The Australian’s Best Books of 2023

Fine literary fiction, fun memoirs and muscular Australian histories have made The Australian’s list of the Best Books of 2023, as judged by our stable of critics | WATCH

Geordie Williamson

The Pole and Other Stories (Text) is a perfect vessel for J.M. Coetzee’s late style – prose that is all economy and precision. The title novella, in particular, takes the author’s perennial concerns and distils them to pure essence. The result is one of the Nobel prize-winner’s most poised, distinctive works.

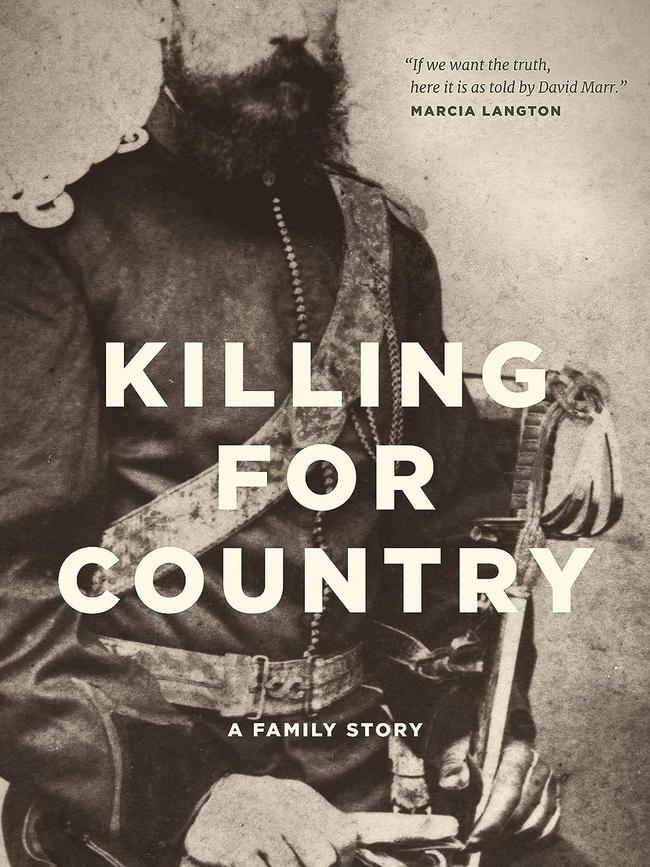

In a year marked by a tragic setback in relations between Australia’s First Nations and those who came after, David Marr’s Killing For Country (Black Inc.) – an account of two Marr forbears and their part in massacres of Indigenous Australians on Queensland’s Colonial frontier – speaks to our present as much as our past. Marr gives voice in these pages to those who had none.

“Snobs mind us off religion,” wrote Les Murray, wounded into anger by the death of his father. I think he would admire the unashamed attention granted by author Amanda Lohrey to matters spiritual in recent works.

Her new novel, The Conversion (Text), describes the efforts undertaken by a grieving widow to remake her life after moving into a country church in rural New South Wales. It is the work of a first-rate mind using fiction to find sacred order in an era of secular disarray.

Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting (Hamish Hamilton) is the finest novel so far by the finest Irish novelist of his generation. Domestic in scale but immense in implication, Murray takes one family’s post-2008 crash experience, melancholy and mundane, and turns into a universal account of the obligations we owe, both to ourselves and those closest to us. Finally, a work by a friend and former colleague. Matthew Lamb’s Strange Paths (Knopf) is the first volume of an immense biography devoted to Frank Moorhouse’s life and work. The fruit of years of research, Strange Paths doesn’t just capture the career of a hugely significant Australian writer – it’s a magisterial cultural history of post-war Australia.

Best of 2023

Stuck for last-minute gift ideas? Here are the best books of 2023

Fine literary fiction, fun memoirs and muscular Australian histories have made The Australian’s list of the Best Books of 2023, as judged by our stable of critics | WATCH

Our critic’s top 10 films of 2023

Do Barbie and Oppenheimer make my list of the best films of 2023? They sure do. They are great films that made lots of money. Win-win as far as I’m concerned. Here are the rest you won’t want to miss | WATCH

Your favourite recipes last year

These are the dishes you, or you fellow subscribers, have been cooking in 2023. How many have you made?

Stephen Romei

I’m always mildly anxious when asked for my books of the year because I know there are the shallows of what I have read and the bottomless ocean of what I haven’t. What if Moby Dick surfaced for air and I failed to spot him? Yet one isn’t paid for anxiety, so my book of 2023 is J.M. Coetzee’s The Pole and Other Stories (Text). The titular novella-length story, about an unromantic Polish classical pianist and a woman from Barcelona, is one of the most unconventional and remarkable love stories I have read. As is Christos Tsiolkas’s The In-Between (Allen & Unwin), centred on two mid-50s men who fall into hot love with each other but find it hard to leave cold loves behind.

Richard Flanagan’s Question 7 (Penguin), which opens with him being personally grateful for the bombing of Hiroshima, is his most intellectually complex and emotionally vulnerable book to date. It may also be his best.

Each of these books made me rethink and reconsider aspects of my life, as did Trent Dalton’s Lola in the Mirror (HarperCollins), which includes a hold-the-phone passage about living The Alive, capitals needed, that I’ve adopted as something of a mantra.

In nonfiction, where that bottomless ocean is even vaster, my picks are Catherine Lumby’s Frank Moorhouse: A Life (Allen & Unwin), a rollicking portrait of a great Australian writer that doubles as a candid examination of the challenges all biographers face; Ben Schneiders’ Hard Labour: Wage Theft in the Age of Inequality (Scribe), a headline-making exploration of the ever widening gulf between the rich and everyone else; and Chris Wallace’s Political Lives (UNSW Press), an informative, entertaining study of the relationship between Australian prime ministers and their biographers. A must-read for the Bob Hawke chapter alone.

Shankari Chandran

I read a lot of dystopian literature this year because there’s nothing like fictional global failures to make you feel better about the factual ones. Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts (Penguin Australia) hit the spot with its recognisable Trumpian autocracy and surveillance state, in which art is a form of political protest and the artist is finally a hero.

Eleanor Limprecht’s The Coast (Allen & Unwin) is a mesmerising exploration of love, isolation and bigotries in a forgotten place that still resonates today.

Set in a leprosy hospital in 1920s Sydney, Limprecht’s characters and prose are unforgettable and had me reaching for her back catalogue. Australian historical fiction at its finest.

R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface (HarperCollins) is much more than a story of manuscript theft, writer anxiety and the ensuing car crash of consequences. It delivers a laugh-out-loud critique of cultural mis/appropriation, the publishing industry and the author-agent-publisher love/hate triangle.

Christine Shamista’s debut poetry collection, Soft Side of Red (Gazebo), is a masterclass in the power of well-chosen words. Her poetry is raw, urgent and cutting. She deftly tackles themes of race, identity, family and matriarchy with innovative yet accessible form. Painful at times, and always beautiful.

Shehan Karunatilaka’s 2022 Booker Prize winner The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (Allen & Unwin) is a terrifically funny, chaotic and sometimes even silly ghost-story-meets-murder-mystery. Then it casually slips the profound horrors of Sri Lanka’s injustices onto the page. It is an incredibly effective literary strategy and gift from Karunatilaka.

Peter Craven

Richard Ford’s Be Mine (Bloomsbury) is a deeply moving and at the same time bizarrely funny story about a seventy-something father doing his best to look after a middle aged, always eccentric son with a motor neurone disease. The comedy is hectic and unstable as they head for Mt Rushmore but the compassion and complexity and depth of feeling are extraordinary.

J.M. Coetzee’s The Pole (Text) is written with the characteristic austerity of his late work but it hurls the reader into a world of suppressed feeling and revisions of feeling that are heartbreaking in their strangeness and the intensity with which an apparently cool and recollected world can flame into life. It’s a book about last things and the power of the heart that discovers its own unadmitted desires too late.

The South African-born Adelaide-based Nobel prize winner has a ghostly compositional grandeur that would be mannered if it did not have the grace and gravity of poetry and the capacity to bring alive the unimaginable.

Nicholas Shakespeare has written a masterpiece in his Ian Fleming: The Complete Man (Penguin) which is a multilayered life of the creator of James Bond, full of the possibilities of master spying and suffused with the warmth of the portrait of a protagonist of great talent and kindness and frailty. Nicholas Shakespeare’s book is better than almost any nonfiction ever gets, a work of literature in its own right.

Judi Dench, almost blind but with a photographic memory and a clairvoyant sense of the enchantment and abiding truth of the Bard glows with Shakespeare: The Man Who Pays the Rent (Michael Joseph).

Sam Neill’s Did I Ever Tell You This? (Text) is a charming, beautifully understated bit of remembrancing by a man who thinks he may be dying which is doubly alluring in its audio version with the crispness and modulation of the New Zealand actor’s self-mocking.

Richard King

I’ve been mostly reading nonfiction this year. James Bridle’s Ways of Being (Penguin) is a thoroughly original book, which explores non-human forms of intelligence – from plant-life to animals to artificial intelligence – with a view to resetting our relationship with the world and rethinking the terms on which we move forward into an increasingly uncertain future.

No less intriguing (and no easier to classify) is Naomi Klein’s brilliant Doppelganger (Penguin), which marbles the popular confusion between its author and another Naomi – Naomi Wolf – into a meditation on the online world of shouty podcasts and conspiracy thinking, and on such prospects for radical political change as can survive this information environment.

In philosophy, I’ve been enjoying (and quibbling with) John Gray’s The New Leviathans (Penguin), which argues that the era of liberalism is approaching its historical terminus, and relishing Raimond Gaita’s Justice and Hope (MUP), a collection of essays suffused with that thinker’s deep, and deeply affecting, humanity.

On politics, Guy Rundle’s Red, White and Blown (Hardie Grant) is essential reading for anyone wishing to contextualise next year’s Presidential election. Combining sharp analysis and gonzo-style reportage, it suggests that the United States is not only home to countless cults but also a kind of cult itself, and is reaching the point of total crisis.

Finally, David Marr’s Killing for Country (Black Inc.) is a prodigious work of scholarship on an issue that continues to divide Australia – the violent dispossession of its First Nations people. Beginning from Marr’s discovery that his ancestors worked for the Native Police, it is a difficult read but an essential one.

Gretchen Shirm

The book that resonated strongly with me this year was Charlotte Wood’s Stoneyard Devotional (Allen & Unwin) about a woman who withdraws from city life to live among nuns. Wood makes so much out of her sparse material: a mouse plague, the repatriated bones of a missing nun; I will never forget the almost gothic scene during the plague in which the mice animate a piano in the middle of the night.

Irish writer Claire Kilroy’s Soldier Sailor (Faber) blasts through the silences and injustices that attend motherhood, while also managing to capture the transformative power of the love one feels for a newborn. This book blazes from start to finish, particularly startling is the husband’s learned helplessness, and unwillingness to meaningfully meet the baby’s needs.

Also fierce is Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Chain Gang All Stars (Penguin), a speculative reality in which American prisoners are forced into gladiatorial-style fights to the death, all captured live on television. Bleeding into these wild imaginings are the cruel realities of the criminal justice system – it somehow manages to be both incredibly entertaining, while also leaving us with a creeping sense of complicity.

The other real discovery this year was Gwendoline Riley, whose forensic, unsettling examination of intimate and family relationships in First Love (Allen & Unwin) and My Phantoms (Allen & Unwin) are captivating. Love is deliciously complicated for Riley, who refuses to reduce relationships to pleasant experiences, and captures awkwardness, cruelty and frailty in the cleanest and crispest of prose.

Diane Stubbings

Two books about writers were mesmerising. Clare Carlisle’s The Marriage Question: George Eliot’s Double Life (Penguin Australia) stutely examines Eliot’s life and work through the lens of marriage. It made me want to start working my way through Eliot’s oeuvre all over again.

Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life (Hachette) by Brigitta Olubas is consummately written and researched. Providing crucial insights into the work of one of the nation’s pre-eminent novelists, this will rank among the great Australian literary biographies.

In novels, The Wolves of Eternity, (Penguin Australia) Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic yet intimate story of ideas, beliefs and existence kept me spellbound. Benjamin Myer’s Cuddy (Bloomsbury) lyrical hymn to the life of St Cuthbert and the efforts of Cuthbert’s followers to prevent his corpse from being desecrated by Vikings, is an unlikely page-turner. Finally, The Bee Sting (Penguin Australia) by Paul Murray is a gripping and humorous tale of a family at war with itself. While it bears traces of both Jonathan Franzen and Roddy Doyle, The Bee Sting is very much its own inspired piece of writing.

Helen Elliot

Best? This year I am narrowing it down to fiction. Then narrowing it again, to the most exhilarating Australian fiction, with one Swedish book for variety.

Paddy O’Reilly, Other Houses (Affirm Press): Janks and Lily are getting their lives together as they raise Lily’s daughter Jewelee in inner city Melbourne. Janks is an ex-junkie, sweet-natured and hardworking. Lily is practical, honest, clever, and cleans houses for a living. O’Reilly has a unique grasp on empathy, similar to Douglas Stuart of Booker winning fame. Here is Australian society laid out in the class schemes we dislike to own. Lily cleans the houses of those with enough money to pay her. But how do you get money? And how do you live? And then Janks vanishes and she needs to find him. Emotionally rich, gripping, original. O’Reilly is never less than first rate on every page.

George Haddad, Losing Face (UQP): set in Sydney’s western suburbs and told in the alternating voices of Joey, and his grandmother, Elaine. Elaine is a doting Lebanese grandmother with a difficult, secret past. Her daughter, Joey’s mother, is the first in the family to be born in Australia and has raised her two sons as a single mother, relying on her extended family, mainly women. Haddad has remarkably conjured the most endearing young man in Joey. Confused, without mentors or male role models his self-identity is vague. But he has a wide and intelligent empathy, thanks to the women in his life, and a real understanding of what is right and wrong. This tale of his involvement in a rape crime and the consequences is a cliff hanger without being cheap. The writing is urgent and exceptional.

Jessica Au, Cold Enough For Snow (Giramondo). A woman and her daughter, both unnamed, take a trip together in Japan. They haven’t seen one another for a long time because they live in different countries and both women are reticent to the point of being inarticulate. But being reticent doesn’t mean love, care, understanding, curiosity are absent. Or perceptiveness. In this succinct (98 pages) novel, Au calibrates what it is to have attachments, culturally, emotionally, and familial. Is it the perfect novel? Reading is like being invited into a ceremony to honour the connectedness of everything wonderful in the world.

Stoneyard Devotional, Charlotte Wood (Allen and Unwin): A late middle-aged woman arrives at a tiny, fading religious community somewhere in dry NSW countryside. She’s left behind a rich and active life in Sydney, a partner she loves and who loves her to search for what might be a different phase in a well-lived life. The thing is, she is not religious. She doesn’t believe in the cosy, absurd tales that surround her in the religious community. Then there is a mouse plague. Hideous. Monstrous. What do plagues tell us about ourselves and our specks of lives? An engrossing, tightly-written novel from the first line to the last. This rare imagination and daring is surely what we need right now in art of any kind.

Ia Genberg, The Details (Hachette). The narrator of this prize-winning Swedish novel is in bed with a fever when she starts to think about a book she was given a lifetime ago by her lover. It was, she thought then, the perfect love, everlasting. But it wasn’t. There are two more intense love affairs detailed in this uncanny book and there is also a tender excavation of the narrator’s bond with her loving but deeply damaged mother. The Details refers to the important details in the narrator’s life. The details are the people who have meant everything to her over the course of her life so far. They are the people who, when you rub against them leave traces in your skin, or perhaps your soul. The novel is a mere 155 pages, all chiselled. There is something worth remembering on every page. That’s how good this is. Written this way, life seems it will be interesting until we draw our last breath.

Joy Lawn

Praiseworthy (Giramondo) by Waanyi author Alexis Wright is the Australian Ulysses. A searing satirical yet lyrical allegory about Aboriginal Sovereignty, at more than 700 pages it requires commitment but is a transformative almost hallucinatory reading experience.

Equally masterful is Matt Ottley’s monumental The Tree of Ecstasy and Unbearable Sadness (One Tentacle Publishing), an awarded multimodal work of art, word, music and film. Like a phantastic Alice, it spirals through mental illness, metamorphosis and restoration.

Another surreal illustrated book for older readers is Paradise Sands: A Story of Enchantment (Walker Studio) by Levi Pinfold. To save her brothers, a sister must withstand three days of fasting while others feast. Original, allusively layered and technically brilliant.

The Concrete Garden (Walker Books), by national treasure Bob Graham, is a picture book for all ages. Playing together, children transform ordinary, grey life through rainbow colours. They inspire the world. Suffused with humour, this book celebrates community, diversity, joy, hope and wonder. Flawless.

Wonder and innocence are threatened when a five-year-old’s childhood friend is snatched in Lucy Treloar’s slow-burning literary thriller Days of Innocence and Wonder (Picador). Damaged survivor, Till, changes her name and tries to outrun her fear. Sculpted, charring storytelling.

Bright Shining: How Grace Changes Everything, by Julia Baird (4th Estate), is the book for our jaded, wounded age. The author’s quest for “awe, wonder and light” leads her to seek grace, discovered through undeserved kindness and love, forgiveness and beauty – a liberating gift that is “bright shining as the sun”.

Lucy Sussex

In no particular order: The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka (Sort of Books). The Booker is a curate’s egg, but occasionally it is spectacular. The 2022 winner was wild, imaginative, and full of bitter truths. Writing recent civil war is inherently dangerous, without the gaudy supernatural. Yet the book succeeds exuberantly. It could have crashed completely in the last third, but changed tone effortlessly with redemption, and leaving earthly vanities behind.

White Holes by Carlo Rivelli (AllenLane): When life on Earth seems unbearable, consider the cosmos. Rovelli’s science-writing is STEMA (+ Arts). For his tour of black hole theory the guidebook is Dante’s Inferno. What might the inverse, a white hole be? A genuinely cosmic read.

Conquest by Nina Allen (Quercus): Some of the best fiction is interstitial, defying classification except as good. Here Allen sends a PI searching for a lost conspiracy theorist. It gets increasingly uncanny, with classical music, old pulp SF, alien spores and crime gangs. The realist meets the outlandish, expressing our uneasy Zeitgeist.

Pet by Catherine Chidgey (Europa): Child abuse takes many forms, the near-undetectable being among the worst. Chidgey’s superb psychothriller is set in suburban New Zealand, where childhoods are meant to be ideal. Justine has a crush on charismatic teacher Mrs Price; and so has her father. The sweet turns sinister, the narrative momentum ensuring the reader cannot look away.

Restless Dolly Maunder byKate Grenville (Text): The novelised memoir is a balancing act between art and truth. Grenville’s subject is the grandmother she hardly knew, a difficult woman. Dolly was denied education, doomed to dull domesticity. Humans finding evolutionary niches, she exploited her skills in small business. The book is an absolute triumph of lost Australian vernacular – and also a personal expiation.

Paul Monk

Of the books I have reviewed for The Australian this year, the standouts would surely be Sung Yoon Lee’s The Sister: The Extraordinary Story of Kim Yo Jong, the Most Powerful Woman in North Korea (Pan Macmillan) and Serhii Plokhy’s The Russo-Ukrainian War (Penguin). The first a rare glimpse behind the walls of the awful regime of the Kim dynasty. The second, the most authoritative account of the roots and early course of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Three other books stand out as brilliant reads: Robin Lane Fox’s luminous and path breaking Homer and His Iliad (Penguin), Daniel C. Dennett’s delightful and impressive memoir of a life in the philosophy of mind I’ve Been Thinking (W.W. Norton & Co.) and Benn Steil’s The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White and the Making of a New World Order (Princeton University Press), which I’ve owned since it was published, but only read in October, as part of my preparation for giving a paper in New York in early November on the stresses in the current world.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke

My favourites are these: Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) by Adam Steiner (Backbeat Books) whose gorgeous prose and yearning for aesthetic delirium never fails to hit the mark. A blur of fact, interview and memoir, it transports readers into a universe of near-agonising responsiveness, and is worth reading for that alone.

Enchanted Forests: The Poetic Reconstruction of a World Before Time by Boria Sax (Reaktion): while a cigar can sometimes simply be a cigar, a tree, as American academic Boria Sax understands, is never simply a tree. As he explains, “Forests become a blur of brown and green that people think of as outside of time.” In this beautiful volume, Sax explores the mythology, poetry, and spiritual resonance of trees with a reverence characterised by love.

The Art of Darkness: The History of Goth by John Robb (Manchester University Press): Membranes bassist, British punk entrepreneur, alt model, and cultural critic John Robb, freshly returned from a knockout book tour of America, almost single-handedly resurrected Goth. A runaway international bestseller, its central concept was – outrageously – plagiarised by a number of other writers, but Robb’s remains sovereign.

Before We Say Goodbye (Before the Coffee Gets Cold Book 4) by Toshikazu Kawaguchi: This simultaneously profound and whimsical series explores the relationship between love and time within the context of yearning. Kawaguchi’s lightness is characteristically Japanese – the prose reads almost too easily, leaving the reader wishing the experience could be prolonged. This is, of course, in keeping with the series’ theme, which is why sales run in the millions.

The Myth of the Wrong Body by Miquel Missé (Polity Press): Spanish academic and trans activist Miquel Missé’s monograph on the need to expand the First World’s narrow gender norms – conduct, dress, sexual expression – rather than resort to sometimes disastrous genital mutilation is not merely compelling, but an important read. What if, he asks, we simply relaxed our cultural understanding of gender to embrace differences?

Samuel Bernard

When it comes to combining in-depth historical research with gorgeous and heartfelt storytelling, few others are in the same league as Pip Williams. The Bookbinder of Jericho (Affirm) is my historical fiction book of the year and I know I join a long queue when I say, I cannot wait for the next book by Pip.

Whenever Eleanor Catton releases a new book, you stand up and take notice. The Booker Prize winning author has created a truly gripping psychological thriller in a style that is genuinely unique to this wonderful author. It is for this reason, that Birnam Wood (Allen & Unwin) is one of my top picks of 2023.

Who doesn’t adore Sam Neill? I fell in love with this man in my teen years watching The Dish and Jurassic Park. So, when I first heard he was writing a memoir, Did I Ever Tell You This? (Text), I was ecstatic, and his delivery is every bit as good as I had hoped. My signed copy sits in a prized position on my shelf.

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright (Giramondo) could be the most important book of the year. Winner of the 2023 Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, it is a magical realism masterclass that takes on some vitally important social issues. Wright is a brilliant writer with a voice that cuts through to audiences at home and abroad.

Richard Flanagan is a national treasure and one of the finest novelists we have ever produced. Question 7 (Penguin Random House) skilfully explores the impact of choices and the chain reaction that our decisions can set off. This hybrid blend of genre could be his finest work.

Emma Harcourt

I’ll start with The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon (Simon & Schuster). This is the first historical I’ve read from her, and it is brilliant. Based on the life of renowned 18th century midwife, Martha Ballard, who must investigate a shocking murder, you’ll feel deeply unsettled by the prejudices and secrets running rife through the town of Hallowell, Maine, in 1789.

Women & Children (UQP) by Tony Birch. This book is a beauty to read and will stay with you for days. The writing is elegant and understated, and Birch perfectly captures the naivety of our protagonist, 11 year-old Joe, and the loss of that childhood innocence when his aunty turns up beaten and in need of help.

The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell (Hachette): Renaissance Italy, a famous painting, a young woman married off to satisfy her father’s needs, and a husband intent on murder – you’ll not be able to put this one down.

Lady Tan’s Circle of Women by Lisa See (Simon & Schuster) takes you deep inside the lives of women healers in 15th century China, with fascinating historical detail and a moving story of female friendship.

One Illuminated Thread by Sally Colin-James (HarperCollins) is a debut that delivers in spades, with a sweeping story of three women in different centuries, Colin-James writes from the heart.

The Escapades of Tribulation Johnson by Karen Brooks (HarperCollins), who brings her talent for writing charm and cheek to the voice of Tribulation Johnson in this tale of female playwrights in Restoration London. An immersive and entertaining read.

The Seven Skins of Esther Wilding by Holly Ringland (HarperCollins) who gently weaves folklore and symbolism into the story of a family’s trauma as our heroine, Esther, follows the trail left by her absent sister from Tasmania to Copenhagen and the Faroe Islands. This is richly rewarding and very readable.

Lola in the Mirror by Trent Dalton (HarperCollins): I must include this gem of a book, and Dalton’s best so far. There are oodles of warmth and charm in Lola and her story, as well as an honest, startling picture of homelessness and domestic violence in Brisbane.

OUR CRITICS

Geordie Williamson has been chief literary critic of The Australian since 2008.

Richard King is an author and critic. His most recent book is Here Be Monsters: Is Technology Reducing Our Humanity? (Monash University Publishing, 2023)

Gretchen Shirm’s most recent novel The Crying Room was published this year.

Diane Stubbings is a writer and critic, based in Melbourne.

Peter Craven is a culture critic.

Helen Elliott is a writer and critic.

Joy Lawn is a critic specialising in literary fiction, YA and children’s books.

Lucy Sussex is a writer and critic.

Paul Monk is an analyst of world affairs and a poet.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke is the author of Apple: Sex, Drugs, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine.

Samuel Bernard is a literary agent, writer and critic.

Stephen Romei is an editor, writer and critic.

Emma Harcourt is an author and critic. Her most recent book is The Brightest Star.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout