Sydney Opera House stands as monument to genius

Its gleaming sails may be the site of a new culture war, but as the Sydney Opera House turns 45, we take a look at a side rarely seen.

Dawn is looming as I make way down Sydney’s Macquarie Street towards the harbour. On my left is the building known as the Toaster; in the hotly contested field for Sydney’s Most Loathed Building, it’s a frontrunner. Before its construction, Sydney spruiker Alan Jones was a fervent critic. “It’s a monstrosity,” he thundered. The developers, of course, got their way and Jonesy then bought a $10 million flat, high up and with fabulous views in No 1 Monstrosity.

On the other side of that is Circular Quay, the birth ward of white settlement. It should be one of the city’s most loved spaces. It’s not. The Cahill Expressway divides the city from the harbour, like a Trumpian wall. Below that, on the waterfront, is where former NSW minister, now inmate, Eddie Obeid secretly and corruptly held the leases on a clutch of government-owned cafes. Eddie’s Eats were turgid but still hugely profitable because of the immense foot traffic. Converting public assets into private wealth is a Sydney specialty.

Then those sails come fully into view and all other thoughts are abandoned. A jogger sweeps past me, slows to a walk, then halts, hands on his hips in wonder. “It is one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity,” UNESCO says. “Not only in the 20th century but in the history of humankind.” It is truly breathtaking. No matter how many times you may jog past it or view it from the bridge, the wonder never ceases. Today, it’s 45 years since it opened and it’s forever stunningly modern.

Possibly the most wondrous aspect was that it was built at all, on this spot, in this city. As author Helen Pitt recounts in her recently published book The House, the architect who finished the project, Peter Hall, reckoned Sydney had a far greater chance of getting something “resembling a Leagues Club than a piece of monumental sculpture on Bennelong Point”.

Today I am being afforded a rare privilege, the chance to crawl around the innards of this monumental sculpture and up on to the top of those famous sails. My guide for the day is Dean Jakubowski, a former carpenter who is now the house’s building operations manager. He’s like a jockey handed the reins of Winx; he still can’t quite believe he got this ride. It’s his 10th year in the saddle.

The men who built the Opera House walked around it in gumboots and Dunlop Volleys and with durries hanging from their bottom lips. I had to complete an hour-long physiotherapy assessment a couple of days before I’m strapped into a safety harness, and with appropriate footwear, for the journey.

As we wander around the building, Jakubowski tells me he is constantly amazed by its beauty, the quality of the workmanship and the attention to detail. Recently he employed a team of tradesmen to abseil the entire building, tapping the 1,556,006 tiles, looking for ones that were loose. They found 12.

He takes us into the concert hall to get our bearings. “We are about to head up to the sails,” he says. “Essentially we are going to walk along the main catwalk that goes across the ceiling of the concert hall, which will take us to the crown area, which is the circular area you see there, which is above the Grand Organ, and then we are going to make it all the way across to the top.” We walk up a series of stairs and into the shell of the building.

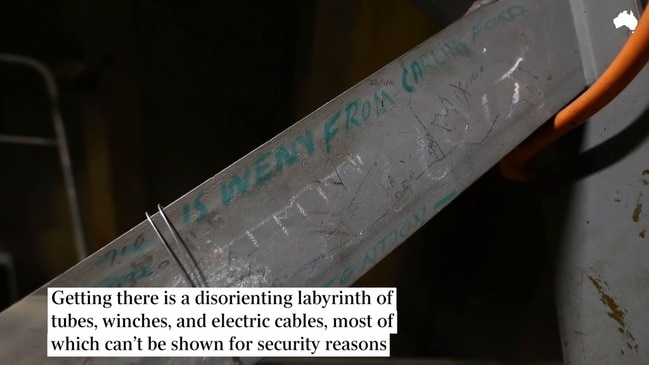

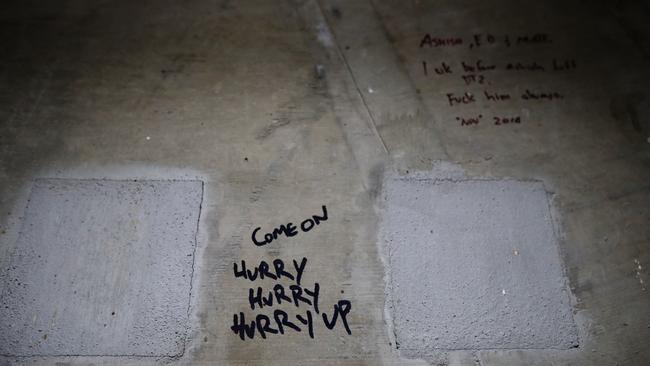

It’s a labyrinth of tunnels and tubes, winches and electric cables. You can see up close how the shells were constructed with giant concrete Lego pieces, held in place by wire cables. The intricate engineered geometry is beautiful. And here, hidden from public view on the innards of this architectural wonder, are the bogan slogans of those who toiled here. We learn that “Pommies are big arseholes”, that Porky was “Fired from Wormalds — 2007”, that Wendy from Strathfield allegedly possesses amazing sexual talents.

Dozens of new Australians worked on the tools and the multicultural contribution has not been forgotten: “Napoli is always wanking his prick.” “Bob 17/7/71” has left us with a permanent chalk rendition of his junk on chipboard, Bob’s Knob. There are some fine abstract renditions of the female form.

We head higher up the concrete tunnels, squeezing through holes, and over bolts, and up ladders through this modern-day pyramid — it’s like something from Indiana Jones. Finally we come to a hatch. Jakubowski opens it and the morning sun comes streaming in and a big smile breaks out across his face — he’s been up on the roof for maintenance checks a couple of times a week for the past decade and still he’s excited. I haul myself up through that hatch and it’s like a rush of amyl.

I hook on to the safety line and come out looking directly down the spine of the shell towards the Domain and Government House. To the right are the skyscrapers of the city above Circular Quay. As I turn clockwise I face the Observatory and The Rocks, and then the full splendour of the bridge. I look up the spine of the northwest shell. The gap between the two sails is called “the cleavage” and I perve through the feminine forms across the water to the houses of power, Admiralty and Kirribilli.

Past the northeastern shell you look up over Fort Denison, with the sun sparkling on the harbour, to Sydney Heads. The view then sweeps around from the tip of Mrs Macquarie’s Chair to the Royal Botanic Gardens. Sydney may have done its best to obscure views of the Opera House, but the house couldn’t give a toss. This is the Everest of vistas. The city will grow and change and evolve but the Opera House and its harbour will remain; it will outlast all it surveys.

■ ■ ■

Those men, and a few women, who built the house are all so very old now. Joern Utzon, was just 38 when he dreamed up the concept — he’d have turned 100 this year. It was a glorious and tumultuous period for those who toiled on it, and, a bit like men who fought in wars, it would send some mad. Others sought peace in the drink. Many would forever carry their scars, but life would never be quite as exhilarating again. They’d never feel as fully alive as when they worked on the house. Few will be around to see its 50th birthday in five years.

High up in the grandeur of the Joan Sutherland Theatre, John Rourke, 79, a retired Sydney architect, eases himself into a seat; his bum sits snugly like a foot in an old boot. As a young architect Rourke worked with Hall on the difficult task of picking up the pieces when Utzon resigned in 1966. “I got asked to do something which, on reflection, was close to impossible,” Hall said of this poisoned chalice. “And I’m certainly not sure that if I were offered it again now, I would take it on.” Rourke says the pressure his friend endured, coming in after Utzon, did him in. “It killed Peter Hall, all that lauding of Utzon,” he says.

Part of Rourke’s brief was seating. “We’d whittled it down to five different prototypes of these seats,” Rourke recalls, lounging back and looking down on the stage. He’d been dispatched to Europe for a couple of weeks “on a fact-finding tour with a chap from the public service … to see how continental seating worked”. They shuffled in and out of Europe’s grand opera halls, putting their bums on seats.

On his return numerous prototypes were built. The favoured designs were then tested for acoustics in a 1-10 scale model of the theatre; the seats had to absorb sound, occupied or empty. Many thousands of hours of thought and sweat had gone into designing the prototypes, and on this day it came down to just five and they had to make a choice. Rourke’s colleagues argued, around and around, about which one to choose. Finally he said to them: “I am going to resolve this.” He sat for a time in each of the five chairs and chose one. “The one that was most comfortable for my bottom was the one that was selected.” His was a date with destiny. Rourke says Utzon was undoubtedly a genius. “All the other competition entries were basically boxes,” he says. “This is a building that you can look down on and you often do. It needed to be an exciting sculptural shape.” But Utzon’s building had serious design faults that were left to others to correct. “Because the sails couldn’t be built with a thin shell, like he envisaged, he ended up losing a huge amount of volume and that created all sorts of problems with the acoustics and so forth, and with the accommodation required under the rules.”

A group to which Rourke belongs, opusSOH, is lobbying to have Hall and the team that completed the interiors recognised on the Opera House site.

Rourke is immensely proud of the work he did and says he never worked again on a building that came close to being so wonderful and ambitious. “It is very solid, very well crafted. I think it will remain forever. If you look at the grand medieval cathedrals, they were built in 1200 and they are still here today.”

He remembers when the first trial concert was held on site and everyone who worked there was invited to an 11am show. Rourke was seated next to a labourer. “All these guys in dinner suits walked on to the stage carrying instruments and he wanted to know who they were.” Rourke informed his labouring colleague that it was the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. “He said. ‘Gee, they look smart don’t they? What do they do?’ I said they play the musical instruments. ‘What, for a job? Jesus, I can tell you that’s better than pushing a barrow of wet concrete.’ ”

Legendary unionist Jack Mundey was one of those who pushed barrows of wet concrete around the Opera House. He was a labourer on the site from 1959 to 1960, before he went on to become an official with the Builders Labourers Federation, initiating the famous green bans that saved much of old Sydney from demolition. He’s 89 and hard of hearing but still passionate about the rights of workers. I meet him with his formidable wife, Judy, in a cafe in Surry Hills.

“I realised the importance of it at the time,” he says. “The very position of the Opera House … you could see as the building was going up it was going to be very impressive. I knew it would always be special but I wanted it to be recorded that the workers played a part, a very important part.” He too played a very important part. The government of the day forgot to plan for carparking. It wanted to raze the grand old figs in the Domain and pave it for cars. The BLF, led by Mundey, put a green ban on that idea. The Domain was saved, an underground carpark eventually was built.

Engineer John Burgmann, 76, was on his university holiday — between third and fourth year — when he did his first stint on the building. “I was there at a really interesting stage, the erection of the roof was going full steam ahead,” Burgmann says. He was up there as the giant concrete blocks were lifted into place. “There was a lot of very precise surveying required to make sure that these precast elements, which made up the roof, dangling there in space, joined together in the right place.”

He had a couple more stints and later worked on the design of the glass walls. All of it was satisfying work, he says. “We go there irregularly for concerts and plays, but whenever I pass it on a ferry, or looking across when it is being used for Vivid, I feel very satisfied, very pleased. I am very glad to have worked on it.”

So, too, is Vince Ashton, 80, who spent two stints there, once as a scaffolder to allow the tilers access to tile the roof and later as a rigger. “We were aware it was an unusual design and also aware that the engineering was very difficult,” Ashton says. “There were times when the company used to provoke us to go on strike so that they could save money. They’d turn on a blue with us over one of our requests and then we’d walk off for a day or two. That saved them money. Bastards.

“I go down there a bit,” he says. “I went at Christmas time with me two daughters and we saw circus acts and that inside the play theatre on the side. When I walk in there a lot of memories come back … it is a grand old building and it is entitled to its world heritage listing. It really is. I feel very proud that I was able to work on it.”

After I had arranged to speak to Louise Herron, the chief executive of the Opera House, all hell broke loose when she refused to allow advertising for a horse race to be broadcast on to the famous sails. You may recall, her neighbour, Jones, blasted her on radio and threatened to have her sacked. She seems remarkably unfazed by the bruising encounter when I meet her a few days later.

Herron says it was just another week in the history of the house. She tells me about a day she had last year. Herron went to an incredible concert by great American violinist Joshua Bell, “an absolute genius”. He was playing a 300-year-old Stradivarius, possibly the most perfect musical instrument ever made. He was performing work by Tchaikovsky, “a human creative genius”, inside the concert hall of the Opera House, a work of architectural and engineering genius. The next day she showed US Vice-President Mike Pence around the building. Last week she was busy preparing for the visit of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle.

The dogs may bark but the Sydney Opera House rolls on.