Snapshots of a regional success story: Ballarat event ramps up

A photographic event like few other: Ballarat Foto Bienniale is leading the way for the presentation of art in Australia

A biennial event such as this, inherently composed of a great many separate exhibitions of very different scale, ambition, quality and character, is far more enjoyable scattered through a regional Ballarat than set out in a succession of spaces in a sterile urban contemporary art gallery.

Even within the core program, it offers the visitor an interval of refreshment and reflection between experiences, and naturally makes it easier to embrace a variety of less established and more idiosyncratic work in the open program.

As we saw with the Sydney Biennale’s use of Cockatoo Island over several years, certain kinds of art benefit from being shown in complex and evocative environments rather than in neutral and bland white boxes. Sometimes, and at best, this is because a contemporary installation will genuinely engage with the ambience and vestigial history of an abandoned site; at other times the intrinsic interest of the site supplements or compensates for that of the work displayed.

In any case, a city such as Ballarat has just the right scale for this dispersed exhibition format, because it has so many handsome and significant public buildings within a relatively small area, and especially if the weather is fine, visiting the exhibition also becomes a pretext for discovering the city and its history. It’s a wonderful thing, too, for the city to attract so many visitors and to be reminded that historical buildings whose upkeep must sometimes feel like a liability are also among its greatest cultural assets.

It was fascinating, for example, to enter the Mechanics’ Institute (1860) for the first time and to discover its library reading room and historical book collection. The name is perhaps not widely familiar today, but the Mechanics’ Institute movement, which began two centuries ago in Edinburgh (1821) and then Liverpool (1823), Glasgow (1823), London (1823) and elsewhere, played a vital role in adult and technical education at a time when university access was very limited and only the most academic subjects were taught.

Australia was not slow to follow the metropolitan example: The first Mechanics’ Institute here was opened in Hobart in 1827, followed by the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts (1833) and the Newcastle School of Arts (1835). This became a common name in Australia and schools of arts are often among the most impressive buildings in regional towns, even when many of their citizens have little idea of the range of library and technical teaching functions they once provided.

Among the many other interesting buildings that are being used to exhibit parts of the Biennale are the Town Hall (1870-72), the Mining Exchange (1887-89) and the Regent Theatre (1920s).

Upstairs at the Town Hall, for example, is a collection of portraits, in one of which I was shocked to recognise an old friend, Robert Nelson, recovering from a serious bicycle accident.

Sitting in a wheelchair, he is photographed against a backdrop that he painted himself, naively evoking a classical landscape with a framing tree on one side and a Roman arch on the other.

The confusion of figure and ground in a whimsical setting makes the impression of suffering all the more poignant.

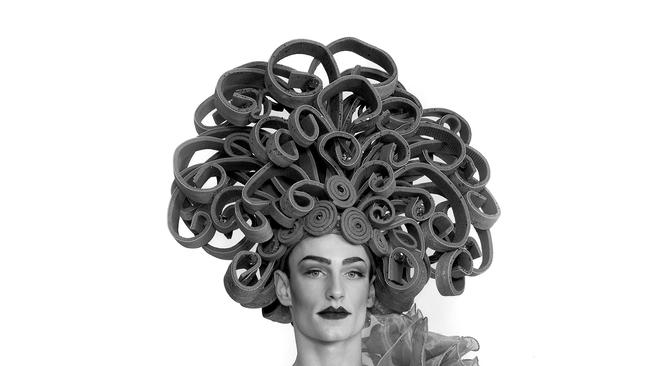

The Real Thing, curated by Jeff Moorfoot, who was the founder of the Ballarat International Foto Biennale, is a collection of regional Victorian photographers, whose subjects are often drawn from their local experience even though there is nothing provincial about their skill or talent. The viewer is first struck by a series of black and white, life-size portrait photos which illustrate this point: They are extremely accomplished, clear and gripping, but evoke the complexities of regional life where, for example, a drag performer can be found side-by-side with a father teaching his son to hunt with a bow and arrow.

Other series in this exhibition are devoted to landscape, notably a sequence that represents various Indigenous massacre sites, accompanied by statements by descendants of the victims; another that evokes a sense of time through images of trains, tracks and bridges crossing the countryside; a third that ponders the gradual end of the age of coal power; and finally a fourth series which started with images of the cold but poetic landscapes of Iceland and has continued in New Zealand and the Faroe Islands.

Particularly interesting are a couple of individuals who have chosen to turn away from the facility of digital photography in pursuit of authenticity – or “the real thing” of the exhibition title. One has reverted to one of the earliest forms of photography, ambrotype, in which each image is a unique object, to explore a strange dreamworld that recalls both surrealist experiments and 19th century spirit photography; the other uses large-plate negatives printed, as in the 19th century, by direct contact, to produce a set of landscape images whose low-key vividness and sense of authenticity caught my eye as soon as I glimpsed them.

One of the most ambitious international artists in this year’s event is the Swede Erik Johansson, whose work occupies the whole of the vast space of the Mining Exchange (the Biennale’s administration is in the Exchange’s old offices upstairs). As the festival booklet informs us, Johansson uses “no computer generated, illustrated or stock photos … just seamless combinations of his own photographs. It is a long process, and he only creates eight new images per year.”

At first sight, Johansson evokes a world poised between charm, whimsy and the more seriously disconcerting. There is the gently ironic The Swedish Space Program, in which a pretty blonde would-be astronaut stands in knee-deep grass while a picturesque little traditional Swedish house is angled as though about to be fired off like a rocket. Other images with an astronomical theme include one of a group of workers about to hang a moon in the sky and another of a stargazer looking up into the blank heavens while the meadow at his feet is spangled with fallen stars.

The influence of Magritte, both in spirit and in certain techniques, can be felt in many of these works. It’s particularly striking in one of the more subtle but visually intriguing works, in which what at the top of the picture looks like the gabled end of a house emerging from a blank wall, turns in the lower part of the picture into a gateway in the wall leading into a sunlit field with a blue sky and clouds above. The most elusive thing about this work – hard to achieve in painting but harder still in photography – is the way it conceals the point at which one reading turns into the other, at which a positive form turns into a negative one. The fact that these complex images, though digitally assembled and manipulated, are all based on actual photographs of the world, sets them apart from the new category of computer or AI-generated images which are already beginning to pervade the world of commercial art. This year, for the first time, the Biennale includes an AI-generated category, with the title Prompted Peculiar, but these works were not yet on display when I visited Ballarat and will be discussed in a week or two.

The core exhibitions in the Biennale naturally tend to be in the vicinity of Ballarat Art Gallery, but I recommend starting with a wide-ranging walk, dropping into various peripheral exhibitions, both because it is pleasant to visit the city while still fresh, and because the most important work should stand up to inspection even if you have been walking around for a couple of hours. In fact, the art gallery has one particularly important exhibition, which is so striking that it would make an impact no matter how tired you were.

There are a couple of others, notably a series of works reminding us it is now the first anniversary of the murder in Iran of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, who had been detained by the morality police for failing to wear the compulsory hijab in the approved way, which provoked an unprecedented wave of demonstrations against the Islamic Republic. A series of photogravure landscapes is also interesting, as is a collection of Andy Warhol’s polaroids, especially if you missed the much bigger exhibition devoted to Warhol and photography at the Art Gallery of South Australia and reviewed in this column in March. The most impressive work in the whole festival is, not surprisingly, the main one devoted to the Greco-British photographer Platon. The exhibition begins with a documentary film the artist has made about his own work and career and which effectively helps bring to life the many photographic portraits of the great and the famous – as well as the poor and the oppressed – that make up the exhibition itself.

We see him, for example, preparing for a portrait sitting with General Colin Powell. The setting is minimalist, with white and black backgrounds so the figure and especially the face remain the whole focus. His subjects perch on a plain wooden crate with a cushion, and when he tells Powell – with perfect timing, just as he is sitting down – that Vladimir Putin and Colonel Gaddafi have sat for him on the same little box, the general half-leaps up in surprise.

And this is all part of Platon’s method. He is a consummate technician, working with colour but above all with black and white photography, using an analog camera, real film stock and enlargement on to photographic paper, albeit with a detour via a high-resolution scanner to correct the negative and heighten the tonal contrasts that he loves.

The analog camera, as is pointed out in the film, importantly means he is not looking at a screen, but directly through the SLR at the subject. He has a vivid sense of composition, sometimes used with heightened foreshortening for sensationalist effect, but at its best when more restrained, as in the touching portrait of a young Congolese mother holding her child in her arms.

But just as the celebrated portrait painters of the past were not just masters of the brush but also famous for being able to form a connection with kings, popes and other great and distinguished sitters, inducing them to reveal something of their inner lives. Platon, too, for all his technical virtuosity, concentrates almost entirely on trying to generate the vital electricity of connection.

That’s why he starts with the trick of mentioning Putin and Gaddafi.

Immediately he breaks through the barriers of nervousness, formality and self-consciousness that we bring into unfamiliar settings as defences against our own vulnerability. Surprise and humour jolt the sitter into presence and establish a rapport.

Platon is not a big man, but he brings a uniquely intense yet perfectly calibrated energy to bear on his subjects which compels them to let down their guard and momentarily open themselves to his camera.

Ballarat International Foto Biennale, Ballarat Art Gallery and other venues, until October 22

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout