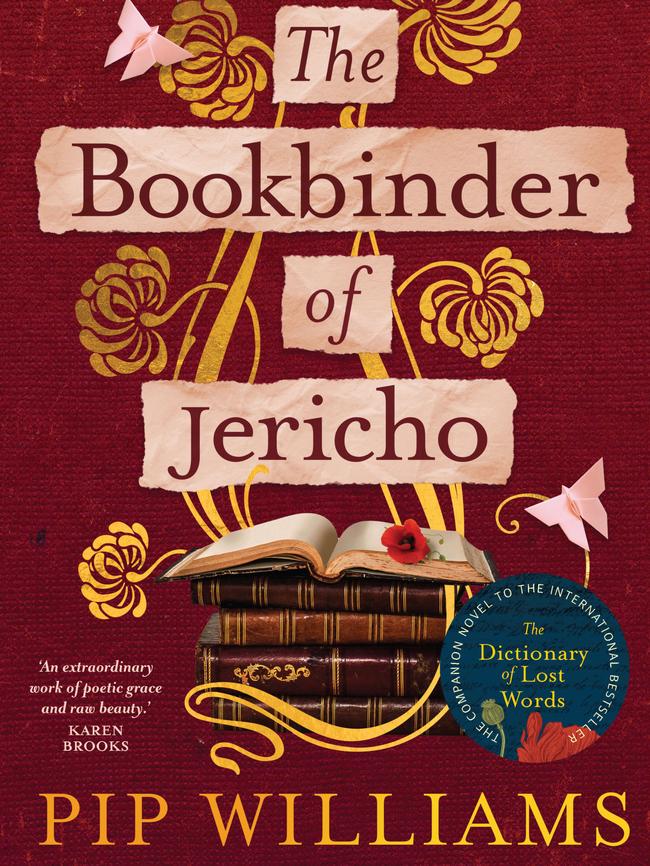

The Bookbinder of Jericho book review: timely sequel is a subversive delight

The Bookbinder of Jericho, like its predecessor, blends fact and fiction. Like all good historical novels, it has a timeliness that makes it relevant today.

While it’s wise not to judge a book by its cover, that doesn’t mean its facade is trivial. Nor is the rest of the physical anatomy of a book, whether the words inside be by Hilary Mantel or Harold Robbins.

“Reading was such a quiet activity and the reader …” thinks Peggy Jones (the unquiet protagonist of Pip Williams’ charming, thought-provoking historical novel The Bookbinder of Jericho) “ … would never imagine all the hands their book had been through, all the folding and cutting and beating it had endured. They would never guess how noisy and smelly the life of that book had been before it was put in their hands.”

It is July 1914 and 20-year-old Peggy works in the bindery of Oxford University Press in Jericho, the Oxford neighbourhood the publisher made its home in 1830.

Her job is to use her bone folder, passed on from her mother, to fold the pages of books ahead of their binding. We first meet her taming The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.

She sneak-reads a line in the editor’s preface – “I have only ventured to deviate where it seemed to me …” – and it plants a seed in her mind, or waters a seed that was already there.

She finds its continuation on the next page, which is being folded by another of the 50 “bindery girls – the youngest twelve, the oldest beyond sixty”.

Her supervisor, Mrs Hogg, sees what she is doing and admonishes her. “Your job is to bind the books, not read them.”

This reprimand sums up the world the intelligent, ambitious Peggy yearns to escape. Not only is she “Town” (working class) rather than “Gown” (academic) but she is a woman.

“I imagined spending my days reading books instead of binding them.” Instead “we were just part of the machinery that printed their ideas and stocked their libraries”. “Their”, in a nutshell, means men. This book is a companion to Williams’ 2020 bestseller The Dictionary of Lost Words, in which Esme Nicoll, daughter of a lexicographer, preserves words, mostly ones relating to women, that are being omitted from the inaugural Oxford English Dictionary.

Chronologically it is an overlap and a sequel and some of the original characters, including Esme, make cameo appearances. The one with more than a cameo is Esme’s irrepressible actor friend, Tilda, who, now 35, is only offered roles as a “nanny” or “old whore”.

Tilda is a mentor to Peggy and her twin sister Maude, who is an intriguing character. Content to work at the bindery, she goes about life with a simplicity and honesty that makes people think she is a bit simple, but she is not.

“She understood, I think,’’ Peggy reflects, “that most of what people said was meaningless.”

Peggy and Maude live on a narrowboat named after Calliope, the muse of poetry in Greek mythology. The name was chosen, almost as a protest symbol, by their late mother.

It is not lost on Peggy that Calliope’s “place” was to inspire stories, not write them.

Women’s suffrage, central to the first book, remains important, but is overtaken by the outbreak of World War I.

Peggy’s desire to “bloody deviate” is helped and hindered by the conflict.

The German invasion of Belgium brings Belgian refugees to Oxford, one of whom, Lotte, a librarian, joins the bindery and befriends Maude.

Soon afterwards Oxford’s Somerville College becomes a hospital for wounded Allied soldiers and here Peggy meets a Belgian officer, Bastian, his face swathed in bandages like the “invisible man”. They become friendly.

Whether that friendship can become something more depends on factors beyond Peggy’s remit. She wants to go to university, to don a gown. But is being a scholar, wife and mother a realistic – or even possible – choice in the early 20th century?

This novel, like its predecessor, blends fact and fiction. Like all good historical novels, it has a timeliness that makes it relevant today.

As the war that some thought would be over in weeks drags on, the English response to the Belgian refugees has similarities to what is happening now in Europe, including in Germany, to Ukrainians seeking refuge from their war-torn land.

And as I read of Peggy’s struggle to be respected for her mind, rather than what she can bind, I thought of girls being excluded from education in today’s Afghanistan.

The author is a lover of the written word and how it is presented.

With that in mind, let’s finish with a beautiful moment between Peggy and Ebenezer, the old gent who runs the publisher’s book repair room.

He hands her a 180-year-old book he has just fixed, “a thin volume. Othello: The Moor of Venice”. He digs the previous binding from the bin and shows it to her.

“Not the original. That would have been calf or sheepskin. But this lasted about eighty years – not a bad innings; it was well read.”

Peggy says the new binding will last “a hundred, at least”. Eb nods. “Don’t mind the thought.”

Stephen Romei is a cultural critic

The Bookbinder of Jericho

By Pip Williams

Affirm Press, Fiction

448pp, $32.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout