The gifts that keep on giving

The Art Gallery of NSW’s latest acquistion, a polychrome wooden figure by Pedro di Mena, represents Saint Francis absorbed in meditation on a crucifix he holds tenderly in his hands.

James Fairfax (1933-2017) was the last to lead the newspaper empire his family had founded 1½ centuries earlier, until the crisis of 1987, when his half-brother Warwick made a disastrous attempt at buyout and privatisation that ultimately led to the ignominious takeover of The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian Financial Review by Nine Entertainment.

But Fairfax was also a lifelong and discerning collector, and in later years a generous donor whose gifts enriched many public art galleries in Australia, while his country home in Bowral, Retford Park is now a National Trust house museum. Fairfax’s gifts to the Art Gallery of NSW – especially from 1991 to 1999 – were published in an exemplary scholarly catalogue by Richard Beresford and Peter Raissis in 2003, The James Fairfax Collection of Old Master Paintings, Drawings and Prints.

When Fairfax died, the gallery published an acknowledgment, reading in part: “Over the decades he enriched the gallery’s own holding through donating a magnificent array of works by artists including Tiepolo, Rubens, Ingres, Canaletto and Watteau, and our 15th-19th century European galleries bear his name.” Yet the importance of these donations to the AGNSW was even greater than may appear at first sight. At the end of Alexander Edward Gilly’s fascinating new book James Fairfax: Portrait of a Collector in Eleven Objects, the former director of the gallery, Edmund Capon, admits that Fairfax’s gifts effectively reoriented collecting policy and thus had a catalytic or indeed multiplier effect on this part of the gallery’s holdings.

Capon admitted to Gilly in 2014 that when he became director in 1978, the gallery’s collection of European art before 1800 was so patchy that he felt there was nothing to be done. But the Fairfax gifts “gave a completely new impetus to the whole area … James actually determined the policy of the gallery. Because the significance of his gift was such that it gave us a foundation to build upon. He was mainly 18th century, so I added 16th and 17th centuries, maybe half a dozen. Major things like the Bronzino, the Procaccini. We did the 17th-century gallery and James did the 18th-century gallery … Had it not been for James’ gift, I wouldn’t have bothered.”

Fairfax’s gifts in fact extended well beyond the 18th century and include the beautiful 15th-century Sano di Pietro Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome, John the Baptist, Bernardino and Bartholomew (given by John Fairfax & Sons in 1971), several important 16th-century paintings, and 17th-century masterpieces by Jacob van Ruisdael (1991), Claude Lorrain (1992) and Peter Paul Rubens (1993). What is important, though, is that they were exemplary in creating a new sense of momentum and purpose, and in establishing the environment in which further works could be acquired to build a richer, deeper and more diverse Old Master collection. And this momentum has to some extent survived even the dreary reign of Capon’s successor as director, who at last has announced his intention to leave.

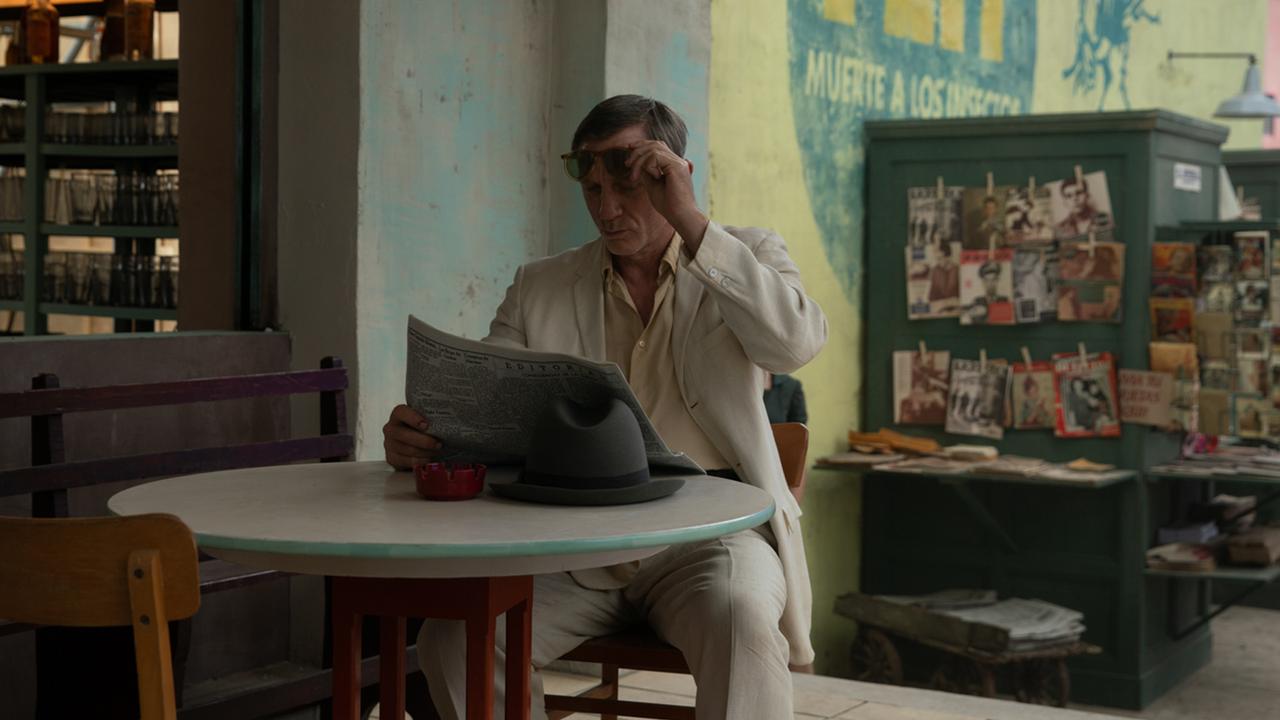

The gallery has received further gifts from benefactors, including Kenneth Reed, and has been able to make a few significant purchases in the early modern period, such as a large majolica plate illustrating the Sack of Rome (1530, purchased 2011) and Jusepe de Ribera’s painting of Aesop (1625-31, purchased 2021); I wrote about this acquisition and the beggar-philosopher subgenre in this column on May 7-8, 2022.

Ribera is best known as a dominant figure in Neapolitan painting in the 17th century, but Naples was a Spanish possession at the time and the artist was originally from Spain. This acquisition thus opened another direction for collecting, in the distinctly dark and intense Spanish-Neapolitan cultural environment of the baroque age. And this has indeed been the context for two further significant acquisitions this year.

One of these is a fine still life of apples and pears by Juan de Zurbaran, one of the greatest Spanish masters of the 17th century after Diego Velazquez himself (partly funded by the James Fairfax Foundation), whose simplicity and sober presence complement the fine but more elaborate Dutch “breakfast piece” still life attributed to Gerrit Williamsz Heda – a painting that was cleaned and identified only a couple of years ago after hanging for years in a National Trust property; coincidentally both house and painting had belonged to another member of the Fairfax family in the 19th century.

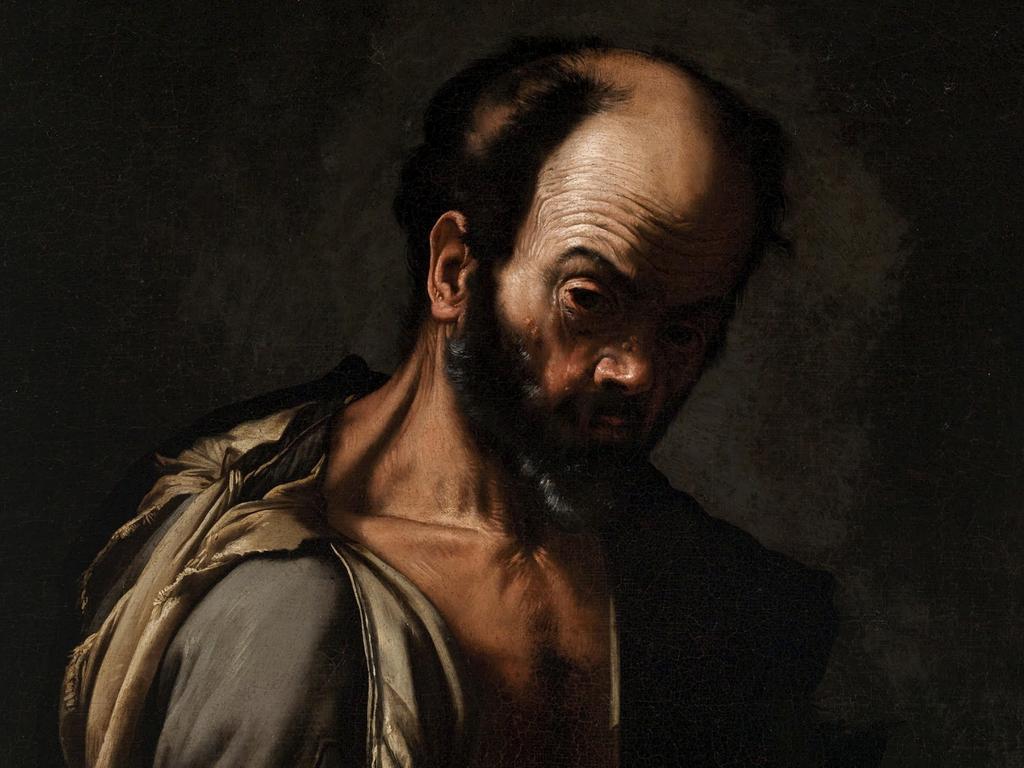

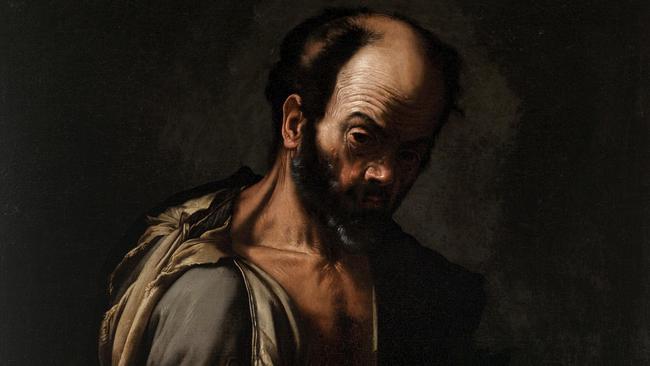

The other new acquisition is an extraordinary polychrome wooden figure by Pedro de Mena, representing St Francis of Assisi absorbed in meditation on a crucifix he holds tenderly in his hands. The features and expression of the saint are rendered with exquisite refinement and expressiveness, the brow furrowed and the eyelids heavy as Francis imagines the suffering of the crucifixion, his lips parted as though to hint at a sigh of compassion. Details of flesh, hair and beard are treated with astonishing naturalism, and even the coarse texture of the Franciscan habit is conveyed by painstaking carving as well as painting.

Highly naturalistic polychrome sculpture had precedents in Renaissance art – as in Donatello’s portrait of Niccolo da Uzzano (1430s) but by the 17th century, and as a form of religious art, it was distinctively Spanish. Several years ago the National Gallery in London held an important survey of these works – largely unfamiliar to most viewers and often overlooked by art historians – The Sacred Made Real (2009-10), which I reviewed in this column in January 2010; anyone interested in reading this article can still find it online.

As I pointed out then, one only has to compare the Spanish polychrome works to even the most ecstatically religious sculpture produced in Italy, such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa (1647-52), made a quarter of a century before the St Francis (signed and dated 1677), to realise how very much more abstract the marble carving is, for all its attempts at dramatic illusionism and the brilliance with which Bernini has differentiated the textures of the angel’s diaphanous gown and the saint’s heavy woollen habit.

The differences are readily apparent, yet they are even more profound when we reflect on the way these wooden figures were made. The process is well-described in Raissis’s catalogue entry on the AGNSW website, but for further detail and illustrations of a fascinating and elaborate art form it is worth watching a video produced by the Getty Museum that easily can be found on YouTube by searching “Making a Spanish polychrome sculpture”.

The process has little in common with the standard way a carver approaches a block of stone, cutting in from all sides to produce or, as Michelangelo imagined, to reveal the desired form. These works are not solid but constructed around a boxlike inner armature to which surface panels are attached. There are sound reasons for this process: wood does not come in large blocks as marble does and the very fine-grained woods used for the most important parts of the figure, the face and hands, may be valuable and available only in small blocks.

But this means that the figure, despite its extraordinary surface naturalism, does not have the deep sense of inner substance, weight and life that can animate even a far less illusionistic stone sculpture. It is more like a theatrical mask, as Raissis hints in his catalogue text: for the face is hollow like a mask, and the glass eyes and ivory teeth are set into it from behind, before it is attached to the core structure.

And what of the famous “paragone”, the comparison of painting and sculpture that arose out of the personal rivalry of Leonardo and Michelangelo? The partisans of sculpture claimed that painting offered merely a two-dimensional picture, while sculpture produced three-dimensional simulacra; but the painters replied that a white marble figure was lifeless, and painters could imitate the quintessential colours of life.

The debate arose in the 16th century, but it is in the 17th century that we can see its effects most clearly: if Rubens seems obsessed with the subtle hues of flesh, the lustre of hair and beards, or the moisture of an eye, it is because these things signify life; and if Bernini loves not only movement but parted lips, it is because, mindful of the charges levelled against his art, he seeks to evoke the effect of breath.

In this perspective, the obvious conclusion is to think of polychrome sculpture – which, as we have seen, exploits all the illusory effects of colour yet also seeks to express breath itself – as a combination of painting and sculpture. Because of their lack of properly sculptural presence, however – because of that sense that they are hollow theatrical props – it is almost more appropriate to think of them as three-dimensional paintings; except that unlike paintings the figures are not surrounded by light and atmosphere and set in an imaginary space.

In any case, there is no denying the extraordinary skill of both the builder and carver on the one hand, and the painter of flesh (encarnaciones) and costume (estofado) on the other. And what makes de Mena so exceptional is that he executed both parts of the process himself or with the members of his workshop.

As for the subject, St Francis has been since his lifetime in the 13th century one of the most universally beloved saints, venerated for his spirituality, his selfless humility and his love of his fellow man, of animals and of the natural world in general. It is remarkable that the order he founded became, with the Dominicans, one of the two greatest of the high medieval world: indeed the biggest churches in most Italian cities tend to belong to these orders.

According to legend, when Pope Nicholas V opened the tomb of Francis in the mid-15th century, he found the body of the saint standing upright, uncorrupted, gazing up at heaven. It was in this way that de Mena represented him as a full-scale sculpture in Toledo Cathedral. Here, though, it is as though he has adapted Francis’s well-known adoration of the crucified Christ – he is often shown receiving the stigmata – to a more contemporary Jesuit sense of spirituality.

The Jesuits had been founded more than a century earlier by the Spanish St Ignatius of Loyola, who had conceived the idea of forming an army of Christ to lead the religious struggle that we now know as the Counter-Reformation. In personal spirituality, however, Ignatius enjoined meditation and composed a series of Spiritual Exercises (drafted 1522-24, published 1548).

Among the recommended objects of meditation were the various episodes of Christ’s life, and especially the Passion; and this seems to be the inspiration for de Mena’s work. Intensely religious as the sculpture is, it does not illustrate a miraculous event such as the receiving of the stigmata but invites us to join Francis in his contemplation of the suffering that was the price of redemption.

St Francis of Assisi (1677) by Pedro de Mena

New acquisition, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney