The Carbon Club and The Coal Curse: Regrets? We may have a few

Two new accounts suggest a handful of individuals – most with no scientific qualifications – have made a calculated choice that could have dire consequences for the rest of us.

In his account of the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar observed: “Fere libenter homines id quod volunt credunt” (people willingly believe what they wish). Two important new contributions to the climate change debate agree with Caesar.

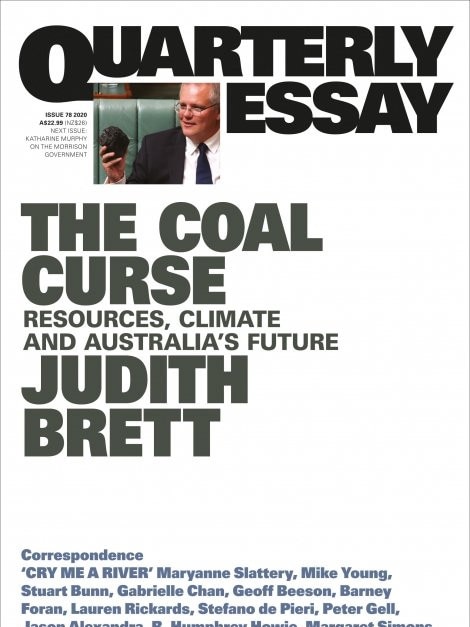

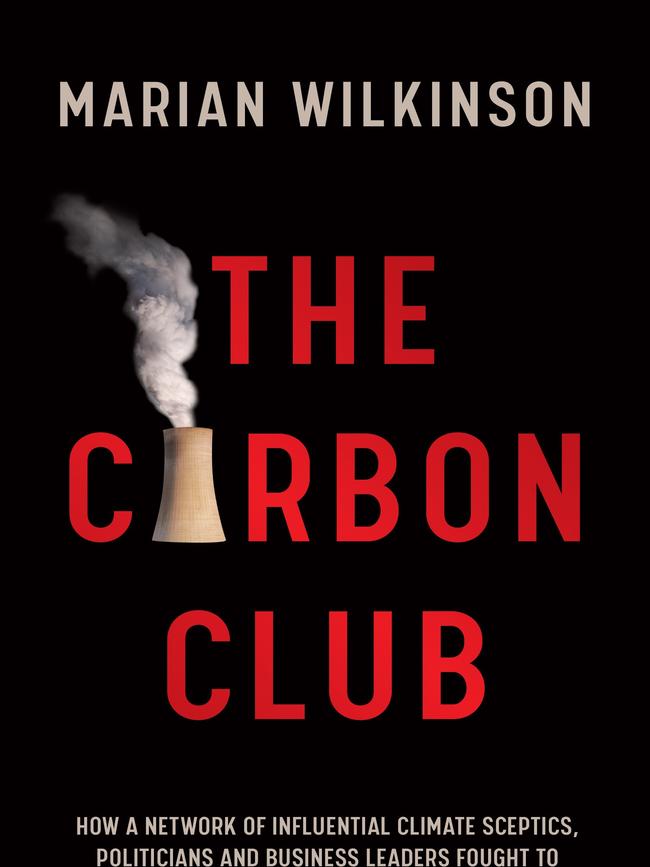

Marian Wilkinson and Judith Brett are among Australia’s most incisive nonfiction writers. In The Carbon Club and The Coal Curse respectively, neither poses as a scientific expert. Each accepts at face value the overwhelming consensus of qualified scientists worldwide: unless greenhouse gas emissions are reduced within the next few decades, the consequences for the Earth’s climate – and human civilisation – will be dire.

True, the exact timing and extent of those consequences are difficult to forecast. As Wilkinson notes, “climate modelling is hugely complex”. And it remains problematic to attribute to global warming any single “extreme weather event”: heatwave, bushfire, drought, cyclone, hurricane, flood, mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef, etc. It is also true that the short to medium-term costs of climate action will be high.

The stakes are enormous. Yet serious, concerted action has still not been taken, notwithstanding the efforts of the UN. Why? Using Australia as a case study, Wilkinson and Brett each proffer the same answer: lazy, venal self-interest.

Wilkinson acknowledges the tiny cohort of dissident scientists who question the consensus. There are a few in every country but, as she explains, perhaps the most significant in Australia was a professor of geology, Robert (Bob) Carter (1942-2016), long-time head of the School of Earth Sciences at James Cook University. Three or four others in Australia have followed Carter’s lead. Wilkinson does not dispute their qualifications, or their “passionate” sincerity.

The scientific method will always throw up mavericks. The vital issue in a liberal democracy is which scientific voices should be believed by people in positions of commercial and legal power.

Wilkinson and Brett argue that in Australia a handful of such individuals – most with no scientific qualifications to speak of – have made a calculated choice to believe the dissidents. The authors name names. Wilkinson’s research is especially thorough. The roll-call is dominated by senior figures in the mining and fossil-fuel industries. Their unofficial leader since the 1980s has been Hugh Morgan, former chief executive of Western Mining Corporation. Gina Rinehart, Australia’s richest person, is one of the few women in the club. Some of them, perhaps, have convinced themselves of the truth of the dissident scientists’ position. Wilkinson concedes as much.

These individuals have controlled powerful lobby groups, courted high-profile mouthpieces in the media, influenced the key finance arm of the Liberal Party (the Cormack Foundation) and variously demonised or lionised politicians of strategic importance.

Their ambition, largely achieved since 1996, is a policy of “no regrets”: Australia should not do anything that undermines our “competitive advantage” in mining and fossil fuels. In truth – and this is Brett’s central theme – Australia has become dangerously over-dependent on export income derived from minerals (our so-called “quarry vision”).

In selling the “no regrets” policy to the general public, it has been essential to promote the views of the few dissident scientists, as well as attack the most prominent mainstream scientists. In Brett’s view, the dissident scientists provide moral cover.

The worst villains are those who, for their own selfish purposes, propagate the dissident scientists’ views while believing them to be false. Even those who may have convinced themselves of the truth of the dissidents’ views should ask themselves two questions. What if I am wrong? Do I have the right to take such colossal risks?

There is no need for me to name the prime ministers, state premiers, party kingmakers and ministers in relevant portfolios who fall into this category. They know who they are. Wilkinson and Brett dissect them all. History may well condemn them – but in most cases posthumously, which is part of the problem.

Perhaps the most morally hollow argument from the “no regrets” school is that because Australia contributes only 1.3 per cent or so of global emissions, we have no duty to do anything (or as little as diplomatically tenable). “It’s up to the US and China!”

The very same people never apply this argument to Australian participation in foreign wars, and generally have been supportive of political leaders in the US who have stymied every global attempt at climate action.

In any event, at 1.3 per cent, Australia is still the 14th biggest emitter (out of 195 countries) and among the worst per capita in the developed world.

It is clear from these books that the two prime ministers best placed to have made a difference were Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull. Their climate policies varied, but both possessed the necessary knowledge, intellect and charisma, and (for a while) high public standing.

Infamously and inexplicably, Rudd squibbed the challenge in April 2010 – and undermined his own hard-won credibility – by dropping his signature policy, the Emissions Trading Scheme.

Turnbull always faced an uphill battle in the Coalition, and Wilkinson lays out the grisly details. But it seems Turnbull effectively surrendered before he even became PM, by agreeing to National Party conditions (still secret) that tied his hands. He tried appeasement, but, as Brett writes, “nothing would satisfy the anti-climateers short of wholehearted commitment to the future of coal”.

Only Julia Gillard implemented a policy that, for two years (July 2012-June 2014), substantially reduced Australia’s emissions: the notorious “carbon tax” legislated in the Clean Energy Act of 2011. But Gillard lacked the gravitas to defend either herself or her policy against vicious attacks from the carbon club. Likewise Bill Shorten.

The authors agree that in response to COVID-19 Australia’s political leaders have acted, by and large, as conscientious stewards of the broader public interest. Any errors have been the result of honest misjudgment or negligence, not (as in the US) shameless disregard of mainstream science and human life.

But when it comes to climate change it has been, and remains, much different.

Roy Williams is a Sydney-based lawyer and author

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout