Review: There is a Certain Slant of Light, Castlemaine Art Museum

Creating paintings that leave a lasting impression often depends on the light – as this exhibition so clearly shows

The title of this exhibition, There is a Certain Slant of Light, comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson, although if you read past the first line, the “slant of light” turns out to be “oppressive” rather than elegiac, and that is not particularly relevant to the show. But the idea, in itself, is quite a good general way to present a selection of pictures from the collection because it reminds us of the importance of lighting in any kind of painting that seeks to give some sort of account of the world of appearances.

In the first place, of course, the world is only visible to us through light. Reflected, received by the eye and coded by the visual cortex, it becomes what we have grown accustomed since infancy to understand as the real world. We can even predict many of the tactile qualities of things from their visual appearances because of long experience and association.

As far as painting is concerned, the arrangement of light and shade is important for several complementary reasons. First of all, it allows the painter to model figures and objects to give them volume and to establish their position in space. Then, more broadly, it can unify all the parts of the composition, give prominence to the more important elements and consign secondary parts to the background.

It can be used narratively or dramatically to draw attention to a certain part of the picture or, more generally, to create mood and emotional tone. In painting from life, especially in the landscape, the fall of light depends on and, in turn, defines the time of day and orientation of the point of view on the axes of the compass.

The importance of light in landscape explains why this is almost the first thing a landscape painter thinks of after selecting and composing the motif itself. In figure paintings, where the fall of light is more at the discretion of the artist, it is still the most important decision to make after, or preferably with, the arrangement of the figures themselves. Caravaggio was criticised for painting in an underground studio where the light always fell from above in the same way, but this suited his dramatic, seemingly naturalistic, but also artificial compositions arranged in shallow space. Other artists, such as Tintoretto and Poussin, made wax models of the figures in their compositions, arranged them in boxes and experimented with the direction of light and the position of the figures until the result was a satisfactory whole.

The first picture in this exhibition, Tom Roberts’s Reconciliation, painted in 1887, and given to the gallery by him in 1930, the year before his death, is a fine example of the narrative or dramatic use of light. Both heads are very good, but the compositional emphasis as well as the fall of light draw our attention to that of the woman, whose complex, subtly nuanced expression shows that the discord had arisen on her side, and that although she is now appeased, the vestiges of her anger or pain have not been completely effaced.

The following short wall has three paintings, two by Frederick McCubbin and one by Arthur Streeton, a late picture that uses the fall of light in a semi-narrative way to emphasise the features for which the site has been called Buffalo Mountain. The most memorable of the three pictures is an early work by McCubbin in which a boy is walking home to his cottage in the country at sunset.

This wall is at one end of the room. The two long walls face each other and effectively make up most of the exhibition – they are thoughtfully arranged, not only in the many interesting juxtapositions that reward the attentive visitor, but in the way that the work has been divided into two clear groups.

On the far wall are pictures painted in natural light and en plein air, while on the near wall – closer to the entrance – are ones painted either by artificial and, therefore, constant light, or with imaginary or theatrical lighting.

The first of these, although separated from the main section of the wall, is Emmanuel Phillips Fox’s Bathing Hour (1909). It is a sunny day, and judging by the short shadows, bathing hour is either late morning or early afternoon. The brightness is mitigated by the fact that the principal figures in the foreground, a mother and her baby daughter, are standing in the shadow of a tree. The child, seen from the back, is naked but not because she is bathing – all the bathing children are fairly well covered – but because she is changing after her swim.

Next, there are three small but charming pictures by Fox’s wife, Ethel Carrick Fox, two in France and one in Venice. In each case, light defines the time of day and evokes mood, as well as picking out the defining architectural features of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice (it must be afternoon because San Giorgio faces northwest).

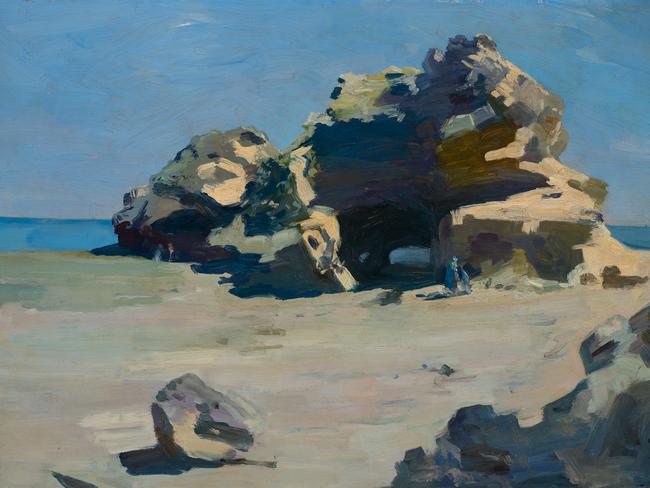

After this is the first of several interesting juxtapositions: a plein air sketch of water and rocks in the south of France by E.P. Fox, and a view of a rock formation called London Bridge on the ocean just outside Port Philip by Arthur Boyd’s uncle, Penleigh Boyd, a talented painter who died in a car crash in 1923, aged 33.

Fox’s picture is painted in the French Impressionist style which he – unlike Roberts and Streeton – had learned, while Boyd’s is more broadly and decisively brushed, defining structure rather than seeking to capture ephemeral effects of light and atmosphere.

But this picture, in turn, forms an interesting contrast with another larger work by the same artist hanging next to it, a view of Frankston before it was overrun by low-rent suburbia.

The foreground of this picture has character, but the background and especially the sky and water are surprisingly bland. The difference seems to be that the first picture was quickly and energetically captured in the moment, seizing specific and strongly defined effects of light and shade, while the second was worked over for too long and seems to have averaged a succession of changing and distinct conditions into a bland generic image.

After this are three fine little paintings by Clarice Beckett. She would go out very early in the morning to capture these views of Port Philip Bay near her family home at Beaumaris. As I have previously suggested, each morning’s work was like a practice of meditation, focused on the moment at which the world becomes visible again after night, and the short interval during which colour returns, emerging from darkness, but has not yet reached its full saturation.

Beckett was also intrigued by the beginnings of human activity, fishermen putting out to sea and other signs of life that she watched, always the observer, from a distance. In the first, one of the finest of these little studies, a man in a white shirt stands on a jetty; in the second, a little figure pushes a boat out into the bay; and in the third, a couple of shadowy men are just visible on a yacht. In the foreground of this picture, incidentally, Beckett has left the bare cardboard to represent the sand of the beach.

Here, too, there is an interesting contrast between Beckett’s approach and that of her fellow Meldrum pupil, Archibald Colquhoun, whose view of a river hangs next to her beach. Colquhoun’s brushwork is much more marked and vigorous, which could be interpreted as the difference between a masculine and feminine sensibility, but which also no doubt reflects the fact that she is painting at a time of day when conditions really are soft and ineffable, while he is painting in full daylight, albeit on an overcast day.

The opposite wall again starts with a painting by Beckett, but this time a vase of flowers, a subject painted indoors and under artificial and thus constant light. This picture is very characteristic of the Meldrum method in its striking, almost photographic naturalism, offset by a generally blurry finish. The method tries to capture appearance with “scientific” accuracy, but the distance from which the picture is painted rules out the superficial naturalism of photorealism.

This picture is unexpectedly but suggestively set against one by Jeffrey Smart with children playing among disconcerting and unidentifiable industrial forms. What they have in common is that the lighting is artificial, not natural. In Smart’s case, it is imagined and expressive, conjured from his imagination, picking out the brightly coloured metal objects against one of his characteristically dark skies.

Two more of Meldrum’s pupils and the master himself come next: first, an interior by Percy Leason with two of his children, and then Polly Hurry’s portrait of Ursula Hoff, the legendary curator of the NGV, who set a standard that her successors have been unable to match. This portrait also illustrates the curious way that the Meldrum method often captures subtleties of the sitter’s character while ostensibly pursuing only optical realism.

Meldrum’s own painting is a deceptively simple one that turns out to be far more complex than it seems. Interior (1950) appears to be a view of the artist’s sitting room or studio, with chairs, a table and a painting on the wall, which looks like one of Meldrum’s own portraits: a figure leaning to one side like his picture of John Farmer (1936) – Polly Hurry’s husband – except that the colours are wrong. This self-referential motif of the painting within a painting, an example of so-called mise-en-abyme composition, is interesting enough in itself. But when we know a little more about his process, we realise that Meldrum would have painted this picture in its frame, while looking through a similar adjacent frame at the view of the room, thus ensuring that his painting was an accurate visual account of what he saw from a certain distance. In this perspective, the frame within the picture becomes a implicit reference not just to the artist’s work but to his process.

This painting, in turn, is, interestingly, hung next to one of Rick Amor’s mysterious interiors, set in a kind of imaginary museum, like something inspired by the writings of Borges. A few figures walk through the vast and gloomy hall of the institution. The only illumination is from a skylight on the upper left, which reveals a massive, enigmatic and faceless figure of an ancient sphinx, seen through a screen of columns.

The parallel with Meldrum is unexpectedly suggestive. In both, the slant of light is important but artificial – again one controlled, the other imaginary – but while Meldrum uses light to render mysterious what is ostensibly obvious, Amor devises an artificial illumination to give tangible reality to a fictional world that is entirely imaginary and almost metaphysical.

There is a Certain Slant of Light, Castlemaine Art Museum, until March 5.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout