Sixty years ago, a bold newspaper was launched and - amid establishment fear and loathing - television came to Australia

Sixty years ago, a national newspaper was launched and – amid establishment fear and loathing – TV came to Australia.

The year the new paper boldly called The Australian arrived, TV was still only eight years old. And in 1964 the so-called “magic lantern” continued to be viewed with some suspicion in establishment circles, even as “TV dinners” became alarmingly popular.

They were heated and served in disposable trays, thus eliminating food preparation and dishwashing. Bonds even advertised “Look-Alike” TV pyjamas for mothers and daughters with loose-fitting candy-striped jackets and plain pants. We, the public, loved TV, even as highbrow critics still predicted the end of conversation in the family home, its inhabitants comatose under an evil spell.

In government, the conservative ivory towers of academe and the powerful churches there remained deep scepticism as to its worth. They hated that it would bring people into the queen’s drawing room and there was even a suggestion by one critic that TV would stalk her family so intimately that lip-readers could tell what they were saying to their ball partners.

Many believed that nothing short of a nuclear Armageddon would deliver the world from this electronic Antichrist.

A quagmire of debates had held up its introduction. Timing was a major issue; those who wanted a rapid introduction pointed to the fact that former “enemy nations” had TV before we did. A telegram was sent to prime minister Robert Menzies urging his government to ensure we didn’t lag behind such countries as Siam and Japan, and “even Omsk in Siberia has television’’.

But we loved it when we got it. And it became part of our lives with alarming speed, heaping thousands of images upon a sleepy national consciousness. With the veneered box in the lounge room, the suburban home remained the dominant icon of the most desired way of life, to the chagrin of many architects.

Even by 1964 there was much public concern over what should be allowed to be broadcast, what was appropriate, and what was “generally acceptable in mixed company”.

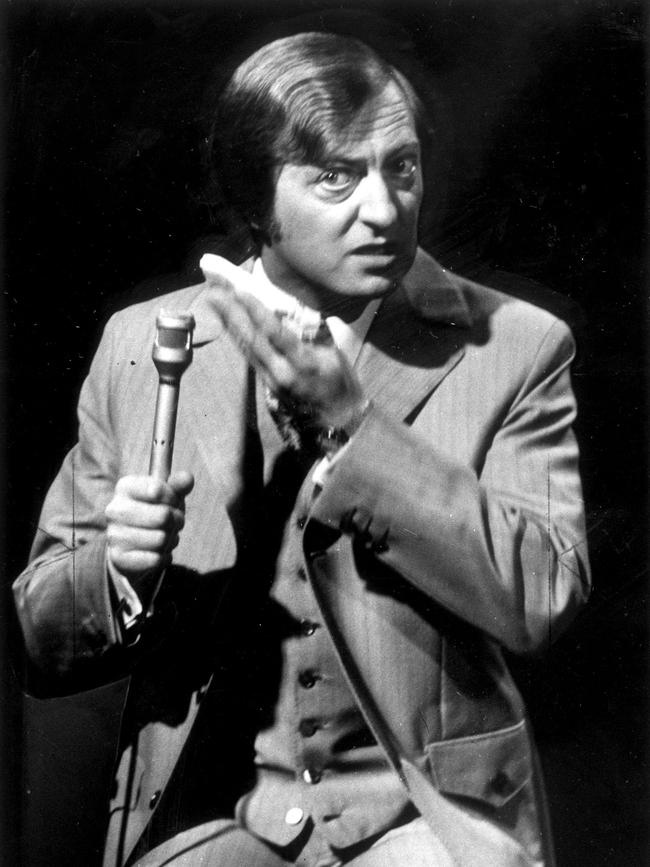

Graham Kennedy was still the King of TV, at least in his home city where In Melbourne Tonight was about to rack up 2000 performances. (A composite show called The Best Of Kennedy was sent interstate and soon he was seen all over Australia when the coaxial cable started operating between our major cities.)

He was unstoppable, boasting of the “cartloads of cash’’ he was earning as he pricked the pomposity of governments, station management and whatever took the rapid Kennedy eye.

He caused a quarter-million cathode tubes to blush pink when he used the Great Australian Adjective on camera midway through the year.

This was the first time anyone could remember the expletive being used on a local variety show and it caused as much shock in Melbourne homes as the English Profumo scandal involving government ministers, spies and prostitutes had done. More people per capita watched Kennedy than any other television show in the world.

It was also one of the few places on TV where the Australian voice was heard. Most presenters had English accents and there was little local production.

“Our actors were vocal chameleons who could do Noel Coward, Shakespeare or the toffee voices required for the English drawing room comedies imported by JC Williamson,” Phillip Adams, one of this paper’s earliest TV critics, said. “They could make a fist of Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams. But the first thing an Australian actor learnt to do was to get rid of his or her embarrassing Australian accent.”

Then, in October 1964, Hector Crawford’s Homicide arrived and didn’t leave our screens for 512 episodes. The show introduced Jack Fegan as Inspector Connelly, Terry McDermott as Detective Frank Bronson and Lex Mitchell as Detective Rex Fraser. As the series evolved they were joined by Leonard Teale and Charles “Bud” Tingwell.

I was there too in the opening episode, The Stunt, an actor from Melbourne University already working in ABC radio drama. I had auditioned successfully for the formidable Dorothy Crawford, who managed casting for the company.

She also produced serials, plays and crime series, such as D24 and Consider Your Verdict, the second of which was later adapted for television in 1961, running into 1964. I was an extra in the episode in which a group of students staged a mock bank holdup to publicise a charity. The leader, played by young singer Ian Turpie, was shot dead by a bank guard.

I would appear in many more Crawford shows over the years. I built a career as a petty crim with a bad Tony Curtis haircut having the fear of God hammered into me by Leonard Teale. “Let me go, me brother made me do it,” I told them. Or, “The tow truck driver started it”.

Hector Crawford implicitly understood how the populist construct of the modern-day police drama demonstrates an intrinsic robustness that supports complex issues. He was fond of saying “cop shows will never leave the screen because by the nature of their jobs cops are in life-threatening situations”.

He was right, too. But he had to work hard to create a local TV industry, given the disdain for anything Australian shared by the network bosses. However, he was a great salesman. He was usually accompanied to network meetings by his friend, veteran actor Alwyn Kurts, who often looked slightly malignant, hooded and dangerous.

“I can’t remember ever opening my mouth but I learned a lot about selling,” Kurts told me years ago. “Hector would never let them close the door. Just as he thought they were about to say ‘No’, he’d jump to his feet and say, ‘All right, we’ll think about it and get back to you in a month’.”

Hector and his mute sidekick eventually sold the engagingly down-at-heel, nitty-gritty, black-and-white cop show and Homicide became part of our social history. (Hector had had to mortgage his house to pay for the pilot, and Seven initially paid far less than the production cost.)

All of Australia went on to watch Homicide over the subsequent decades. There might have been shaky scenery, a muffled line, dropped cues. the odd boom shadow, and endless sequences of cops getting out of cars and going into buildings, but we watched it for other things.

While individual episodes might not have been memorable, when you spent so many hours in the construction of its cosmology, the experience was a rich one. Simple identification and suspense yielded to the subtle nuances of cohabitation – rather like a long-running marriage.

Homicide became a ritual pleasure offering reassurance in its familiarity and regularity; audiences became accustomed to hearing Australian accents and to seeing dramas worked out in their own streets.

So 1964 witnessed not only the birth of a newspaper but paved the way for a growing demand for Australian-made television drama and an opportunity for Australian actors to work in their own accents.

It also saw the debut of Carol Raye’s often bawdy The Mavis Bramston Show. Its resounding success surprised many, even the people involved in its creation, most of whom didn’t believe they would be employed past the pilot.

When she first suggested the idea of a revue-style, topical satirical program based on the UK’s hugely successful and news-oriented That Was The Week That Was, to James Oswin, general manager of ATN 7, he told her: “I’m not sure if Australians are ready to laugh at themselves.”

But with her customary flair and style Raye persuaded him to finance the pilot, quickly finding Gordon Chater and Barry Creyton as Australia’s answer to Bernard Levin and David Frost, and was herself, a little reluctantly, persuaded to take on Millicent Martin’s role.

They all came from successful irreverent revue stages in Melbourne and Sydney, and, consummate performers, they lampooned almost every aspect of Australian life, ridiculing the rich, the famous and the powerful. Mavis herself seldom appeared, a symbol of every English import ever brought to Australia, historically an elephant’s graveyard for washed-out Brit performers.

As critic Sandra Hall suggested, the show’s production of weekly comic commentary “was like publishing a newspaper, except for the spirit of high camp in which it was done”.

While 1964 was a big year, who could have predicted that as we celebrate 60 years of this newspaper, the TV we once all gathered around as a kind of electronic hearth would begin to disappear as new technology and marketing strategies push it into exciting new possibilities?