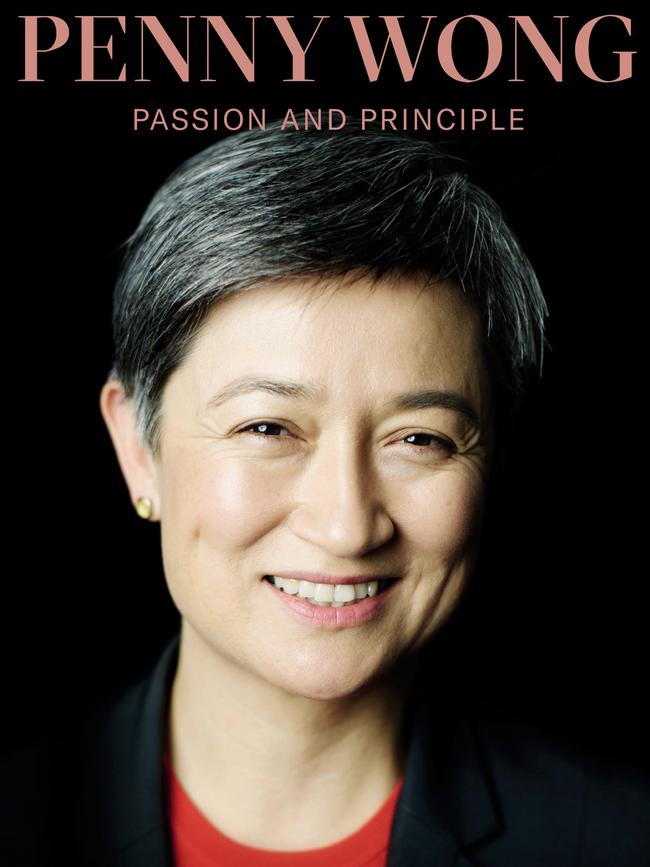

Progress of an Aussie battler

A new biography reveals the excruciating reason Penny Wong learned to keep her famous cool.

How does a researcher write a biography when the subject doesn’t want to participate in the process, let alone see the book published? Margaret Simons is an award-winning journalist of 13 books, including an acclaimed biography of Malcolm Fraser, but even she had to exercise extreme diplomacy and patience when negotiating with the intensely private and guarded Penny Wong.

Many readers will remember the rare sight of Wong expressing deep emotion when the Yes vote for same-sex marriage was passed in parliament, bursting into tears and burying her face in her hands, but most of the time she presents as a formidable, serious and unflappable politician.

Now opposition spokeswoman for foreign affairs and leader of the Labor Party in the Senate, Wong’s trigger for joining the party initially was to combat racism.

At the time, then-opposition leader John Howard had launched a new immigration policy for the Liberal-National Coalition called “One Australia”, the implementation of which would slow and possibly halt Asian immigration.

Later, at the age of 33, Wong was elected to the Senate, becoming one of the first Asians and the first openly gay woman in a representative body in the history of this country.

Penny Wong was born in North Borneo in 1968 to an Australian mother, Jane Chapman, and a Malaysian father, Francis Wong, who is of Cantonese descent.

Her parents had met in Australia in the early 1960s, when Francis was studying architecture at the University of Adelaide. The couple married but after Francis graduated they were forced to move back to Borneo because the White Australia Policy made it difficult for them to live as a married couple in this country.

Her father became a successful property developer and local government councillor. Another child was born, Wong’s brother, Toby, but by 1976 Wong’s parents had separated amicably and her mother had moved back to Adelaide with the children, settling in an all-white neighbourhood.

The racism that she and her brother experienced was excruciating.

“Go back to where you came from, you slant-eyed little slut!” called a neighbour from over the fence. Toby was taunted by a group of boys and thrown off a bus by the driver, and at home their driveway was graffitied with racial slurs.

The great irony of the racism Wong and her brother endured is that their mother’s side of the family is descended from the first shipload of immigrants to settle in South Australia, in 1836.

Aimed at another individual such constant abuse might have produced an aggressive and destructive juvenile delinquent, but instead Wong learned to control her emotions and develop a steely, long-term resolve.

She won a scholarship to the eminent Scotch College and excelled academically, creatively and athletically, graduating as dux of the school.

Apparently, the subject Wong was most ambivalent about in the context of this biography was that of her beloved brother, who was far more sensitive and fragile than his assertive older sister.

An accomplished chef and consultant to several Melbourne gastropubs, Toby developed a drug addiction and committed suicide in 2002. She addressed this heartbreaking loss during her maiden speech in parliament, announcing that Toby had “turned 30 on the day I was elected to this place, and died 10 days later … Your life and death ensure that I shall never forget what it is like for those who are truly marginalised”.

Since then, Wong seems to have kept her promise, but by playing a long game rather than imploding with emotional political tantrums.

Initially, in 2004, she stunned her supporters by honouring official Labor policy that voted against same-sex marriage. However, if she’d crossed the floor and had voted against the policy, she’d have risked being expelled from the party, and she knew that being “outside the room” would have stripped her of all possible future influence.

The emotional control and steely resolve she’d developed as a child has served her well during times of political conflict. Simons has noted that Wong’s favourite term is “Praxis”: practical political action in the quest for change.

Wong quickly became Labor’s most successful and articulate attack dog, transmuting the earnest analysis of figures and data into savvy political bon mots. She also used her quick tongue to counter racial vilification.

During the 2004 election campaign, Wong and two young male Labor campaigners were sitting outside a suburban Adelaide shopping centre when a woman appeared and yelled out to her: “How does a slanty-eyed slut like you get two guys?” Wong didn’t miss a beat: “Just lucky, I guess.”

Later, Kevin Rudd appointed her as spokeswoman for the 2007 election campaign. After a historic win for Labor, he named her minister for water and minister for climate change, and Wong was responsible for pushing through the water buyback scheme. Even though she exhausted herself juggling both positions, she has since admitted that the dual portfolios were too heavy a load for one politician.

In the final three years of the most recent Labor government, Wong was minister for finance, during which time she was calm and restrained during the Rudd/Julia Gillard backstabbing and leaking rituals, refusing to criticise either of them in public.

After Labor’s unexpected loss in the 2019 election, Wong considered quitting politics, but obviously has since changed her mind. Allan Gyngell, director of the Crawford Australian Leadership Forum, maintains that Wong is probably the best-prepared foreign minister-in-waiting Australia has ever had.

And would she ever run for leadership of the Labor Party and consequently tip her hat for the coveted top job? Sadly, Wong doesn’t think Australia is ready for a gay, Asian, female prime minister.

In 2007, Wong fell in love with her now long-term partner, Sophie Allouache, who four years later gave birth to their first daughter, via a sperm donor who lived in NSW. A second daughter followed, via the same donor, and the hate mail generated by their non-traditional family apparently continues until this day.

Given the homophobia, sexism and racism that Wong has suffered throughout her political and private life, it’s understandable that she would be reticent about a researcher trawling through the minutiae of her past, but what Simons has excavated from the background of this extraordinary Australian should be cause for great pride and celebration.

Mandy Sayer’s most recent book is Misfits & Me: Collected Non-Fiction.

Penny Wong: Passion and Principle

By Margaret Simona

Black Inc, 372pp, $34.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout