The Archibald Prize: stranger than fiction?

Each year, the crème of our most respected artisans hurl themselves into the pit against any boob who can hold a brush, only to howl in distress when the inevitable happens.

Sydney artist Jason Benjamin (RIP) once spoke for the nation’s art mafia when he described the Archibald Prize as like a fight outside a pub. “You know you shouldn’t encourage it,” he said, “but you can’t help but stick your head out to take a peek.” Each year, the crème of our most respected artisans begrudgingly hurl themselves into the pit against any boob who can hold a brush, only to howl in distress when the inevitable happens and the most popular – or least popular – wins. Maybe next year.

Seems local literature has caught the bug, too, with the publication of at least two novels whose action gambols around the national portrait prize.

The first is Naked Ambition by Robert Gott, a man who’s prolific if nothing else. He’s written more books than are on most private shelves, the best ones of the crime genre. Political satire with art as the centrepiece is not quite Gott’s schtick, and we are given a fright on page nine when junior minister Gregory Buchanon shows his commissioned nude portrait to his wife.

She said, “It’s much larger than I expected. The scale I mean. Obviously.”

Those of us raised on Benny Hill and Dick Emery may have cause to fear the next 229 pages of double entendres and phallic wowsers. Mercifully, it gets better. As Gott gets into his folly he begins to have mature fun with it, and the reader can’t help but roll with him.

The plot is actually good. Gregory Buchanon, a decent but arguably stupid politician, decides to get a nude portrait painted for the Archibald Prize, presumably to cut some cred with the voters; courage, transparency and all that. His wife is ambivalent, slightly concerned. His mother-in-law is outraged, thanks to her puritanical Christian axe to grind, and threatens to derail Buchanon at the forthcoming election if he doesn’t destroy the “abomination”. The artist, proud of her work, is not happy when she hears the portrait may not show, so she takes drastic action. All sorts of hell breaks loose.

One of the joys of Gott is that he has a fine bullshit detector when it comes to politico speak. Listen to this, a little monologue delivered by Buchanon to his family, in the family home, where the media can’t see.

“Be that as it may, the fact of the matter is, and let me be perfectly clear on this, the subject exists without the artist, the artist doesn’t exist without the subject.”

What a wally, and a well-observed one at that. The fact Gregory is spouting this press conference sludge to his own family is testament to how soaked he has become in the art of using many words to say nothing at all. He’d go far, if it wasn’t for that blasted penis.

But Gott doesn’t eviscerate Buchanon. The author has affection for his buffoon, to be sure. Gott knows that innocently egotistical men are drawn to politics, the theatre of which takes place on grand stages in austere buildings, the whole production threatened by mere moments in private places, flatteringly lit mirrors and behind late-night laneway dumpsters. So much for political theory.

Naked Ambition is an old-school farce, an accelerating car-crash whose survivors are probably the least deserving. We can name check all the way back to Ben Jonson’s Volpone (1606) to find the joists in Gott’s scaffold, but it’s less dreary to declare what we have here is a modern play in a traditional framework. Three distinct acts take place mostly in one room of the Buchanon house, which is really Gott’s way of telling us that these homes in which we dwell are where politics begins and ends. The fact there are so many knocks on the door, always startling to those inside, may be more than just theatrical necessity, but a constant reminder of the perilous and transitory world of the Australian politician today.

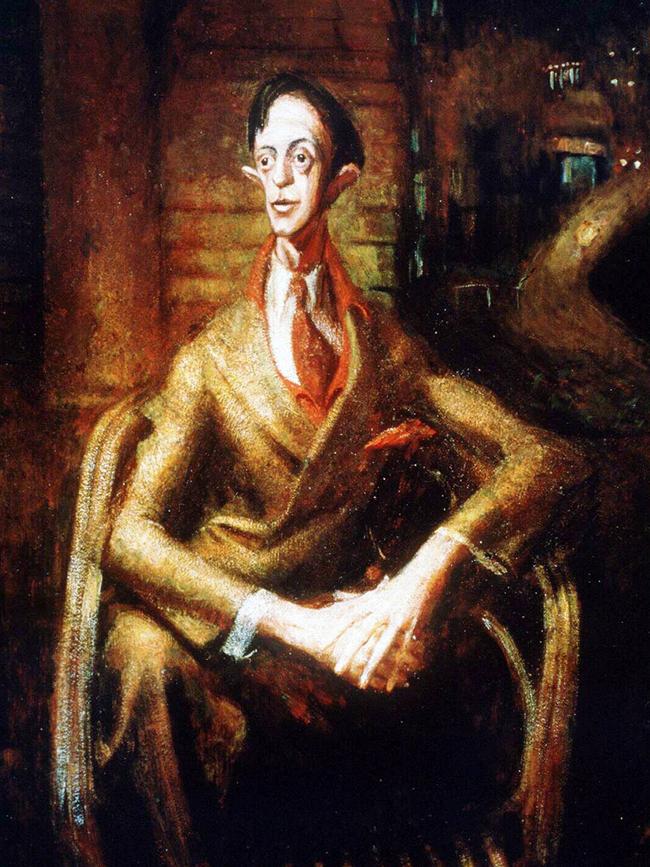

Artists, too, live in a world where one reckless move can derail a career, and this is the central tension of Kim E. Anderson’s The Prize, a book whose cover tells us is: “Inspired by the real-life events of the 1943 Archibald controversy.” Students of art know the story well enough. When William Dobell won the Archibald Prize with a striking portrait of his friend and fellow artist, Joshua Smith, the resulting public controversy, driven by two sore losers who stirred a conservative wartime media, found its way to the Supreme Court of NSW, the last place on Earth where art should be adjudicated. Dobell was ultimately vindicated, Justice Roper calling Dobell’s entry a true portrait and not a mere caricature, as had been charged by the prosecution.

But the damage was done. Dobell abandoned Sydney art society for the tranquil shores of Lake Macquarie, his brush cautiously angled so as to never paint such a controversial stroke again. Joshua Smith won the Archibald the following year in a moment of token appreciation and he knew it, disappearing into a self-imposed obscurity and, like Dobell, rarely spoke of the “offending” portrait. Nor did the former friends ever speak to each other, the end of the affair cruelly underscored when the painting itself was ruined by fire in 1958. Dobell refused to restore it, the blackened canvas reimagined by English art conjurers until it returned to Australia, ironically enough, a caricature of its former self.

In The Prize, Kim E. Anderson makes the bold decision to imagine for us the passion and intrigue that took place behind the closed doors of “a poignant love story with shattering consequences” for two famously private men. Those outraged by such a premise would do well to remember that conservative outrage is the very enemy here. Dobell himself once said: “You might say I am trying to create something instead of copying something, when I set out to paint a portrait. To me, a sincere artist is not one who makes a faithful attempt to put on a canvas what is in front of him, but one who tries to create something which is a living thing in itself, regardless of the subject.” Kim E. Anderson needs look no further for the artist’s blessing.

Christopher Bram took similar liberties in 1995’s Father of Frankenstein, later rendered faithfully on screen as Gods and Monsters, the 1998 film starring Ian McKellen and Brendan Fraser. The difference is, having made the decision to invent, Bram made bolder decisions still: Whale’s homosexuality was front and centre, even used as a ratchet to get young men to disrobe for dubious purposes; upon deciding to suicide, Whale tried to get his young gardener to unwittingly euthanise him. If used in true biography such devices would amount to heresy, but Bram made plain his story was fiction, and thus these episodes served his portrait well, that of an old man, his loves and lusts and regrets behind him, preferring oblivion if he can’t have it all again.

Anderson doesn’t back her own imagination to take such courageous decisions. It’s surely to her credit she did the research and tried to authentically render conversations based on recollections of the players involved, but the net result is a cut-and-paste intimacy, known views sent back in time and recontextualised into private settings. Take this exchange, supposedly taking place as Dobell asks Smith to sit for him.

“Don’t you ever give up?” said Joshua. “You forget how well I know you! You will overemphasise – in your own way – distort me … That won’t please me, nor will I let a painting determine who I am.”

Having seduced the reader into accepting The Prize as a dream based on fact, the author rewards us little besides that which is already presumed by the official record. And it’s not as if there are no mysteries here that could be exploited. Were Dobell and Smith romantically intimate after all (there is no evidence in The Prize that they were, or anywhere else for that matter)? Why did William paint Joshua as such a cadaverous wing nut anyway – was the very idea some kind of public revenge for a private wrong? Considering there were so many – including Smith’s family – who were desperate for the portrait to be destroyed, who lit the blaze that wrecked it in 1958?

In Robert Gott’s Naked Ambition, we have a novel crying out to be performed on stage. Similarly, Kim E. Anderson, an alumni of Nine Television and Southern Star Network embarking on her first novel, should know that The Prize is a tantalising synopsis for film, a gift for a confident director and two young actors of equal parts muscularity and vulnerability. All it needs is a little of Dobell’s daring – his desire to take the truth and stretch it – and we’ll have another Australian masterpiece. Any controversy can go to hell.

Naked Ambition by Robert Gott (Scribe, Fiction, 240pp, $22).

The Prize by Kim E. Anderson (Pantera Press, Fiction, 320pp, $27.99).