Still, the work oriented towards the natural world and our place in it that I most look forward to belongs to a novelist. Terri-ann White’s new imprint Upswell has nabbed Gregory Day’s collection of place-based writings, Words are Eagles (July). Day has spent decades notating the landscape, people, and Indigenous languages of his corner of the southwest Victorian coast. His essays grapple with a simple yet enormous question: how do we celebrate through art, or even properly dwell, in places from which others have been dispossessed?

■ Another major Australian writer to traverse similar ground is Kim Mahood. Wandering with Intent (Scribe, October) are essays based upon the Top End-raised Mahood’s journeys in some of the most remote parts of this country. Mahood has proven to be an adroit and thoughtful diplomat for relations between black and white worlds in Australia; this collection will only burnish that role.

■ One “life” and one biography devoted to fascinating Australian women writers are set to appear this year. The first is from Transit Lounge in July with Telltale: Reading, writing, remembering by Carmel Bird. Bird is a smart and talented veteran of Australian literature and doubtless her memoir, concerned with the ways in which we are shaped by books, will be a social as much as a literary account.

■ The biography is for Katherine Susannah Pritchard, that pioneering author and activist from Western Australia. Titled The Red Witch, Nathan Hobby (MUP) has obviously elected to explore the author’s political radicalism – Pritchard’s notorious communism a stance that would see the writer at odds with both her class and her society.

■ Academic Julieanne Schultz is a pioneer in her own right: the founding editor of garlanded quarterly Griffith Review. Her new book for Allen & Unwin, The Idea of Australia: Searching for the soul of a nation (March), has a distinctly Russel Ward vibe. Ward’s classic 1958 history The Australian Legend asserted that we were an essentially egalitarian society. One suspects that, two decades into the new century, Schultz may have a different take.

■ Regarding a finger on the nation’s pulse, keep an eye out for three new short titles from the In the National Interest series from Monash University Publishing. The first half of 2022 sees essays from Jo Dyer, Gareth Evans and Richard Dennis in the coming months, each devoted to the author’s particular hobbyhorse.

■ Finally, NewSouth will, next November, be publishing a book whose premise is extraordinary. In Boundary Crossers: The untold story of Australia’s other bushrangers, Meg Foster explores cases of Aboriginal, Chinese, African-American, and female bushrangers. History, once again, proves itself to be more extravagant than any fiction.

-

International Non-Fiction

If, like me, you have managed to live in profound ignorance of Africa’s national variousness, 2022 brings Chinny Ukata and Astrid Madimba’s It’s A Continent (Coronet, May). It’s an atlas of essays dedicated to each nation of that vibrant, benighted, and complex continent; a project grown out of the historians’ hit podcast.

■ In the Margins (Europa, March) sees the notoriously private Italian author Ellena Ferrante release a book of essays about her life as a writer. Doubtless the pieces will, like her celebrated fiction, be stiletto sharp. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, an equally piercing intelligence is at work in Burning Questions (PRH, March), in which Margaret Atwood collects essays, reviews, speeches and occasional pieces from the last two decades of her career.

■ One last critical work: Last Days of Roger Federer sees the welcome return of Geoff Dyer, with a book concerned with late style and last things. It’s a project that sounds such fun and so gloriously off-kilter that I quote its synopsis in full: “With a playful charm and penetrating intelligence, he examines Friedrich Nietzsche’s breakdown in Turin, Bob Dylan’s reinventions of old songs, JW Turner’s paintings of abstracted light, John Coltrane’s cosmic melodies, Jean Rhys’ return from the dead (while still alive) and Beethoven’s final quartets – and considers the intensifications and modifications of experience that come when an ending is within sight. Oh, and there’s stuff about Roger Federer and tennis too.”

■ Jan Morris, that British (she’d say Welsh) national treasure, died in 2020. Life from Both Sides (Scribe, September) by Paul Clements is a biography that seeks to draw together the multiple strands of the author’s life. From her first half-century as a man named James Morris – author of the standard history of the British Empire and, as a foreign correspondent, the first journalist to report back on Hillary and Tensing’s conquest of Everest – to the woman named Jan Morris who became the most beloved travel writer of her generation. A life well and fully and bravely lived.

■ Morris’s life will be joined by that of another national treasure next Spring. The Alan Rickman Diaries (Canongate, September) is compiled from 27 gossipy and candid diaries covering more than a quarter of a century left at the great and glorious actor’s death.

■ There is always something fascinating about touching the hem of a genius.

In Novelist as a Vocation (PRH), by Nobel prize-winner Haruki Murakami, the author has reworked a series of essays first published in Japan’s Monkey magazine about the craft of writing and the role of the author for a global audience.

■ Carlo Rovelli became an unlikely bestseller with last year’s meditation on the young Werner Heisenberg and quantum theory in Helgoland. This year sees publication of There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness: And Other Thoughts on Physics, Philosophy and the World (PRH, November), articles assembled from Italian newspapers in which the theoretical physicist explores everything from Vladimir Nabokov’s butterflies to Octopus’s intelligence.

■ Finally, February next year sees publication of a book that deeply intrigues me. Stalin’s Library (Yale) by historian Geoffrey Roberts takes a deep dive into the dictator’s huge personal library, assembled over many years and heavily annotated, in order to create a portrait of a divided man: an ideologically rigid ruler who nonetheless read everything and everyone in order to know his enemies better.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout