Soldiers away and at play, in love and war

Loneliness is always a factor in infidelity, but for the soldier abroad it is compounded with fear and the apprehension of imminent death.

War and love have a long and complicated history. Ares – Mars to the Romans – was never a popular god, and all his sons were psychopaths like the Thracian king Diomedes who fed guests to his flesh-eating mares until he was killed by Heracles. Ares is regularly called grim or hated because he brings about the death of men in battle, and yet his name is cognate with the Greek words for male and for virtue; similarly, the Latin “virtus” etymologically means manliness.

According to Hesiod, Ares was married to Aphrodite, and the union of the male principle of discord and strife with the female principle of concord and desire was expressed in the name of their daughter, Harmonia. Numerous paintings in the Renaissance evoke this relationship, including well-known works by Andrea Mantegna, Sandro Botticelli and Piero di Cosimo, and the idea of a harmonious balance of the male and female was so appealing that many couples had wedding portraits painted in the characters of Mars and Venus.

In this state of equilibrium, the potentially destructive power of Ares is neutralised by the complementary force of Aphrodite and his energy can be tamed and put to good use.

Although he doesn’t make the connection explicitly, Hesiod also memorably writes of the difference between good and bad strife: bad strife leads to war and death, but good strife is the drive of ambition and emulation that makes each man seek to excel all others at his craft – and he cites as examples the potter, the carpenter, the poet and even the beggar.

But the balance is disturbed by war: the Trojan war begins with the illicit love of Paris and Helen, whose ultimate cause was the Judgement of Paris, which itself came about because the goddess Strife was not invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, the parents of Achilles. During the war, the Greek leaders take captives as concubines; on the long journey home Odysseus becomes the lover of both Circe and Calypso, while longing for his wife Penelope who is waiting at home, beset by suitors.

Agamemnon’s fate is particularly grim; in his absence his wife Clytemnestra takes his cousin Aegisthus as her lover and on his return from 10 years at war they murder him. Her crime will be avenged many years later when both she and Aegisthus are killed by her son Orestes, returning from exile. Agamemnon’s brother Menelaus is more fortunate: he is reconciled with his adulterous wife Helen and they seem to find happiness together again.

Thus, war releases bad strife, but also unregulated desire which can itself become the source of strife and harm. Men and women are separated; soldiers are exposed to danger, hardship and the threat of imminent death; women are left with drudgery and sometimes economic difficulties at home; both are lonely. Irregular relationships spring up on either side; infidelity and guilt take their toll; relationships sometimes weather these disturbances, sometimes break down or end in violence, and sometimes reknit and rebuild.

Homer tells of the perennial experiences of men and women in wartime, and the epic narrative is echoed by the stories collected in this small but well-chosen exhibition at the Shrine of Remembrance. Some decades ago, such a show would probably not have been possible, at least in an official memorial museum, because the topic of sexual infidelity – both of soldiers on campaign and of spouses at home – has long been a sensitive one, as we see in the exhibition itself. It is to the credit of the curators that they avoid both the tacit censorship of the past and the moralistic editorialising so pervasive today.

Loneliness is always a factor in infidelity, but for the wife or girlfriend left behind, it is aggravated by the boredom and demands of everyday life, while for the soldier abroad it is compounded with fear, hardship and the apprehension of imminent death. For many a young soldier, a night or two in some foreign brothel may be his first and last experience of pleasure – and perhaps even erotic affection – before meeting a premature end on the battlefield.

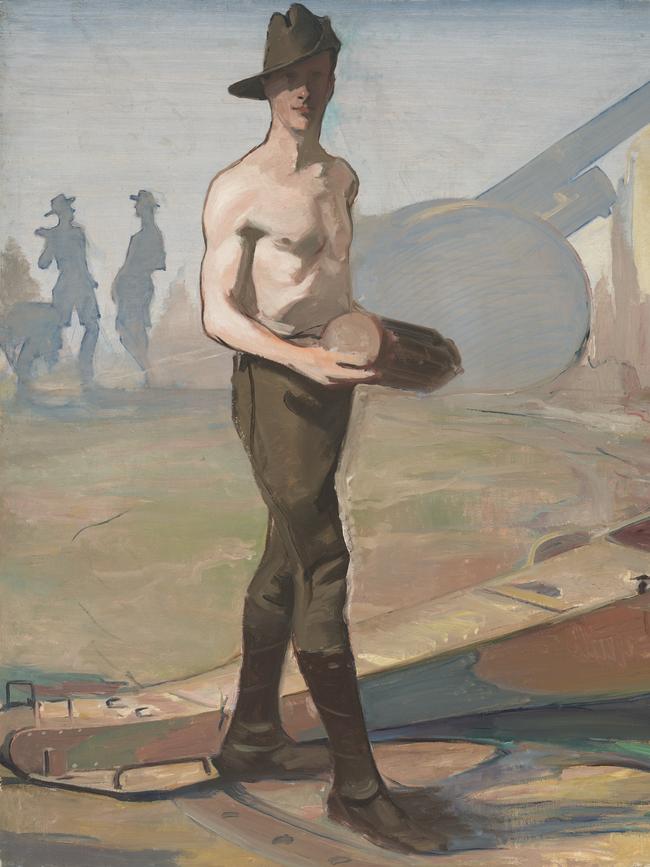

More interesting, though, are the women with whom soldiers have less obviously mercantile relations. It is a cliche that women are attracted to men in uniform, but there is a reason for such attraction: the uniform of a soldier marks the man who wears it as one who faces danger. Strength and courage are inherently attractive qualities, and the shadow of death adds pathos and a thrill of urgency to the relationship.

Dalliance abroad is evoked in several works. Colin Colahan’s Scottish Idyll (1942) shows a young Australian soldier talking to a Scottish girl by the River Nith at Dumfries, with the 17th-century Devorgilla Bridge on the left. The relationship, as the title suggests and as the composition confirms, is quiet and close rather than quick and desperate, while the background effectively matches the young woman with the handsome white house across the river, and the soldier with the tall and martial form of the castle.

A very different kind of relationship is implied by Will Dyson’s lithograph Compensation (1918). Here, a tall and lithe young man slouches on the left in an attitude half-diffident, half-sullen, gazing at the statuesque and rather imperious young woman on the right. The implication, as the catalogue points out, is that “a business transaction is about to take place”; she has presumably named her price for half an hour of pleasure on a summer afternoon and he is trying to make up his mind.

The converse of such situations was the dalliance of Australian women with Allied soldiers, particularly Americans, stationed in Australia. Sidney Simon’s watercolour Soldier and Woman (1943) shows a relatively demure conversation between a GI and an Australian girl, under the watchful eye of a Military Police officer. But Australians, including servicemen, were alarmed by the presence of the Americans, who were reputed to have a lot more money to spend on impressionable girls.

Albert Tucker was particularly horrified by the apparent decline of wartime Melbourne into a pit of vice, from the predatory inmates of brothels keeping watch from their balconies, to the teenage girls who became groupies for American soldiers: “All these schoolgirls from 14 to 16 would rush home after school and put on short skirts made out of flags – red, white and blue – and go tarting along St Kilda Road with the GIs and, of course, diggers”.

Roy Hodgkinson’s One Sunday Afternoon in Townsville (1942) offers a more documentary account of flirtation and promiscuity, and includes the black American servicemen who were a subject of particular anxiety because of their sexual reputation.

All of these concerns, as already mentioned, were exploited in enemy propaganda, illustrated here by a Japanese leaflet titled “Hey! You diggers! He came, he saw, he conquered” (c1942). On the right, Australian soldiers and sailors lie dead or dying, but one has his eyes open and seems to see, as he expires, the vision of his girlfriend with a GI that occupies the left-hand side of the composition. The text begins (with curious American-style spelling): “Thinking you ‘diggers’ will never come back alive, tha BLACKS and tha YANKS are raping your wives, your daughters, your sweethearts – they’re helpless without your protection.”

Sexuality has important implications for military discipline and security at many levels, from the management of venereal disease – evoked in several items in the exhibition – to the use of female spies to seduce male officers and extract information in the course of pillow talk or social banter, again evoked in a wartime poster.

This is especially true because soldiers tend to be young men in the most sexually active phase of their lives, and yet they are separated from women and forced to live in an all-male environment. Military forces today have more women than in the first half of the last century, but women are still far less likely to be involved in front-line and combat roles.

Armies have also had an ambivalent attitude towards homosexuality, which has generally been officially prohibited until very recently, even though military life has always been characterised by both homosexual relationships and male friendships which can sometimes come very close to overstepping the line of mateship.

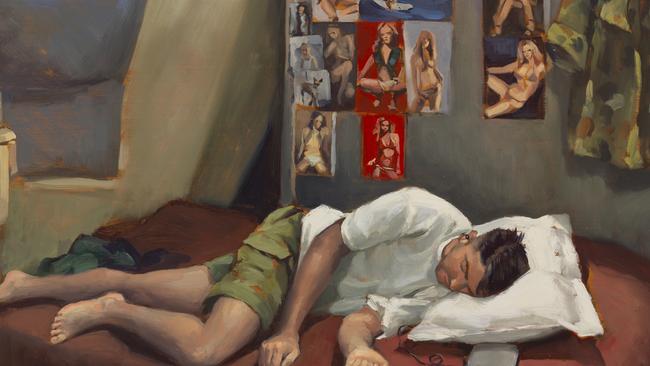

This kind of anxiety manifests itself in the display of girlie pictures and centrefolds in Peter Churcher’s painting of a young soldier sleeping in his tent on the island of Diego Garcia (2002), not so much a source of erotic titillation as a reminder of what he really desires.

It finds an outlet, too, in drag acts like the one commemorated in Geoffrey Mainwaring’s Female Impersonator (1945), or another described in the catalogue and on the accompanying wall panel, where according to a witness, a young female impersonator in 1943 was “so convincing that the soldiers singled out for his attention and caresses blush furiously and lower their eyes, just as though a real woman were teasing them…”

It is not only the years of separation in wartime that are difficult, but also the reunions that follow. Relations with wives or girlfriends may be rebuilt, like that of Menelaus and Helen, even if each understands, either expressly or tacitly, that one or both has been unfaithful. Or they may founder on that knowledge, or on something worse, such as a soldier bringing home a venereal infection – again evoked in a poster in the exhibition.

Soldiers can return traumatised and unable to readjust to domestic life. The dead can haunt those left behind in various ways. It must be hard for a man, especially a civilian, to marry a girl whose fiancée was killed in battle. While the husband works through a lacklustre career at a desk in an office and grows old, fat and bald, the dead hero remains always, in the wife’s mind, as handsome, brave and noble as when she last saw him.

In spite of all this, war also brings people together and forges relationships that would not otherwise have come about. As we learn from the exhibition, more than 12,000 Australian servicemen brought home foreign brides from World War I, and about 10,000 Australian women went back to America with GIs in WWII.

Most memorable, perhaps, are several touching personal stories, including that of Slim, a young Australian who escaped from a POW camp in Salonica. He was sheltered by an English-speaking schoolmaster and, several years after his benefactor’s murder by the Nazis, ended up marrying his daughter Xanthoula.

Lust Love Loss

Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne, until

November 1

Lust Love Loss

Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne, until

November 1

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout