The Fierce Country: Stephen Orr on Australia’s unsettled heart

The Fierce Country is an episodic gathering of true stories from Australia’s unsettled heart.

True stories of children lost in the bush, and the imaginative embellishments of them, constitute one of the core bodies of Australian narrative since European settlement. This has, and continues to be, “the country of lost children”. It also might be described as “the land of unmarked graves”.

In The Fierce Country, an episodic gathering of “true stories from Australia’s unsettled heart, 1830 to today”, novelist Stephen Orr takes his title from Douglas Stewart’s poem The Birdsville Track: “Three hundred miles from Birdsville to Marree / Man makes his mark across a fierce country.” Or vanishes without trace.

The landscape Orr describes holds “no malice, but neither pity”. What he traces across a wide historical and geographical compass is “the friction between man, woman, child and landscape”; “stories of lost children, murder and wrong turnings”.

Those stories begin with conflict between European and Aboriginal Australians. The first cluster ranges from lieutenant governor George Arthur’s “Black Line” of 1830 in Van Diemen’s Land, a failed roundup of Aborigines that nevertheless did not long precede their concentration and near destruction.

Still in that decade are the Myall Creek massacre (for which eight white perpetrators were hanged) and the ambiguous story of Eliza Fraser. Then Orr jumps to Daisy Bates in eccentric retirement in Adelaide and her 1938 book The Passing of the Aborigines. He offhandedly calls her a “bigamist” without mentioning that her first husband was Harry “Breaker” Morant.

This group of stories indicates the abiding structural problem of the book. Albeit in chronological order, with some stories more familiar than others, this is one tale after another, with no more of a unifying thesis than is suggested by the title metaphor.

Anachronistically, this material might have been better suited to one of those weekly radio serials of the first decades after World War II.

Orr has enthusiastically worked up a varied series of case studies, beginning with the Point Puer prison for boys near Port Arthur in 1834-49 (the source of a shocking passage in Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of His Natural Life), before cutting to 1894 and the other side of the continent, from the Tasman Peninsula to the Kimberley.

His next story is about the proclaimed Aboriginal outlaw and legendary resistance fighter Jandamarra, who finally was killed in the Windjana Gorge country.

There is a detour to NSW for the story of Jimmy Governor (Jimmie Blacksmith in Thomas Keneally’s 1972 novel) before Orr concludes: “Jandamarra has become myth. Spirit. The subject of novels, documentaries, a play. A man who tried to live in two worlds.”

None of those works, or their authors, is named in the text or in the index. These are omissions for which there seem to be no particular warrant.

Still at the end of the 19th century, Orr offers the lesser known narrative of the Calvert Scientific Exploring Expedition of 1896-97. Two of its members died of thirst after the party separated, in the Great Sandy Desert, south of Fitzroy Crossing.

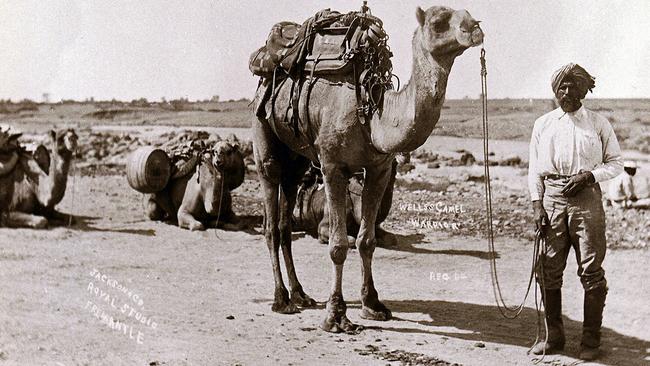

The rest of this “expedition into Australia’s heart of darkness” (the reference is to Joseph Conrad’s novel yet to be, rather than the more notorious local metaphors of “Red Centre” or “Dead Heart”) is saved, largely by the exertions of the team’s Afghan cameleer Dervish Bejah.

In the words of Douglas Stewart’s poem Afghan, Bejah was one “who steered his life by compass and by Koran”. He is seen at prayer in the background in the 1954 film Back of Beyond, about the outback mailman Tom Kruse, who for decades plied the Birdsville Track.

The film is a regular point of reference for Orr’s outback stories, although its Tasmanian director, John Heyer, is not mentioned until the last of them.

One of the most moving and benign tales has the longest span. This is The Tea and Sugar, 1917-96, which concerns the provisions train that ran weekly to fettlers’ settlements along the Trans-Australia Railway between Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. The excitement of the arrival punctuated the isolation of the hardy dwellers on the Nullarbor. Its passing adds to the melancholy accounting of ghost towns and lost traditions that this continent allows.

Orr has more trails to follow: with Lutheran missionary Carl Strehlow and his son to Horseshoe Bend, along the Rabbit Proof Fence in Western Australia where boundary rider and soon-to-be best-selling novelist Arthur Upfield gave an itinerant villain the idea for an undetectable murder, to that great chimera and hoax, Lasseter’s supposed reef of gold (fictionalised first by Upfield) of which Peter Dawson sang: “But what was the end of Lasseter’s quest / And where is the gold to be found?”

A group of stories relates deaths from exposure because of inexperience and overconfidence, such as the five members of the Page family who died in 1963 off the Birdsville Track, or the under-supervised teenage jackaroos Simon Amos and James Annetts.

The Fierce Country is a slim book with rich pickings, ready for every grey nomad’s small bookshelf.

Peter Pierce, who died on September 4 (see A Pair of Ragged Claws), was a gentleman and a scholar.

The Fierce Country

By Stephen Orr

Wakefield Press, 216pp, $27.95