Rembrandt’s skill of biblical proportions

Rembrandt took the art of printmaking to a new level of intensity, as powerful as anything he could have done in painting

The 17th century is considered a golden age of art in many parts of Europe, especially in countries outside Italy; for this was the period when the mainstream of modern art, which had been predominantly Italian for 300 years, spread spectacularly to other regions, in particular to Flanders, Holland, France and Spain.

There was no doubt that Rome, around 1600 and for the next few decades, remained the capital of modern painting, sculpture and architecture. Almost all of the most important European artists of the period spent some time in the city to absorb the lessons of antiquity, of the high renaissance masters Raphael and Michelangelo, and of the great contemporary figures Caravaggio and Carracci. Some, such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, stayed there; others, like Rubens and Velazquez, returned to their native lands; and a few, including Rembrandt, had to glean a knowledge of the great tradition at second hand.

Each of these giant figures, however, interpreted the modern heritage in a different way, drawing on and adapting their native traditions as well as imprinting them with the new lessons of Italy.

One of the most remarkable things about 17th century art is indeed the profound diversity, in spite of common elements, between France and Flanders, Holland and Spain.

This diversity reflected, among other things, the difference between the social, economic and political environments of each country, including its official religious allegiance at the time of the Counter-Reformation and of open war between Catholics and Protestants. All of these factors could have a profound effect on the place of art in a particular society and on the relation of artist to patron or to art market.

Thus Rubens was the painter to several monarchs as well as to religious orders, all of whom were eager for large and sumptuous altarpieces and narrative pictures. Velazquez worked almost exclusively for one ruler, the king of Spain. Poussin and Claude sold their pictures to private connoisseurs and collectors. And Rembrandt, in Protestant and republican Holland, without the opportunity for sumptuous royal commissions (although he painted an important series for the Prince of Orange), in a prosperous bourgeois society, but one that frowned on splendid ecclesiastical decoration, worked mainly for wealthy individuals and corporations.

Many of Rembrandt’s greatest paintings were accordingly portraits, a genre considered secondary elsewhere. This led him to concentrate on exploring the humanity and complexity of his sitters, including and perhaps most conspicuously himself, in the greatest series of self-portraits in the history of art.

Rembrandt also transformed the group portrait, a staple of Dutch corporate culture, from a mere line-up of likenesses into a collective human drama capable of rivalling history painting in depth.

It is no doubt his emphasis on subjective experience and inner feeling that led to the most striking formal aspect of Rembrandt’s painting, his intense and dramatic use of chiaroscuro, sometimes casting the greater part of a composition into shadow to emphasise the central motif, as though picked out by a spotlight. And this use of light and dark is also central to an understanding of his etchings, the art of which he was the supreme master, and which are the main focus of a fine exhibition at the NGV.

Etching also gave Rembrandt the opportunity, albeit on a smaller scale, to deal with great history subjects, especially scenes from the Bible, which were acknowledged as the highest genre of art but which, because of the circumstances of his time and place, he had few opportunities to realise in paint. They were also evidently addressed a public avid for such narrative subjects, especially perhaps in the uniquely dramatic and intense way that Rembrandt presented them.

To appreciate the distinctive aesthetic qualities of any art, it is helpful to have some understanding of the techniques and materials employed. This is especially true of prints, perhaps because while everyone has at least attempted drawing and painting as a child, exposure to printmaking rarely extends beyond a linocut lesson at school.

Linocut, which is a modern and simplified form of woodcut, belongs to the older of the two main forms of printmaking, known as “relief”: the design of the print is drawn onto a block and the surface is cut back around that design; the block is then inked and it is the remaining part of the original surface of the block that produces the image. This kind of print has a distinctively black and white pattern effect with little intermediate tone, a vivid but stylised aesthetic that was widely adopted for the illustration of children’s books in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The other main kind of printmaking – leaving aside later inventions such as lithography – is known as “intaglio”, from the Italian verb intagliare, to cut in or carve. The word is cognate with “tagliatelle” and pronounced with the same semi-silent “g”. This kind of print is generally made with a copper or zinc plate; the design is similarly carved into the surface, but the logic of the process is the reverse of a relief print.

Instead of cutting away the surface of the block around the figure, lines or grooves are cut into the metal plate; when the plate is subsequently inked, wiped back and put through the roller press, it is the ink that remains in the grooves that prints onto the paper. Hence a fundamentally different aesthetic: instead of a black and white pattern, intaglio produces an image composed of lines and hatching, articulating tonal gradients.

The oldest form of intaglio print is engraving, where all lines are cut from the copper plate with a burin: the greatest engravings by Albrecht Durer, including Melencolia I (1514) and The Knight, Death and the Devil (1513) were made in this way, as well as masterpieces by such other great engravers as Goltzius. Absolute clarity of articulation is combined in these works with an almost infinite subtlety of tonal modelling, achieved through different kinds and patterns of linework.

Rembrandt, however, used a technique known as etching. Here, instead of cutting directly into the plate, the artist covers it with an acid-resistant ground and then scratches the design into this protective surface; the plate is then submerged in an acid bath, and the acid bites into the surface of the copper where it has been exposed, creating lines or grooves. This technique requires far less physical strength and indeed technical virtuosity, so that while engraving was a specialist craft, etching was and remains far more accessible.

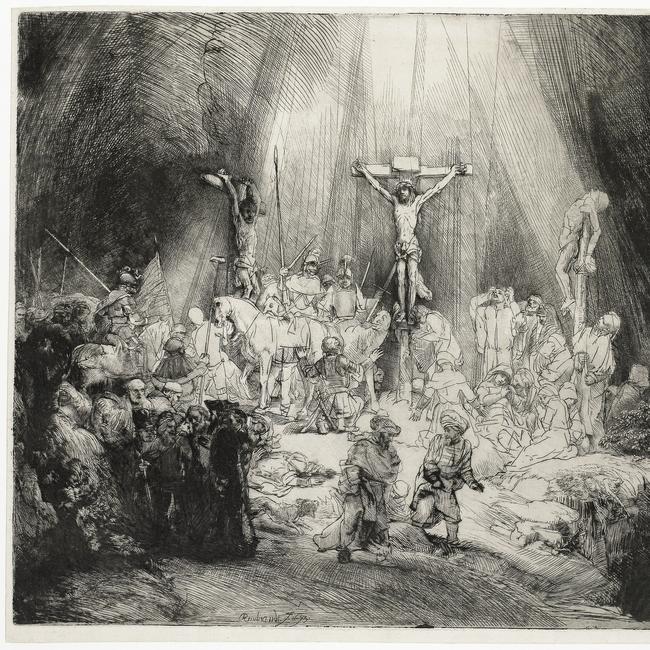

The lightness of the scratching also allows for a free and sketchy line, and we can see that from his earliest self-portraits to his landscapes, Rembrandt revelled in this potential for energy and spontaneity. Two particular masterpieces in this exhibition are Saint Jerome (c. 1653) and Abraham’s Sacrifice (1655), which illustrate both the linear and the tonal expressiveness of the medium. But the other thing that Rembrandt clearly loved about etching is the way that it allowed for the image to be changed and revised. Both quite modest prints and some of his most ambitious, such as Christ Presented to the People (1655) and Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves (1653), exist in different versions known as “states” and, as in any serious exhibition of Rembrandt prints, these states are shown side-by-side for comparison.

Making a change to a plate entails re-coating it and repeating the whole process. The easiest and most obvious changes to make are additions – either adding further details to the composition or, in many cases, building the dramatic chiaroscuro, although this is often done with drypoint, which means scratching directly into the plate without the use of acid.

One reason for making such changes is that while the engraver can see the pattern of lines incised into the plate quite clearly before inking and printing, the etcher cannot. There is always an element of working in the dark and only finding out what you have done after taking an impression.

But the most interesting changes from one state of an etching to another involve removing and replacing parts of the image. This is not possible in engraving, where the lines are cut too deeply and decisively. It is possible in etching, but particularly so in drypoint, where the lines are shallow and much of the ink is held in the burr that is thrown up beside the line and is easily worn down in the printing process. So the most remarkable examples of radical transformation of images – where we can feel the artist consciously exploiting the malleability of the process – can be found in a couple of late and very big works, executed entirely in drypoint.

Two versions of Christ presented to the people are presented side-by-side, representing the fifth and the seventh states. In the earlier image, a large crowd fills the foreground, the crowd to whom, as the label reminds us, Pontius Pilate is presenting Jesus; the effect is largely linear and the tonal range is subdued. In the later version the crowd, with much of the anecdotal detail, has been erased, and the tonal range of the plate has been greatly increased by surrounding the central scene with dark shadow.

And yet there are still elusive reminders of the erased figures, like a printmaking version of what is called a “pentimento” in painting. And this effect is even more pronounced in the image of the Crucifixion, where we can compare the third and fourth states of the image. The earlier version is already intensely expressive and characterised by powerful effects of light and dark, but the fourth takes chiaroscuro beyond theatrical drama to a level of metaphysical sublime.

Once again all incidental detail is removed; huge areas are overwhelmed by shadow, and the bad thief, on Christ’s left, is now absorbed into the invading blackness. Saint Longinus’s horse has been turned around to face inward, and the saint himself, kneeling on the ground originally, is now mounted. Of the two figures in the foreground, one has been reduced to a shadow and the other strengthened. Rembrandt has taken the art of printmaking to a new level of intensity, as powerful as anything he could have done in painting, in this evocation of an epochal moment in the history of mankind.

It is a credit to the National Gallery of Victoria – with the generous funding of the Felton Bequest – that it has built such an important collection of masterpieces, notably in the field of works on paper. Today the Gallery has the opportunity to purchase another etching by Rembrandt, a portrait of the apothecary Abraham Francen in his study, examining a large print and surrounded by other works of art in his collection. The work is included in the collection, and funding is currently being raised through the Rembrandt 2023 Appeal.

Rembrandt: True to Life

National Gallery of Victoria until September 10

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout