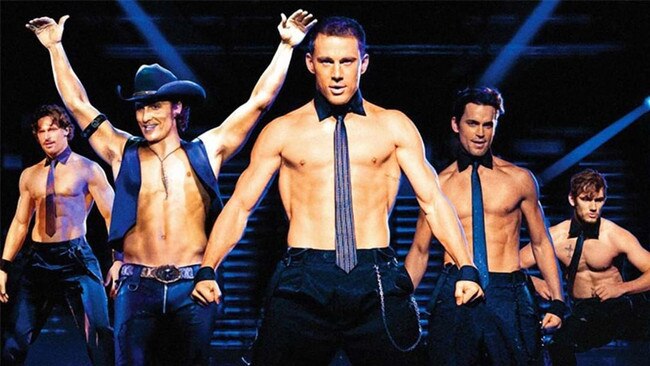

How Magic Mike went from sexy stripper story to global business success

Despite appearances, the live spin-off from Channing Tatum’s major motion picture franchise is all about women.

Magic Mike Live is a male strip show where men take off their pants the regular way – at the ankles, not ripped down a side-seam of snaps. The dancers give women roses, ask for slow dances, don’t speak unless spoken to and scram if they start weirding anybody out, leaving only the scent of coconut in their wake. The full monty is not skin, but a sensitive guy talking to the crowd about consent. “Permission,” he says. “Before you enter a lady’s space, you should always know that you’re welcome.”

The language of empowerment and self-care is employed liberally at Magic Mike Live, a dance revue based on the 2012 movie starring Channing Tatum. Tatum and Oscar-winning director Steven Soderbergh spent $7m to make that film, an almost-satirical look at the towel-snapping world of male strippers. Just over a decade later, Magic Mike is a $500m-plus brand that spawned two more movies, live shows with years-long engagements in Las Vegas and London, and a multicity North American tour that’s kicked off in Miami.

Magic Mike is making the surprising business calculation that male stripping, done in a certain way, can be marketed as wellness for women. The movie franchise is now aimed at women over age 35, a group more likely to sink $200 into an anti-ageing cream than $20 into a man’s G-string. Yet the brand’s success has given rise to an unusual kind of live entertainment that blends the unleashed libido of a bachelorette party with the safety of a book club.

“I’d let any one of these guys give my mum a lap dance,” Tatum says of the performers whose dance skills are more on display than their skin in a show that features pants and briefs instead of mesh tops and G-strings. He says he is as floored as anyone by the brand’s success. “If you told my 18-year-old self the crazy, circuitous route I was going to take to land here, I would have been like, ‘Man, your drugs are incredible.’”

The third film, which opened last week, Magic Mike’s Last Dance, is inspired by the live show, connecting the movie to the real version in the same feedback loop that has helped build the brand. The film will mostly live on streaming platforms after a limited theatrical release. The two-way promotional traffic between the new movie and the live show comes as the streaming boom meets a major postpandemic rebound in live entertainment. The film once again stars Tatum as Mike Lane, based on the actor’s stint as a teenage stripper in 1990s Florida. Mike is now a Miami bartender and retired stripper who falls for a new character, the older and richer Max, played by Salma Hayek Pinault. He gives her a private dance, she is forever changed and they head to London to create a new kind of strip show.

The Magic Mike brand began as the brainchild of men: Tatum, Soderbergh, writer-producer Reid Carolin, producer Peter Kiernan and others. It enters the tricky territory of female desire, taking it as a given that certain women feel exhausted by the work-life juggle and a youth-obsessed culture that writes them off. The live show, which was inspired by the sequel and which in turn inspired the new movie, includes female locker-room talk and men busting suggestive moves, but at its core it is an unusual kind of wellness experience. The founders flipped the script on the male striptease, making it less about a man’s self-regard and more about attention that women don’t always feel in real life. At the start, it was unclear if taking the movie into the real world would even work.

Not long after the first film, a friend of Carolin’s came back from a bachelorette trip to a Chippendales male strip club and said two weeknight shows were packed. “Oh wow, people are still doing that?” Carolin recalls thinking. He pitched the idea of a live show to Tatum, a close friend and creative partner he met on the set of the 2008 war drama Stop-Loss.

“I was like, ‘Absolutely not. That world is really kind of dark and weird,’” Tatum says. But he kept mulling it over, thinking if he created a live show without some of the scuzzier elements of male stripping, it might be worth a try. To test the premise, Magic Mike choreographer Alison Faulk sent out a questionnaire to her female friends asking what kind of strip show they would like to see.

“Every single person on that list, these incredibly strong creative women that we thought were going to have a trove of ideas on what we should create, actually none of them said anything,” Tatum says. “They were like, ‘That’s not a show that I would go to.’”

So the team set out to figure out what women would watch. In 2016, they set up a confessional booth in New York’s Times Square where strangers were invited to describe their desires anonymously. Tatum sat in it secretly behind a screen for 10 hours, talking to women who said everything from “I want a man who makes good money” to “I want a man who loves dogs.” That feedback also led to a female MC who calls the women in the audience queens and says they always deserve to feel empowered, loved and respected, “because you’re enough, girlfriend”.

The live shows ignore the “no touching” rules of strip clubs. The men put women’s hands on their bare chests or the back pockets of their pants. Patrons who don’t want to participate can say “unicorn”, the show’s safe word, and the performers move on.

Before they are hired, the cast of professional dancers – men who have performed with artists including Taylor Swift, Lil Nas X and Lady Gaga – are vetted with questions like, “Do you love your mother?” The aim is to weed out performers with an ick factor, since a show that’s off by two degrees might as well be off by 180, Soderbergh says.

The immersive performance is largely focused on the hip hop-infused dance skills of its stars, though the marketing also leans into the image of the show as a spray-tanned and baby-oiled fantasia. The production challenges the idea that women’s libidos are more driven by emotional connection than visuals, though its creators say the performances are not only about half-naked bodies but also about intimacy. Magic Mike Live is directed at straight women, though it is also popular with gay men. The founders say they’re looking into ways to broaden the brand so it recognises more than one gender identity.

Magic Mike movies are not Marvel bonanzas and they’re not indie darlings. They’re exactly the type of mid-budget project that has been struggling at the box office in recent years. The trick, says Soderbergh, is making the movies a happening: “You need material that can be event-ised.”

The Magic Mike universe stretches back more than a decade. Tatum was developing an idea about a stripper movie, which he mentioned to Soderbergh on the set of the director’s 2011 action thriller Haywire. Later, the two decided to collaborate on the project and financed Magic

Mike themselves, which gave them a greater share of the 2012 film’s $167m haul. Next came 2015 movie Magic Mike XXL, also based on Tatum’s past, about his trip to a stripper convention (the film left out Tatum’s transportation – a removal truck). That $14m film made $117m.

For years, no one could come up with a good idea for a third Magic Mike movie. Then, in 2019, Soderbergh saw the Magic Mike Live show at London’s Hippodrome Casino. “I really wasn’t prepared for the reset that they had accomplished with the brand,” he says. The director decided to use the male revue, which includes a water-drenched seduction number with a female performer, as the basis for Magic Mike’s Last Dance.

“The Magic Mike world was beginning to expand into a larger cultural conversation about men and women, about desire and fantasy, about sexuality and sensuality and eroticism,” says Soderbergh, who has become an investor in the live shows. Magic Mike Live shows in Las Vegas and London recently posted their biggest weeks of ticket sales in the history of the brand, spurred by advertising for the new movie. The live shows have run in Las Vegas since 2017 and London since 2018, with shorter engagements in Berlin and in Sydney and Melbourne in Australia.

Soderbergh estimates the production costs for Magic Mike’s Last Dance at $29m. The total budget was higher because the payment structure is different this time, with the principals compensated ahead of the movie’s release. The movie’s creators knew they wanted the story to reflect their audience, one reason a major character was written as an older woman. Hayek Pinault, 56, portrays a worldly businesswoman and mother going through a nasty divorce opposite the slightly adrift bartender played by 42-year-old Tatum.

The franchise is going gangbusters. There are discussions of Magic Mike spin-off movies, romance novels, liquor and dance classes. The team is now looking for a Magic Mike screen project led by a female writer, director or actress.

At the Miami live show at a 500-seat venue under a tent, dancers, tattooed and chest-waxed to a sheen, try to look steamy while concentrating on complex choreography. The audience is filled with a range of ages. Younger women snap selfies, grandmas treat dancers like something between a sex object and a favourite grandson and mums try to feel a little like Hayek Pinault for the $59-$94 admission price. On rare occasions, women at Magic Mike Live shows arrive without underwear or let their tops slip open.

Rani Sandhu, who has seen the show 111 times, started going to the Las Vegas revue from her home in Vancouver, British Columbia, after her mother died. Finally, something made her smile. Now the dancers know her name. “Going to the show brought back an immense feeling of joy and excitement – it evokes memories you once felt,” says Sandhu, 29, a nurse. She has no interest in going to a traditional male strip club, she adds. At a quieter moment, performers come into the audience and ask women for a slow dance. Some have broken down in tears, sharing their experience of an illness or recent loss. Others tell the men this is the first time they have been touched in years.

“I don’t tell people to go see my movies, but I will tell everyone to come see the show because I know how much joy is in it,” Tatum says. “I know the thing that’s embedded inside of it is good.”

The Wall Street Journal