Persian texts take the viewer beyond good and evil

AN outstanding exhibition of books from the 13th to the 18th centuries takes us to an Islamic world that is unimaginably remote from the present.

LITERARY characters, like men, Aristotle wrote in the Poetics, differ in being either good or bad; except that the term he used for virtue, arete, suggests things such as courage, justice and magnanimity, while kakia connotes cowardice, pettiness and baseness.

Nietzsche was the first modern thinker to understand the difference fully, and he made it the basis of a penetrating critique of Christianity.

Even an entirely committed Christian has to admit that his philosophy is paradoxical in the fullest sense of the word, contrary to the doxa, the normal or commonly received wisdom. It is natural to esteem those who are beautiful, gifted, competent, well-balanced, prosperous, beneficent and responsible members of society, and to value them more highly than those who are the opposite of all these things. They possess, by nature, fortune or hard work, the things we all rightly desire. Christianity, however, enjoins us to love also those who fall short in all of these respects, and even those who fail and drop out of the social fabric altogether.

But Nietzsche was concerned with the source of Christian morality as the values of an underdog class; it originated, he believed, in resentment - a central concept in his thought - of those who had wealth, power and other advantages. These people were conceived of as wicked, and thus the Christian could think of himself in contrast as good. The slave, as he put it, can only think of himself as good by positing that the master is bad: thus the slave's affirmation of himself and his values is fundamentally negative in origin, arising out of hatred, envy and anger, not joy, love and the acceptance of life.

This is the meaning of Nietzsche's quest for values "beyond good and evil"; in the Christian view, he believed, morality was founded on the idea of badness, and goodness was defined by abstaining from the wicked pleasures of the master class. In the Greek view, with which he had more sympathy, goodness was primary. The agathoi, those possessing arete, were those who were just and true and high-minded, intelligent and generous, while the kakoi, the base, were unjust, false, self-interested, stupid and mean. It is hard to deny this is both a saner and a more appealing conception of virtue.

Today, of course, there are countless examples of the more poisonous varieties of such morality, lamentably displayed in today's US political circus. But the Nietzschean critique could even more usefully be applied to contemporary Islam. Is there today a better example of the culture of resentment? The Islamic fundamentalist's sense of his own rightness is entirely founded in his belief in the wickedness of the Western other. We are bad, therefore they are good.

But Islam has not always been like this, nor do most Muslims share these extremist views, although, as some of the community's French leaders have now admitted, they have time and again failed to denounce extremism in sufficiently unambiguous terms. In the long run, it is plausible to hope Islamism will fade away with the progress of modernism and economic development, following, if belatedly, the example of the West. The phenomenon of extremism itself is part of the breakdown of the old pattern of belief. Religious fanaticism is a symptom of the decline of belief, and sectarian rage a sign of panic before crumbling certainties.

The figure that Nietzsche chose as the symbol and prophet of his proposed revaluation of values on the basis of affirmation rather than negation was the ancient Persian prophet Zarathustra or Zoroaster, and it is to Persia that we are taken by a truly outstanding exhibition of illuminated books from the 13th to the 18th centuries that comes to the State Library of Victoria from the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford - and to an Islamic world that is unimaginably remote from the absurd and monstrous events of the present day. The title of the show itself, Love and Devotion, speaks of diametrically opposite concerns and aspirations.

It is important to understand the specific historical context of this art. Islamic civilisation itself began when the Arabs conquered large parts of the Byzantine world.

In the subsequent centuries, they enjoyed a golden age in Baghdad and in the south of Spain, producing remarkable architecture and an enduring literary masterpiece, The Thousand and One Nights. In the course of our Middle Ages, they were overrun by the Turks and eventually became part of the Ottoman empire until its breakup after World War I.

In the 7th century AD, the Arabs conquered Persia and imposed Islam in place of the ancient Zoroastrian religion. The Persians, today the Iranians, had ruled an empire that extended to the Mediterranean Sea from the 6th century BC to the conquests of Alexander the Great, and this proximity to the Greeks provoked the great conflicts of the two Persian wars in the early 5th century BC. But the Persians were also related to the Greeks as an Indo-European people and, as we learn from some of the magnificent illuminations to their great historical record, the Shahnama, later considered Alexander the Great - Iskandar - to be the legitimate successor of Darius.

The origins and history of the Persians, whose civilisation was thus far more ancient than that of the Arabs, help to explain both their love of figurative art, generally prohibited by the Arabs, and their much more sophisticated literary tradition. The power of this culture is demonstrated in the rapidity with which it assimilated and civilised the originally barbarian Turkic conquerors who invaded about a thousand years ago and ruled them for most of the second millennium. It is the same pattern we encounter in China, where barbarian Mongol invaders were rapidly assimilated by the superior civilisation of the Chinese and became the Yung dynasty.

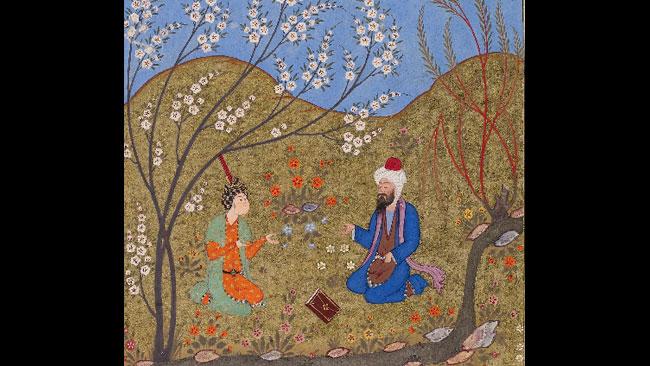

Two things are perhaps equally striking about the illuminated manuscripts in this exhibition. One is the exquisite refinement and supreme artistry of the paintings, and the other is the compelling impression of a love of life and a delight in the phenomena of the natural world, gardens, flowers, animals and other creatures. The love of life is the opposite of nihilism; it is a highly attractive quality in people, which we quite rightly take as a sign of intrinsic goodness. But refinement and care are also profound affirmations of humanity, as precious as carelessness, laziness and mediocrity are contemptible.

Another theme the exhibition suggests is the importance of what we might call secular concerns in art. There is no room for the secular in the mind of a fanatic, and correspondingly a strong secular culture is a bulwark against the claims of zealotry.

Romantic love, in particular, is a force for good, opening our eyes, as it does for the first time at puberty, to the beauty and wonder of the world around us. All those flowery meadows, trees filled with blossoms and cool rivulets are presented as though seen through the enchanted eyes of the lovers who sit by them.

Yet as in the first works of modern Western literature, the poems of the troubadours, the dolce stil novo and the monumental Divine Comedy - and following the connection first established by Plato - earthly love can also lead to spiritual insight, and even to mystical union with the divine. This is a theme frequently pursued in Persian poetry, although anathema to the fundamentalist, for whom sensual delights are only to be anticipated post mortem.

Some romantic tales, such as that of Majnun and Layla, are tragic; others end happily, like the Persian retelling of the story of Joseph and the wife of Potiphar from Genesis. The situation seems to be an archetypal one, familiar in classical literature from the relationship of Hippolytus and Phaedra, and the less well-known misadventure of Bellerophon with the wife of his host in Iliad VI: a young man rejects the advances of a married woman, who then accuses him of rape and has him punished.

The feelings of Potiphar's wife are barely evoked in Genesis, but the Persian story names her Zulaykha and describes her passion as wilder than those of Phaedra and Dido: distraught with love and desire, she has to be held down by her attendants. And while she appears in the Bible merely as a wicked catalyst for what happens next, in the hands of the Persian poets she is a romantic heroine, destined to be redeemed in the end, after many more adventures, and united with the miraculously beautiful and inspired Yusuf in a symbolic conjunction of the human soul with the divine.

The aesthetic of the Persian scribes and illuminators is so refined as to make much even of the beautiful work of the Persian-influenced Mogul artists pale in comparison. The writing, done first, is exquisitely light and precise, yet fluent in a way possible only in the Arabic alphabet employed for the transcription of the Persian language; a friend of mine observed that the flowing and swelling of the calligraphy evokes the romantic and erotic feeling of the poetry itself. The illuminations are extraordinarily rich and jewel-like in colour, combining animation in the handling of figures and natural details with an absence of perspective that gives the images the vivid unreality of a dream.

Ornamental borders are often intricate, adding to the sense of the exceptional concentration and attention that have gone into the making of these precious volumes, but the same care extends to the quality and preparation of the paper, including that of the margins beyond the image and its border - in some cases stencilled with shadows of trees and flowers in a garden.

This literature of sensual delight tinged with pathos and illuminated with spiritual longing was made widely familiar in the West in Edward FitzGerald's translation of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat, and deserves to be better known. It is deplorable that such an admirable civilisation should today be in the hands of bigots who consider all this beauty to be vanity and toy with fantasies of armageddon, and terrible to think of what could befall the country and its people at any moment as a result of the folly of leaders who are so far from representing the best of their nation's tradition.

Love and Devotion: From Persia and Beyond

State Library of Victoria, to July 1