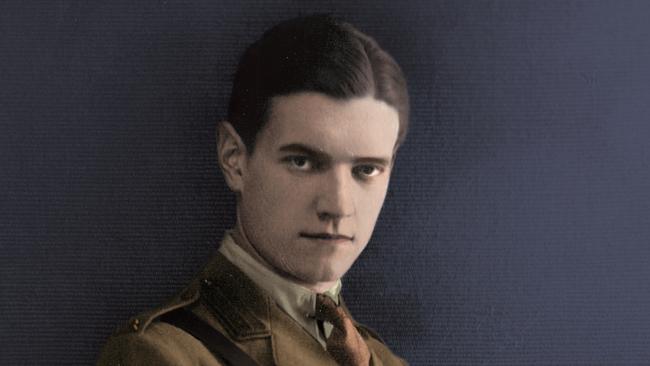

Sex, gossip and parties in the diaries of Henry ‘Chips’ Channon

The early diaries of American playboy Chips Channon were blasted as ‘vile, spiteful & silly’. A new, unsanitised edition is even better.

It’s all very F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Young man from Chicago escapes to Europe with some of his father’s money (shipping and banking), volunteers for the American Red Cross in France, sits between Proust and Cocteau at dinner in Paris, is briefly a Yank at Oxford, cultivates rich, powerful and (mostly) aristocratic friends, writes two bad novels, becomes a British subject and seems never to work for a living until elected to the House of Commons, where he lusts for a peerage but has to settle for a knighthood.

But he writes diaries, and that is why we remember him. The title page of this first volume is slightly misleading because there are two significant gaps in the period 1918 to 1938: there are no diaries for the years 1919-22; 1930-33, and gaps of some months in several years.

Chips: The Diaries of Sir Henry Channon (1967), edited by Robert Rhodes James contained a mere 250,000 words from more than two million. As Simon Heffer explains in his Introduction, not only were the diaries bowdlerised to minimise scandal, and redacted to avoid offence to living persons, such as Elizabeth the Queen Mother, but Rhodes James never sighted the originals. He had to rely on what he was given by Channon’s trustee, and lover, Peter Coats. Despite its sanitisation, Nancy Mitford called the volume “vile & spiteful & silly”, which helped sales.

Heffer’s edition is compelling. Channon is well served (no innuendo intended) by the almost flawless and detailed footnotes on every page, often as bitchy as Channon himself, but less reactionary.

Channon was part of a small but perfectly formed diaspora of Americans who relocated to Britain, including Henry James, John Singer Sargent, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Many women brought rich dowries with them and married upwards. Winston Churchill and Harold Macmillan had American mothers; Lord Curzon’s two wives were American, as were the Duke of Westminster’s unhappy wife Loelia, the famous hostess Emerald Cunard, and most importantly, Wallis Warfield, later Duchess of Windsor.

Channon was born in 1897 but he lied about his age so often, and so pointlessly, that he became uncertain himself.

In 1933, a year without a diary, he married Lady Honor Guinness, daughter of the Earl and Countess of Iveagh, and was a major beneficiary of the Guinness brewing empire. His in-laws provided lavish accommodation at Belgrave Square in town and Kelvedon in the country. He became an inactive Guinness director.

In Mayfair, the Duke and Duchess of Kent lived next door to the Channons. Kent, younger brother of Edward VIII and George VI, wild, bisexual and an addict, was married to the beautiful Princess Marina of Greece. Prince Paul, Regent of Yugoslavia, married to Marina’s sister, Olga, seemed to spend more time in Mayfair than Belgrade.

Channon became obsessed with Paul and thought him a great man. They may have been lovers. The neighbours became a virtual menage à six (or cinque, because Honor was often away with her ski instructor).

Channon was not a Nazi but greatly admired Hitler, Mussolini and Franco as bulwarks against Communism. He was flattered to have been entertained in Germany by Joseph Goebbels. Not a Catholic, he loved the ceremonials, dressing up and Papal absolutism. As the diaries make clear, he was an eager sexual experimenter.

In 1935 he had been elected as Conservative MP for Southend and held the seat until his death in 1958. Representing Southend was essentially a family business and between 1912 and 1997 the constituency was held only by his father-in-law, his mother-in-law, Channon himself, and his son Paul.

In Parliament he regarded Ramsay MacDonald with contempt, looked down on Stanley Baldwin, loathed Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden and Harold Macmillan, despised Clement Attlee.

He adored Neville Chamberlain, describing him as “the greatest human since Christ”, but detested his half-brother Austen Chamberlain, Nobel prize winner and former Foreign Secretary, because of his hostility to Hitler.

Channon’s excitement about Neville Chamberlain is puzzling. Chamberlain’s background was mercantile, a reformist Lord Mayor of Birmingham, and austere. He was not Oxbridge educated, a party goer or a gossip, did not marry into the aristocracy and refused all honours for himself and his wife. Sexually, he may have been a total abstainer. His interests were literature, nature and music. Immensely capable in domestic affairs, this led to a tragic overconfidence that he could “manage” Hitler and avoid a major war.

He worked briefly with Richard (“Rab”) Butler, then Under Secretary at the Foreign Office.

Chips Channon saw W.S “Shakes” Morrison as a man of destiny. (Morrison reached his pinnacle as Viscount Dunrossil, Governor General of Australia, dying in Canberra after exactly one year).

“Chips” had no difficulty in holding two contradictory opinions simultaneously. He loved, admired and was excited by Edward VIII both as Prince of Wales and king, but also despised his weakness and failure to lead, or sacrifice.

Channon’s snobbery is often toe-curling. “I am really annoyed that we are not invited to the court ball tonight … I am not impressed by the sovereigns: I know them too well and [Queen] Elizabeth, for all her charm and guile is no better than Honor [his wife] – an earl’s daughter.”

The diaries include four great set pieces: Lord Curzon’s funeral at Kedleston (1925), the abdication of Edward VIII (1936), the coronation of George VI (1937) and Chamberlain and Hitler at Munich (1938). Parallels with Samuel Pepys and Marcel Proust are more than plausible and I look forward to the next two volumes.

THE DIARIES: 1918-38