Scathing condemnation of cronyism and venality

How much worse have things gotten in Africa’s most populous country? It turns out there is a lower circle of hell to explore.

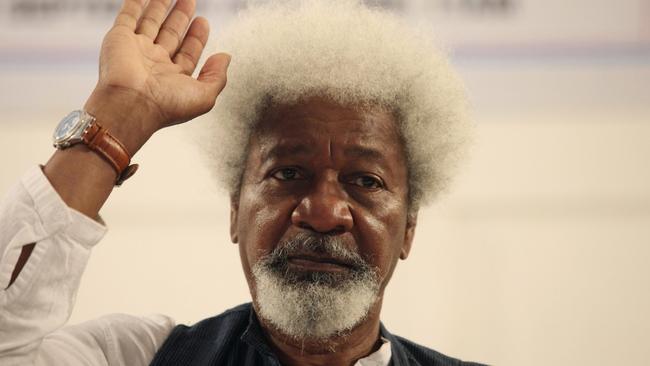

Poet, playwright, essayist, activist, first sub-Saharan African to win the Nobel prize for literature in 1986, thorn in the side of successive strongman regimes throughout his home continent – Wole Soyinka is the most garlanded and revered figure in African letters.

After campaigning for independence from British colonial rule in his native Nigeria, the writer was imprisoned and held in solitary confinement for two years during that nation’s subsequent civil war. Two decades on, Soyinka was condemned to death in absentia by kleptocrat Sani Abacha after fleeing Nigeria by motorcycle. The skin colour or religion of his political antagonists has been of little matter to the writer; the corruption and cruelty of their various regimes, however, has been a central concern.

So when, during the recent pandemic lockdown, Soyinka was moved to write his first novel in almost five decades, responding to what he called “one of the most pessimistic years” in his nation’s history, readers could be forgiven for wondering how much worse things could have gotten in Africa’s most populous and dynamic country. Chronicles From the Land of the Happiest People on Earth reveals there is always a lower circle of hell to explore.

Chronicles represents a scathing condemnation of cronyism and venality, social manipulation and human exploitation in a society – a barely fictionalised Nigeria – riven by economic inequality and ethnic tensions. In these pages, Soyinka lays about with the lordliness of a man related to Yoruba royalty, along with the vigour of one much younger than his 86 years.

While the novel’s language is satirical in the extreme – a kind of tortured, circumlocutory Edwardian English – its viewpoint is wide-screen and utterly modern. This is a vision of contemporary Africa closer to the paranoid panoptic of Thomas Pynchon, say, or the wounded civic idealism of Saul Bellow.

The result is perplexing and somewhat chaotic: a state-of-the-nation novel about a country too big and brash to be easily contained by any literary form. Surprisingly, perhaps, it is also one that resolves into a story of ritual and regeneration. A conservative turn towards pre-colonial social and cultural forms, in other words: the restatement of a distinctly Yoruba metaphysics.

The official world explored by Chronicles, it should be noted, has no truck with tradition whatsoever. Initial chapters introduce us to Papa Davina, a brilliant fraudster who returned from jail time in the US with a powerful sense of how religion can be used to gull the credulous and enrich its figureheads.

Davina’s invented, syncretic religion – a dash of evangelical Christianity melded with Islam and local traditions – becomes something of a state creed in a nation where questions of belief are both powerful drivers of conflict and fig leaves for sexual abuse and political graft.

Such opportunistic ecumenism fits perfectly with a national political leadership – at whose head sits the ruthless and mercurial Sir Goddie – that runs the country like a reality TV show while implicating itself in a network of criminality so vast the line between corrupt practice and exercise of state power has dissolved. It is against this tentacular creature that Soyinka’s heroes pit their decency.

Doctor Menka is a senior and widely respected surgeon, firmly ensconced with the country’s political and financial elite in an old colonial club where he keeps rooms. But when he becomes aware that his hospital and, indeed, many others throughout the land have been infiltrated by gangs involved in organ trafficking, Menka enlists the help of his old school friends, the ‘Gong of Four’ as they facetiously called themselves in innocent youth, who have risen like him to positions of authority.

When one member of the quartet vanishes and another is terrified into silence, Menka is left with no ally but his closest friend, Duyole Pitan-Payne – an engineer and entrepreneur of great wealth, charisma and vitality – until even that national treasure is targeted in an assassination attempt and eventually dies in an Austrian hospital. The most moving sections of the book narrate Menka’s increasingly desperate efforts to have his friend repatriated for burial on home soil, despite mysterious resistance from the Pitan-Payne clan.

But the respect and care he shows for Duyole’s body comes to stand for something far larger. Menka’s lonely attempts to ensure a proper ritual, his insistence on the sanctity of the human body, are inimical to the trade in body parts aided and abetted by the country’s leadership, whose greed outweighs all moral considerations.

Soyinka’s novel may be the baggiest of baggy monsters, straining at the seams to contain the society it depicts, but the author’s anger and outrage, his pitting of social commitment against brute ideology, possess absolute clarity. It is for the body (and, for Menka at least, the soul) of an entire nation that the battle is being fought.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

Chronicles From the Land of the Happiest People on Earth

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout