Years later, it is still not clear if the new spaces will really serve the display and development of the collection or whether they will be filled up with large and vacuous pieces of contemporary commercial art. It’s unfortunate timing that the most recent acquisition of the gallery, loudly trumpeted to the media, should fit so clearly into this category.

The gallery commissioned a huge mural from Takashi Murakami for a figure that has not been disclosed but which a colleague has described in print as a “multimillion-dollar sum”. The gallery’s director writes with a kind of naive reverence of first visiting Murakami’s studio in Tokyo accompanied, unsurprisingly, by a representative of Gagosian gallery in New York, probably the biggest money-making machine in the transnational contemporary art business.

In any case this purchase is a spectacular waste of money: Murakami’s work is commercial schlock produced by an art factory, which it is hard to imagine wanting to acquire at any price.

For, unlike financial value, which can only be measured from zero upwards, aesthetic value can also be measured in negative numbers: bad art, in other words, like bad food, is not only lacking in goodness but actually bad for you.

Good art of all kinds makes us more conscious, more sensitive and more thoughtful; bad art and kitsch make us more obtuse.

Inevitably someone will cite the example of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973 for $1.3m. Wasn’t that a controversial choice at the time? But the comparison is misleading for a number of reasons, the first of which is the difference is in the quality and significance of the works, Pollock’s being one of the most important of the whole American post-war abstract movement.

Judgments of quality are hard, but they are not subjective, as so many people imagine. They are made on the basis of knowledge, understanding of art history, and long experience; and they are vitiated by fashion and marketing hype, as in this case. What helps to mitigate the effect of these distracting and corrupting influences is the passage of time: when Blue Poles was acquired, it was already 21 years old. I suspect Murakami’s work will look even more tawdry by 2040, when those responsible for its purchase are long gone.

And what else could have been done with this much money? The work is being purchased with funds from the foundation, whose members may well have hoped for something better.

This kind of money could have bought a lot of good art for the collection: for example, the record price paid at auction for a painting by Rick Amor is, I believe, around $300,000; for a photograph by Bill Henson it is around $66,000. Countless other paintings, photographs and sculptures are much cheaper; you could line whole galleries with modern or old master prints for this kind of money.

It is not easy to build a public collection responsibly and effectively. A century ago trustees and directors of Australian galleries often erred on the side of caution and notoriously passed up significant opportunities; in recent decades, spooked by the dread of being considered conservative, they have become fashion victims.

So when we read of acts of philanthropy like the recently announced $38m Ramsay bequest to the Art Gallery of South Australia to develop its collection, we have to hope that the bequest comes with very clear guidelines to save the funds from being squandered on modish, aggressively promoted and very expensive products of the contemporary art business.

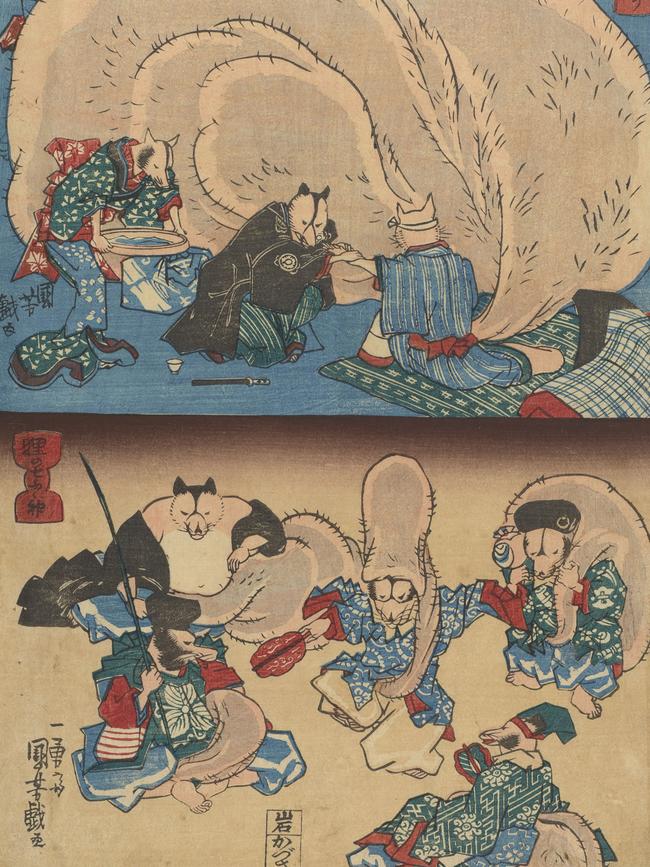

Murakami is not only represented by the huge painting that has been acquired, but by another mural and by two enormous statues. These are if possible even uglier and more kitsch than the murals: they are based on the tradition of deliberately grotesque guardian spirits that stand outside temples and shrines, but in their traditional form even these figures are beautifully made. Murakami’s versions, fabricated in his art factory, resemble models made for a commercial theme park. Murakami’s presence throughout dominates and spoils the exhibition, which is a pity, since it otherwise includes some much better work, mostly coloured woodblocks from the 19th and 20th centuries. The problem, however, is not just that Murakami drowns out subtler presences with his loudness and vulgarity but that by caricaturing themes that appear in the older work, he makes that work seem less refined than it really is, or in some cases reveals its ultimately limited interest.

For one must admit from the outset that the theme of this exhibition does not represent the highest manifestations of either Japanese art or culture more generally. I lived for many years in Japan as a child and I was familiar with this pervasive world of alternately sinister and absurd spirit beings, monsters and ghosts, from Lafcadio Hearn’s retellings of Japanese ghost stories to pictures of kappa, the turtle-demons with holes in the top of their heads; they were dangerous but stupid. If you could get them to lean forward, their brains would spill out and they would die.

But this world is far from the refinement of Zen Buddhism, ink painting, the code of the samurai, the art of swordsmanship, the tea ceremony and other expressions of a quintessentially Japanese aesthetic and philosophical vision. It does, however, survive in stories and in theatre as well as later in film, like the dark underside of that vision of lucidity and stillness.

For the monsters, demons, witches and ghosts are survivals from a more primitive animistic culture that preceded the arrival of Buddhism in its two main Japanese forms, Amidism (or Pure Land Buddhism) and Zen. That animistic culture was never entirely supplanted but persisted in the form of the Shinto cult, which deals with everything that pertains to the life of nature.

So the Japanese practise a kind of religious dualism, in which they look to Shinto for some things and to Buddhism for others. Marriage, for example, is celebrated in the Shinto rite, but death and funerals are Buddhist, so that the soul of the deceased may join Amida Buddha in the Pure Land of the next world.

But the superstitious peasants, like the peasantry in Europe in the Middle Ages, were mostly concerned with a natural world that was filled with fearful spirits and demons.

Even the urban population loved ghost stories, however, which so often spoke of the dark consequences of a society ruled by rigid hierarchical and moral standards: the ghosts of young women who had died of unattainable love or who had been abandoned by a heartless lover were popular themes, as we have seen in earlier exhibitions such as the Hanga show at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2015.

Coloured woodblock printing, or ukiyoe, began in the later 18th century and flourished in the first half of the 19th century, the time of Hiroshige and Hokusai, as well as less familiar masters such as Kunisada. Although they are technically complex and refined, these prints were produced in considerable numbers and covered many subjects, particularly portraits of famous courtesans, genre scenes and landscapes.

Ghost stories were also popular, as were erotic and horror subjects. Here it is especially stories of ghosts, demons and witches that we encounter, and one of the interesting aspects of the exhibition is to watch the appearance of Western influence after the forcible opening of Japan after the middle of the 19th century.

In reality the ukiyoe genre already incorporated Western influences, especially in the form of perspective, which is why the later Western discovery of ukiyoe in the time of the Impressionists is such an exceptional instance of cultural exchange: the West discovers and adapts a representation of space that was itself a Japanese adaptation of a Western form.

But these early Western influences have been fully integrated in the work of the ukiyoe masters of the first half of the 19th century, and their style seems all of a piece. In contrast, the work of the second half of the century very rapidly shows evidence of a renewed Western influence, and that element only becomes more conspicuous towards the end of the century. This phenomenon is itself interesting, for it represents the desire by the artists to incorporate new elements of naturalism into their style, but at the same time it reflects a loss of confidence in the tradition they have inherited, so that these works are imbued with a sense of anxiety and uncertainty about the legitimacy of their own vision of the world.

There was of course a similar anxiety in Japanese society at large as the country opened itself to Western influence and then, under the Meiji Restoration, undertook a radical program of reform and Westernisation that undermined some of the most important aspects of traditional Japanese culture, especially the role of the samurai class. It would thus be interesting to know if the production of ghost and other supernatural images increased in the last decades of the century: the proportion of later, increasingly Westernised images in the exhibition suggests that they proliferated, in this newly naturalistic form, as an expression of the deep stresses of the society of the time.

Ghosts and other subjects that had always been subjects of superstitious dread could quite naturally serve to express the growing malaise of a society in transition, just as the science fiction and thriller genres are used by Hollywood today to make films that address the paranoid or apocalyptic fears of a modern mass audience.

But these images designed to express, excite or assuage the confusions and anxieties of a Japanese mass audience a century and a half ago are not ultimately great masterpieces of art. This is nothing like the NGV’s Hokusai exhibition in 2017, which was the comprehensive survey of a great and influential artist.

In the end, the themes of these images are repetitious as well as sensational, leaving us a little jaded. And we may well be uncomfortable with the recurrent theme of old crones turning into evil witches and demonesses.

This deep dread of the dark side of the feminine is found in many cultures, but it feels a bit too close for comfort to our own witch crazes of the 17th century.

Japan Supernatural

Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, to March 8

Building is at last beginning on the Art Gallery of NSW’s much-criticised extension, burdened with the awkward name “Sydney Modern’’. I was present at the press launch of this project many years ago, and although I had no preconceived view at the time, I was disturbed by the almost complete lack of any reference to art. We heard a lot about visitor numbers, or what were curiously referred to as “visitations”, but we could have been talking about an airport or a shopping mall.