Prisoners in a foreign land

A moving exhibition documents the harrowing experience of a group of German men who were shipped to Australia in 1940.

This exhibition tells the remarkable story of German men and boys first detained in Britain as enemy aliens at the outset of World War II and then sent to Australia for internment as a security measure. It is the result of long-term and patient research of the kind that could perhaps only be carried out by the staff of a library: building collections of primary material, gathering evidence and documentation, pursuing leads and seeking out the testimony of survivors and their families.

This was not the first time that Germans had been interned as enemy aliens, of course. Readers may recall another outstanding exhibition held at the Museum of Sydney in 2011, The Enemy within (reviewed here in July 2011). This show, which was based on a recently rediscovered archive of photographs by a young Bavarian, Paul Dubotzki, offered a fascinating and moving insight into life in the detainee camps at Holsworthy, Berrima and Trial Bay during the years of the Great War.

The Enemy within ultimately told a story – one could add an exemplary story – of traumatic social disruption and of the extraordinary resilience that rebuilt social and cultural structures within a matter of months. The camps were filled by men taken from their families and homes, their occupations and their vocations, and thrust into hardship, boredom and confinement. Some were demoralised; criminal elements began to exploit the social fracturing.

But then the body politic, so to speak, reconstituted itself, the criminal elements were suppressed, autonomy was demanded and obtained from the authorities; and soon schools, workshops and orchestras were functioning even within the concentration camp environment.

We find the same kind of cultural resilience in the present exhibition, although the circumstances were different in several important respects (including the fact that the internment in this case was for a much shorter period, around 18 months). In the first place, the Germans rounded up in World War I, apart from some officers and men captured on German merchant ships and the light naval cruiser SMS Emden, were long-term residents of Australia, including professionals and industrialists – a reminder, in fact, of the significant German migration to Australia in the second half of the 19th century and of the prominence of Germans in academic and other fields at the time.

The men who came to Australia on HMT Dunera in July 1940 had never been to this land before. Some were British residents, but most were refugees, many Jewish, from the rise of the Nazi party in their homelands. The vast majority were therefore anti-Nazi and after their release many volunteered to join the Australian armed forces or the British army or intelligence organisations. Among these was Sigmund Freud’s grandson Walter (1921-2004) who returned to England in October 1941, where he joined the Royal Pioneer Corps and then in 1943 the Special Operations Executive (he was involved in a daring parachute mission behind enemy lines in 1945); after the war he served in the War Crimes Investigation Unit.

Walter Freud was only 19 when he came out on the Dunera; the men on the ship were aged between 16 and 66, and represented a range of social classes and levels of education, including artists, scientists, lawyers – even two judges – doctors and scholars. They were very poorly treated on their voyage out to Australia. The Dunera was loaded far beyond her capacity of 1600 as a troop carrier and 2546 men were held, mainly below decks, in appalling conditions of crowding and inadequate sanitation. They were also mistreated by their guards, who must have been largely from the dregs of the military to be assigned to the supervision of unarmed civilian transportees. A court-martial was later held in which several guards were disciplined or dismissed, and compensation was paid to the passengers for property lost or destroyed.

But things could have been much worse. A German U-boat fired two torpedoes at HMT Dunera in the Irish Sea; one missed and the other, almost miraculously, glanced off the hull without detonating. If the torpedo had exploded, the men aboard could all have perished, like the crew and passengers of so many ships struck by German submarines during these years.

They arrived in September 1940 emaciated and in a pitiful condition, but were much more kindly treated by their Australian guards; 545 were disembarked in Melbourne and taken to camps at Tatura, near Shepparton in Victoria, while the others continued to Sydney and were initially taken to Hay, in the far west of NSW (a photographic wall installation evokes the remoteness of the location); later, in May 1941, the detainees at Hay were moved about three hours’ drive south to Tatura, which was, as we are told, “a more suitable location with a milder climate and generally more agreeable surroundings”.

Life in an internment camp was inevitably confined, constrained and boring, but at least the detainees were allowed to organise their own internal affairs, and so, as we learn from the exhibition and its accompanying booklet, they elected camp leaders and hut captains to maintain order and discipline, and soon they had set up libraries and “schools offering a wide range of practical and theoretical classes and lectures in more than a hundred subjects; they ran artist workshops, discussion groups and debates, formed choirs, held art exhibitions, theatrical performances and musical recitals”. Art history lectures were given by Franz Philipp (1914-70), later professor of art history at the University of Melbourne. There is an impressive German translation of Waltzing Matilda in the booklet.

The inmates at Hay even designed their own camp currency, and although this was soon prohibited, examples are included in the exhibition.

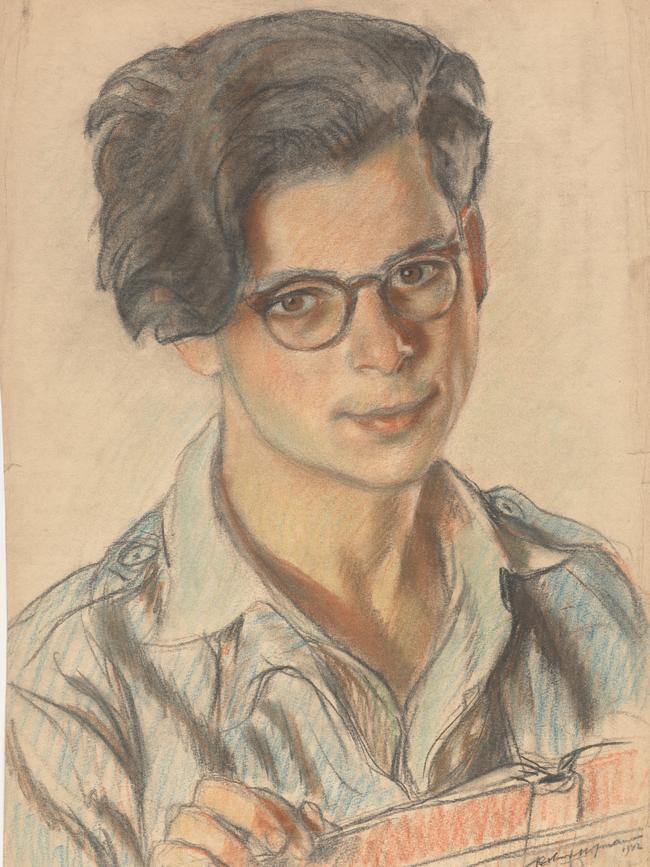

By good fortune, the Dunera group included a number of talented artists, whose work illustrates both the physical environment of the camps and, above all, the human experience and personality of the detainees. The exhibition opens, indeed, with an extraordinary wall of portraits by Robert Hofmann (1899-1987), who had been classically trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and, though Jewish, an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I. Among the most sensitive of these is the profile of the young Rabbi Hans Elchanan Blumenthal (1915-95), who later became Principal of the North Bondi Hebrew School before moving to Cape Town and later to Israel.

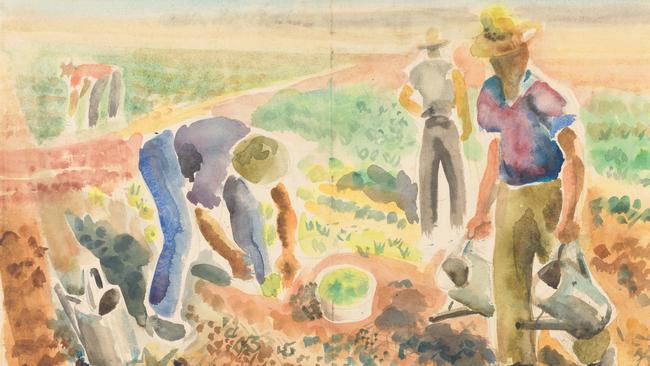

Erwin Fabian (1915-2020), who later settled in Melbourne and practised sculpture to the end of an exceptionally long life, was much younger, but left many vivid sketches and watercolours of camp existence, including several reproduced in the exhibition booklet: from a pencil sketch of fellow passengers asleep in hammocks during the voyage out to a view of camp huts behind a barbed-wire fence at Hay under a darkening sky, and happier watercolours of internees laying water pipes or working in the camp’s vegetable gardens on a sunny day. In the watercolour Camp after rainfall, the yellow-painted huts are poetically reflected in broad sheets of water.

Interestingly, Fabian never liked to talk about this period of his life in later years, perhaps because it evoked traumatic memories – not so much of the voyage and camp life but of the loss of so many relatives and friends murdered by the Nazis – and because he did not like to be classified as one of the “Dunera boys”, as the group later came to known. This appellation conjured up a number of connotations, perhaps especially of being foreign and an outsider.

Another artist reluctant to discuss this part of his life was Paul Mezulianik (1921-2019), who was born in Vienna and escaped to Britain in 1939 with help from a Quaker group. He returned to England in 1942 and worked first in an aircraft instrument factory, and then in film and advertising. He refused to discuss his experience of internment, and the drawings here exhibited, long hidden away, were only discovered by his stepdaughter a month before his death at the age of 97. He never knew that these sketches, of fellow artists or art students, possibly in a life drawing class, had been brought back to light.

One artist who later changed his name to avoid the connotation of foreignness and perhaps especially the association with Germany in the aftermath of the war, was Georg Teltscher, later George Adams (1904-83), who studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar and fought in the Spanish Civil War in 1936 before moving to London in 1938. It was he who won the competition to design the camp currency at Hay. He later returned to England to design propaganda leaflets, worked at MIT, and taught in Nigeria before finally retiring in London. Very few of these men in fact ever returned to Germany or Austria after what they and their families had suffered.

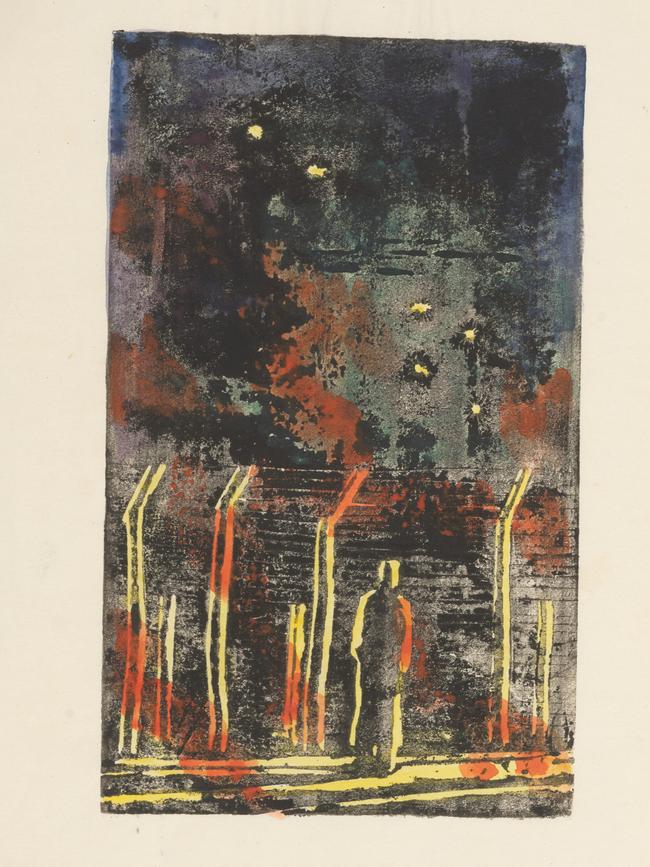

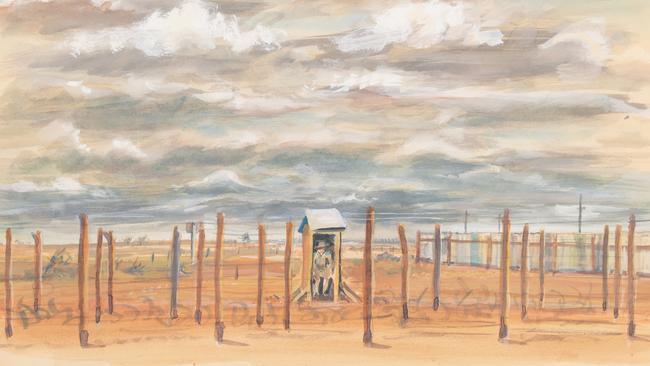

Teltscher is represented in the exhibition by many evocative images of the camp at Hay and its flat landscape ringed by fences. The fence posts become strangely poetic in a moonlit nocturne; they are more matter-of-fact in a daylight view in which a sentry sits in a box surrounded by fences extending on both sides to the edges of the composition, under the same streaky clouds that appear in the nocturne, but here suggest an atmosphere of stifling summer heat.

Better known in Australia is Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack (1893-1965) who was born in Frankfurt, had fought in World War I and later studied at the Bauhaus, where he was taught by Klee, Kandinsky and others. He had moved to Britain in 1936 because although both his parents were members of the Evangelical Reformed Church, his partly Jewish background exposed him to the ever-harsher anti-Semitic laws introduced from the mid-1930s.

Hirschfeld-Mack was released from detention in March 1942, under the patronage of James Darling, the headmaster of Geelong Grammar School, and became art master at the school until his retirement. Among the works he made at this time is an allegorical watercolour, distantly recalling Blake, in which a Christ-like figure arises from a grave in a battlefield filled with dead soldiers and appears to unify the world in peace.

A little earlier, he had produced the most memorable image of the camp, because it transcends documentation and becomes emblematic of perennial human experience: it’s a simple woodcut that has usually been given the title Desolation, and shows a figure standing in front of the same camp fences that appear so often elsewhere, but looking up at the Southern Cross in the night sky. We recognise the stars intuitively as a symbol of hope, but there is perhaps something more: an allegorical constellation of four stars, representing the four Cardinal Virtues, is a prominent motif at the beginning of Dante’s Purgatorio (Canto I, 23 ff.), so the stars here too may express the promise that suffering will end one day.

Christopher Allen is a member of State Library Council

Dunera: stories of internment

State Library of NSW to May 9, 2025

Dunera: stories of internment

State Library of NSW to May 9, 2025

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout