Perfect mix of violence and excitement: Mad Max and co

American mass culture is extremely unsophisticated. But that only partly explains Australia’s disproportionate impact on Hollywood.

A visit to the National Film and Sound Archive and the National Museum of Australia on the same day is to be confronted almost brutally by the difference between good and bad architecture – especially if, as I did, you go directly from the former to the latter. And the basis of that difference is not merely in proportion, symmetry and other formal features, but above all in humanity.

The National Museum is undoubtedly the ugliest example of official architecture in Australia, made even worse by so prominently occupying such a beautiful site. It is a painful example of inept, clumsy and gratuitous form justified by kitsch symbolism with, as I observed on the first time I visited it, all the atmosphere of an airport in a third-world country. Above all, it is an alienating structure, aggressive on the outside and vast yet shapeless on the inside; there is no sense of human proportion or of welcoming visitors into a harmonious and communal environment.

The National Film and Sound Archive, on the other hand, occupies a handsome building that is dignified without being overbearing, grand without losing a sense of human scale and intimacy. The entrance foyer reminds one that a sense of spaciousness depends on proportion, and is lost when the scale is increased to a point where it is out of proportion to our bodies. That is why the cavernous spaces of public buildings designed for mass visitors don’t feel spacious so much as dehumanised.

Corridors leading from the foyer are modestly proportioned too, so that you feel drawn to walk down them. And beyond is a courtyard surrounded by cloisters; the courtyard is filled with a garden and a pond, and aromatic herbs like rosemary and lavender grow in clumps. It is an inviting space, even on a cold day, where you feel the presence of living nature and sense the personal care that has set out these plants and tended them.

The building, completed in 1930, was originally intended to be a National Museum of Australian Zoology, but in 1928 the institution was renamed the Australian Institute of Anatomy. It flourished until its collections were moved, ironically, to the newly established (1980) National Museum of Australia. In 1984 the old Institute became the home of the National Film and Sound Archive, which had previously been a department of the National Library.

One reminder of the building’s original purpose is in the theatrette where today samples of historic film are shown. It is small but above all the rake of the seating is quite steep, recalling the anatomy theatres of past centuries – the most famous being the still extant anatomical theatre of Padua – in which students gazed down from balconies to watch the cadaver being dissected and commented on by the professor and most likely a technical assistant.

Cinema, of course, doesn’t dissect bodies or look into their inner workings, but exists ostensibly at least on the level of surface and illusion, even if the ultimate aim of the illusion, as in theatre, from which it evolved, is to reveal some kind of truth or reality. According to Gorgias as quoted by Plutarch, theatre is a kind of deception in which he who deceives is more honest than he who does not, and he who is deceived is wiser than he who is not.

But although cinema grew out of theatre, its means of deception are far more powerful, and this is the fundamental difference between the two forms. In theatre we are asked to suspend disbelief, and our engagement is altogether more active. We can see this in the very way that we sit as an audience. In a theatre we sit up straight or even lean forward on the edge of our seat, intent on the spectacle that demands our intellectual and emotional participation; in cinema we lounge back, passively, as the technology does all the work for us.

This is particularly true of Hollywood films and especially the recent phenomenon of schlock blockbusters based on comic book characters, built almost entirely on special effects, and designed to distract the mass audiences from the crises that surround them, reassuring them that things are much simpler than they really are, that all our problems can be reduced to battles between goodies and baddies and solved with guns and very large explosions. There is no other way to experience these movies than in a comatose state; it is not so much suspension of disbelief as of all mental activity.

This exhibition is devoted to the impact that Australians have had in Hollywood in the last few decades, which seems to have been disproportionate, given the relative size of our film industries. Of course we share the advantage of the British and other English-speaking peoples in having the same language, even if American audiences are not very good with other accents, and many of our films have been dubbed into American accents to be palatable, or perhaps intelligible to mass audiences.

There are probably other factors, however, in accounting for our relative success in Hollywood. Apart from a number of remarkable actors who have established themselves as international stars, it may also be that something about the outlook of our films is subtly different without feeling entirely foreign. American mass culture is extremely unsophisticated: audiences love violence, crude and obvious excitement like car chases, guns and shooting; but at the same time they are prudish, moralistic, sentimental and they expect kitsch happy endings.

George Miller’s Mad Max – the original film came out in 1979 – is therefore an interesting case to start with. It has all the familiar ingredients of violence and excitement, but the dystopian scenario allows these elements to be taken to a hyperbolic level at which they become almost playful rather than literally real. And at the same time the social and moral collapse of the film’s imaginary world is so complete and pervasive that it cannot be neatly resolved, as in so many American mass market films, but finding and eliminating an individual who is the supposed source of the corruption.

Baz Luhrmann’s Strictly Ballroom (1992) is set in the kitsch world of display ballroom dancing, but one of its most important themes is of the triumph of authenticity – rooted in the still living culture of Fran’s Spanish migrant family – over the showy but tired routines of the ballroom dancing competitions. A turning point in the film is the scene in which Fran’s father shows Scott how a paso doble should really be danced; not merely with a sequence of steps but with ruthless intensity and psychological focus.

It is with this dance that Scott and Fran finally triumph in an ending that is a masterpiece of suspense, comedy and genuine feeling. It is supremely sentimental, but the sentimentality is, like the violence in Mad Max, taken to such an extravagant level that it too ceases to be literal and is turned into a kind of fairytale.

Strange as it may seem, sentiment raised to this extreme pitch transcends kitsch to become an allegory about the confluence of love, courage and integrity; and the theatrical curtains that close over the dancing crowd at the end remind us that the film has presented us with an artificial, imaginary and even visionary experience of these ideas, not a set of banal social messages.

I remember seeing Stephan Elliott’s Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) in Paris soon after it was released and, especially in that setting, it seemed somehow quintessentially Australian and almost impossible to imagine as an American picture. The subject-matter – three drag queens taking their show on the road in the outback – was unconventional to say the least, although drag queens have a long history in Australia and drag shows were actually in decline by the time the film was made; the famous Les Girls cabaret in Kings Cross closed in the same year.

But what perhaps made this film feel particularly Australian was its combination of uninhibited pleasure in camp, even in the most incongruous circumstances, with more serious personal themes, all the while rigorously abstaining from moralising: thus no apology was made for the sexuality or behaviour of the main characters, but nor was there any heavy-handed social commentary. Instead the formula was over-the-top fun shot through with pathos.

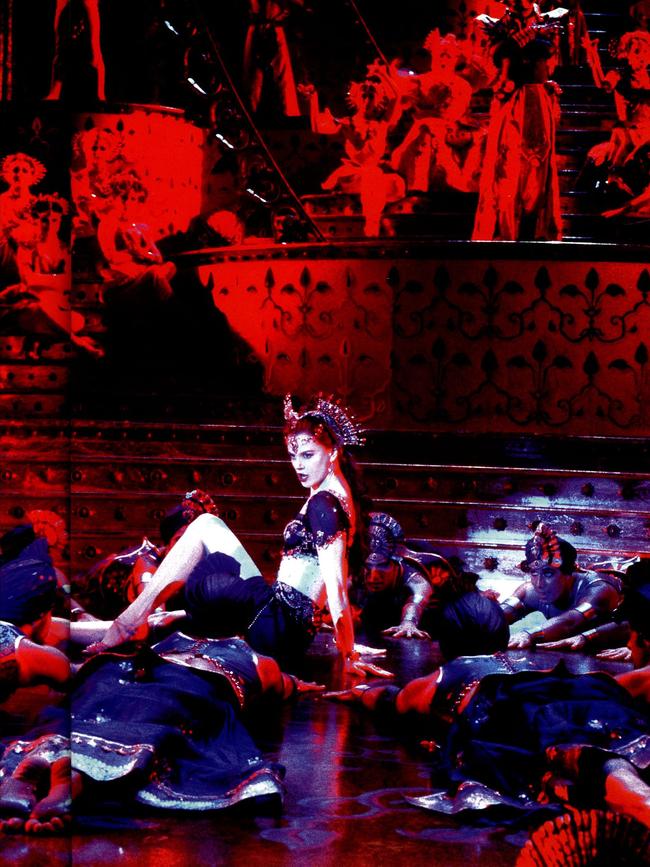

These and other films are evoked in the exhibition through a variety of displays, from wall panels and of course short clips to set models, costumes and props. Thus there are several props from the most recent Mad Max film, and gowns from P.J. Hogan’s Muriel’s Wedding (1994) and Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001).

There are also set models and other displays like a portable make-up case from the set of the last Mad Max. Most interesting, of course, are those displays that give one a glimpse into the production of cinematic illusion.

One of these is behind-the-scenes documentary footage of the preparation for the cancan scene in Moulin Rouge. The scale and ambition of the production are impressive: hundreds of performers are seen now in rehearsal dress and now in full costume; in one sequence all the actors are being urged to join in a collective percussion effect made of stamping feet, clapping hands and glasses banged on to tables. You can feel that this is not only in order to produce an impressive noise, but just as much about raising the energy of the cast and uniting them all in a single paroxysm of dramatic intensity.

The process thus, of course, begins with the performers, and with a big cast and a scene involving so many extras, the collective effect is critical. But then there is the cinematography: the same scene can be shot in different ways, from different heights and angles and points of view. Detailed, hand-drawn storyboards show the planning of successive shots and the alternation between points of view or long shots and close-ups. Cinema can control the viewer’s gaze in a way unimaginable in theatre, which is also why the viewing experience is so much more passive.

But after all the planning, the role of the editor in putting together what the camera has actually captured is crucial, which is why so many directors work so closely with an editor with whom they share an understanding and a vision.

Martin Scorsese has made almost all of his films with Thelma Schoonmaker, and George Miller’s are edited by his wife Margaret Sixel. And perhaps the most fascinating thing I learnt from this exhibition was that Jill Bilcock, the editor of Strictly Ballroom, in the final and climactic scene, had to extend the length of a sequence whose raw footage was too short. By cutting, re-using different shots, and extending the audience’s clapping as soundtrack, she wove together a bewitching and seamless cinematic illusion.

Australians and Hollywood: A Tale of craft, talent and ambition

National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra, currently showing