Poussin’s undying fondness for Narcissus: art review

Poussin had a particular fondness for Narcissus who was punished for his pride by being doomed to fall in love with himself.

The collection of attributes that we call genius – exceptional talent, strength of character and unrelenting determination – can take different forms. We call prodigies those whose genius manifests itself early, as in the cases of Bernini or Mozart; but what allows for this early flowering, in addition to the qualities already mentioned, is a set of unusually favourable circumstances. Frequently, as with Bernini or Mozart, the young artist’s father was already a practitioner, so the child was raised in the art; and at the same time there was a strong demand for the music or sculpture they were producing, so that early promise was at once recognised and encouraged.

It takes a different sort of genius to find your way when you have had no training and when the environment is indifferent or even hostile, as many serious artists find today, when the art world and even our art schools and galleries are dominated by money, fashion and ideological posturing. Nicolas Poussin, however, shows what can be achieved from the most unpromising starting point.

During the 16th century, French culture in general and art in particular had been going through a phase of learning from the more advanced example of Italy, although as I mentioned earlier, the lessons of Mannerist Italy were confused and inconsistent: a succession of talented but eccentric painters worked at the château of Fontainebleau, and helped to foster a school of homegrown Mannerist painters. In the second half of the century, a great deal of art was destroyed by iconoclastic Protestant mobs, so by the time of Poussin’s birth, the country was an artistic backwater and any young painter of talent made his way to Rome as soon as possible.

Poussin was born in a country town in Normandy, to a respectable family of minor nobility, and was most probably sent to school at the Jesuit college in Rouen. He thus had the best education available at the time and was far more literate than almost any artist of his time except for Rubens. His parents probably expected him to pursue the study of law, but he was drawn to art from an early age, when as an adolescent he watched a minor painter executing a commission in the local church.

Later he worked briefly with a more eminent mannerist painter in Paris, but learned more from studying prints of Raphael’s work in the collection of a Parisian connoisseur. Fortunately the Jesuits took art seriously and even encouraged drawing, and it is no doubt through Jesuit connections that the young Poussin met Giambattista Marino, one of the literary stars of his day, when he was visiting Paris. Poussin entertained Marino while he was ill by drawing an early suite of ink and wash illustrations to Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Marino in turn encouraged Poussin to travel to Rome where – after some delays that have puzzled scholars – he finally arrived in 1624, at the age of 30. This was quite old to be a newcomer in the most competitive art market in the world, but Poussin relatively soon made his mark and was taken up by the single most important figure in the artworld of Rome, Cassiano dal Pozzo, scholar, collector and secretary of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, nephew of Pope Urban VIII.

Cassiano soon identified Poussin and Valentin de Boulogne – both French – as the two most promising young men in Rome and set up the pathway for them to build great careers: first a private commission for Cardinal Francesco (Poussin’s Death of Germanicus and Valentin’s Allegory of Rome) in 1627, and then an altarpiece for Saint Peter’s (Poussin’s Saint Erasmus and Valentin’s Saints Processus and Martinian) in 1628. After the successful completion of these tasks, the next step could have been a larger commission, such as the decoration of a whole chapel.

Neither painter was to follow this path, however. Valentin died prematurely in 1632, in circumstances that remain somewhat obscure; he is supposed to have been feverish after spending a night of heavy drinking and smoking with friends, to have thrown himself into the famous fountain which is still in the Via del Babuino, and to have caught a chill which carried him off some days later. No doubt he was already very sick and the chill may have precipitated an attack of pneumonia.

Poussin, however, had not enjoyed the experience of being set up in the kind of contest that the Roman artworld had relished for the past two decades – between Domenichino and Guido Reni, for example, or Domenichino and Lanfranco. The two altarpieces were picked over by artlovers and would-be experts, arguing about the composition in this picture or the colour in that one, in a way that Poussin clearly found very uncomfortable.

He therefore made a radical choice, essentially to abandon the path that had been opened up for him, and to concentrate on painting easel pictures, as he pleased, for a market of connoisseurs and private collectors. This was tantamount to renouncing any hope of a great career in art; but Poussin’s decision paid off and within a decade or two he was possibly the most admired painter in Rome, and certainly one of three, together with Claude Lorrain and Pietro da Cortona, the only one of the group to be a conventional grand-career painter.

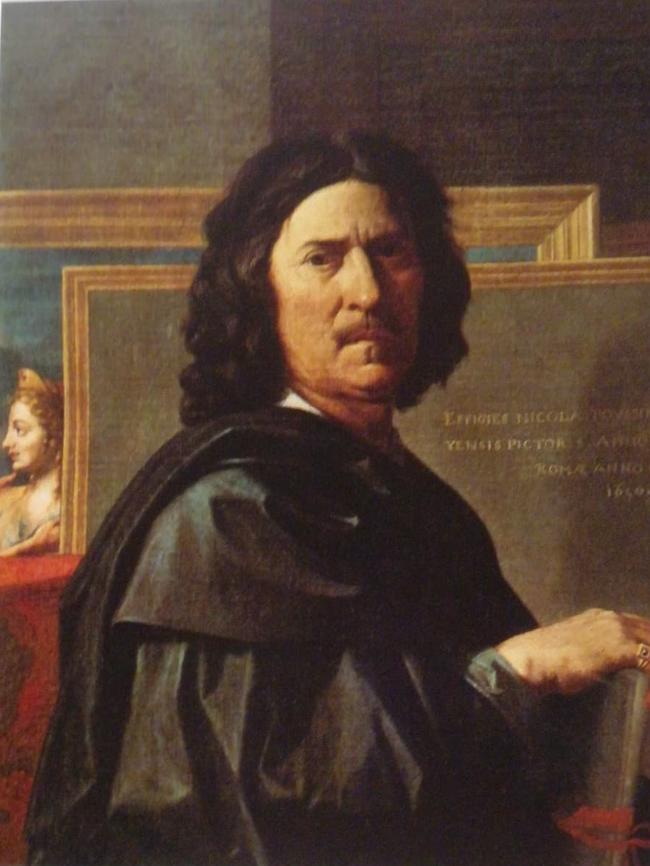

Poussin’s self-portrait, painted at the height of his eminence, hints at his special status in Rome as not only a great artist but as a kind of sage, a painter-philosopher. And it is only in approaching his painting as a series of philosophical meditations through stories and images that one can understand his uniquely original use of mythology, but also his personal approach to subjects from scripture, and particularly the stories of Moses.

One the first things that strikes us about Poussin’s mythologies is how little interest he has in the conventional erotic subjects, particularly the endless loves of Jupiter. He is far more drawn to the particular category of figures who die and are transformed into flowers. One of his earlier paintings, The Empire of Flora (1631) is a collection of these subjects: Hyacinthus, Adonis, Narcissus, Ajax, Clytie, Crocus and Smilax. They are all symbols of love, death and rebirth, in a cycle of life governed by the sun, whose chariot drives through the heavens above.

As I mentioned last week, Poussin was a neo-Stoic like Rubens; but whereas Rubens was interested only in the ethical teachings of Stoicism, Poussin was concerned with its deeper philosophical and cosmological implications. The Stoics had borrowed their cosmology from the pre-Socratic Heraclitus, because they wanted to demonstrate that the order of nature is both rational and necessary, whereas the Epicureans borrowed their cosmology from Democritus, to support their view of the world as ruled by chance.

The world reason or Logos was regularly imagined, literally or figuratively, as the active element of fire, while the elements of earth and water were passive and receptive. What Poussin’s painting demonstrates is the action of the active element in vivifying the passive elements and essentially setting in motion the process of nature itself, with its recurrent cycle of birth and death. Poussin’s concern with cycles is also expressed in the many pictures in which he depicts dancing figures, and which are the special focus of an exhibition that opens today at the National Gallery in London: Poussin and the Dance (until January 2).

Among all these dying and reborn figures, Poussin had a particular fondness for Narcissus, who had also been painted by Caravaggio. The subject is such a superficially familiar one – and since Freud’s adoption of Narcissus to symbolise a psychological condition the word is so commonly used – that we can easily forget both how relatively rare it is in art and how relatively recent it is in mythology.

Most of the tales in Ovid’s Metamorphoses are his distinctive, vivid and yet ironic retellings of much older myths. The story of Narcissus, however, is not an old one; the only other known sources attest to the existence of the tradition in Greece at a slightly earlier date. The name Narcissus appears around seven centuries earlier, in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, as the flower created by Earth to entrap Persephone, but it is not the name of a person.

In the story Ovid tells (the Greek versions vary slightly), Narcissus is a beautiful youth who attracts lovers of both sexes, but who spurns them all in his desire to remain virginal. The aspiration to celibacy in humans is generally regarded as hubristic in the ancient world, and he is punished for his pride by being doomed to fall in love with himself. Catching sight of his reflection in a pool, he is smitten with love and even when he realises the illusion cannot bear to leave. He wastes away and dies, transformed into the narcissus flower, while Echo, a nymph condemned only to be able to repeat the words of others, loving him vainly, gradually petrifies into a rock.

There are several surviving frescoes from the Roman period, but the subject was comparatively rare in modern painting; no one, in fact, seems to have been as interested in it as Poussin. He painted the famous version in the Louvre shortly after setting out on his independent career (1628-30), and a small picture credibly attributed to the same period, and showing Narcissus just at the point of catching sight of himself in the water, was sold by Sotheby’s in New York in 2019.

The Narcissus theme may appeal to some artists because of its homoerotic connotations, but in Poussin’s case I think the meaning is deeper, and that it represents something like the incapacity of the human mind to know itself or capture its own essence, and perhaps the futility of an introverted quest for self-knowledge – this would incidentally be consonant with the emphasis on self-knowledge and reflection on its limits in the French intellectual tradition from Montaigne to Descartes, Pascal and La Rochefoucauld.

Poussin takes the theme of Narcissus much further in the Birth of Bacchus (1657), although he also appears in the unfinished Apollo and Daphne (1664). The infant Bacchus, born from the thigh of Jupiter after his mother had been consumed by divine fire, is brought from heaven to be raised in the watery domain of the nymphs: the mythological symbolism of the Empire of Flora is now deeper, more personal and less obvious.

Scholars have been puzzled about the presence, on the right, of the expiring Narcissus, who has no obvious connection to the story of Dionysus. But this is simply the ultimate point of a meditation on death as a kind of return into the process of becoming that is nature. Here Narcissus dies just as the descent of Dionysus symbolises the inauguration of the natural world; man dies, the god is born.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout