Part Two, European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This tiny Virgin and Child by Dieric Bouts is among the exquisite paintings on show in Brisbane, reviewed here in our second instalment on the works from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Last week we discussed several of the more important paintings in this exhibition in some depth; this week we will look at paintings from particular regions and in various genres, and next week, in a third instalment, we will discuss the 19th century works that are hung in the final section. And it would be appropriate to begin with the Flemish painters, who sometimes get overlooked when we are following the mainstream of modern art, with its inevitable focus on Italy.

The current of history is not homogeneous or synchronised even across the regions of Europe, let alone the world. The 15th century in Italy was the beginning of what we call the Renaissance, while the same period in the north is generally considered the last phase of the Middle Ages, a culture memorably characterised by Johan Huizinga in a book published just over a century ago, as The Autumn of the Middle Ages (Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen; 1919 in Dutch, with English translation in 1924).

The centre of this late medieval culture – albeit linked by commercial exchange to the Italian centres of Florence and Venice, where the renaissance spirit arrived half a century later – was Flanders. A century later, with the Reformation, the northern part of the Netherlands would break away to become Protestant Holland, while the remaining section of Catholic Flanders would eventually become modern Belgium. In the 15th century, the Netherlands were united, but not independent, since they were part of the sovereign Duchy of Burgundy until the end of the century when they passed to the throne of Spain.

The Netherlands was, with Venice, the most prosperous part of Europe at the time. Burgundian-Netherlandish culture was extremely refined, intensely preoccupied with religious matters, with sin and salvation, but almost equally fascinated by the details of the natural and man-made world around it, from organic forms in landscapes or hair, eyes and the complexion of skin in a portrait, to furniture, metalwork and expensive, imported oriental carpets. In contrast, the artists of Florence were far less interested in surface naturalism and more concerned with the abstract understanding of volume and space.

One of the most touching expressions of Netherlandish painting here is the tiny Virgin and Child by Dieric Bouts (c. 1455-60). The composition is based, as the catalogue entry points out, on the very common Byzantine type known as the Glykophilousa – literally, sweetly kissing – in which the Virgin holds the Christ Child to her cheek, their lips nearly touching in a kiss. Byzantine painters took great trouble to convey, even in their deliberately formalised style, the sweetness of the Mother’s expression. The same is true here, but it is the sheer naturalism of the young woman and the little child, with their soft, pale northern complexions, that is particularly poignant.

Naturalism as a means of evoking empathy is also evident in other paintings, such Petrus Christus’ Lamentation (c. 1450), in which the inert body of the dead Christ is being laid out on the sheet in which he will be buried, while the Virgin Mary, in the centre, is supported by St John, and Mary Magdalene, identified by her jar of ointment, is on the left. The skull of Adam, mentioned last week, appears again at the foot of the cross. The sheet is held by Joseph of Arimathea on the left, and Nicodemus on the right; the latter appears to be a portrait of the donor rather than a generalised face like the others; his expression is at once tender and tentative, as though he feels a little out of his depth playing a part in such a solemn and august ceremony.

Donor portraits are very common in the Netherlandish art of the time, as in Italian art as well, not only recognising the benefaction, but setting the donor in a position of adoration or in this case actual participation in the holy scene forever.

Another such portrait, although we may realise it at first sight, is the striking head of a man by Hugo van der Goes (1475). The sitter is minutely observed and intensely present, even though we no longer know his identity. This appears to be an independent portrait, but the hands held together in prayer suggest that it was once the left panel of a triptych.

Over a century later, there is a fine portrait by a very youthful Hans Holbein the Younger, this time of a known individual, Benedikt von Hertenstein. The painting was made in 1517, and we know the age of the sitter from the inscription, which reads, in German, “I had this from when I was 22”, and then adds in Latin, “H.H. painted”. Holbein was decorating the house of Benedikt’s father in Lucerne at the time and he must have executed a portrait drawing of the young man on paper, later mounting it on a panel and painting over it in oil. If the frieze above the youth’s head looks familiar, it is because the decoration of the house included copies of Mantegna’s Triumphs of Caesar, originally painted in 1484-92 for the Ducal palace in Mantua.

In contrast to such a complex picture, including costume, inscription and significant background details, Velazquez’s portrait of a man, which is thought to be a self-portrait (c. 1635) is informal and was listed as unfinished in the artist’s inventory. In fact, especially if it is a self-portrait, it is more like a portrait sketch – probably a study for a self-portrait included as a kind of signature, like many renaissance artists before him – on the right of his Surrender at Breda. As it stands, the picture is not only a vivid portrait, but a fascinating lesson in how paintings were made: for example, because the artist works from dark up to light, the lit parts of the face are far more thickly painted, while the shadows are much thinner, little more than glazed darker over the initial underpainting of the canvas.

Another fine self-portrait from the mid-17th century (c. 1647) is very different and more elaborate both in composition and allegorical meaning. Salvator Rosa was a Neapolitan mainly known for his wild landscapes, anticipating the sensibility of romanticism, as well as for pictures with philosophical themes and messages. In this painting, made for an intellectual friend, as the writing on the crumpled letter on the lower left tells us, he shows himself carefully inscribing a Greek phrase on a skull with a quill pen. The words can be translated roughly as “behold, where you too must one day come”. The message is a memento mori, but the skull rests, significantly, on a volume of the Stoic philosopher Seneca: for the sage learns by the practice of contemplation to envisage the inevitability of death without terror, thus explaining the still and serene mood of the painting.

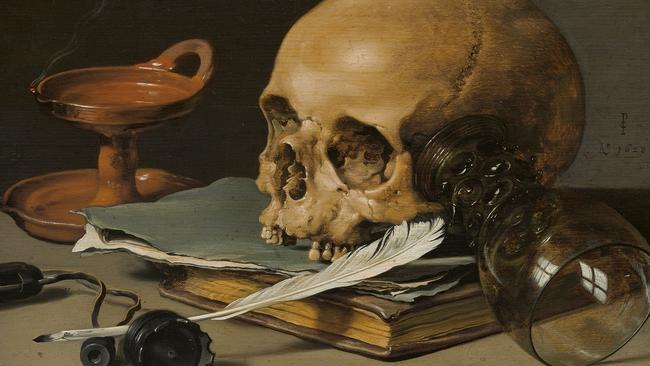

Another memento mori appears in the form of a still life by one of the finest exponents of the genre, Pieter Claesz, Still life with a skull and a writing quill (1628). Once again a skull is set on a book, but here the meaning is rather different, suggesting that the inevitability of death renders even the efforts of scholarship and learning futile. Although the skull must belong to someone who died long before, details like the ink on the quill and especially the still smoking oil lamp imply that death has only just come.

Incidentally, the toothless state of the skull may represent the effects of sugar, which had first been brought to Mediterranean islands such as Cyprus and Crete by the Crusaders, and by now was being cultivated on a much greater scale in the new world.

The greatest still-life artist of the following century was Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin; he was also known for small subject pictures, mostly with children and including still-life motifs, such as Soap bubbles (1733-34). As in his paintings of a spinning top or a house of cards, the artist brings an extraordinary quality of attention and stillness to a subject that is in its very nature as ephemeral as one can imagine.

And again as in these other paintings, it is the quality of attention in the main figure that invites us to contemplate the momentary phenomenon of the bubble, painted with exquisite economy and delicacy, and yet still including subtle reflections of the surrounding motifs.

There are several fine landscapes from the 17th century, above all a beautiful sunrise by Claude Lorrain, who evokes simultaneously the warmth of the morning sky and the cool of night that still lingers in the foreground shadows, and who creates a kind of counterpoint between the optical attraction of the eye to the brightness and colour on the left, and the narrative content of the composition, as shepherds drive their herds and flocks from left to right, crossing the river to their morning pastures.

In contrast to Claude’s conception of landscape, which is universal although drawn from the countryside around Rome, Dutch landscape of the same period tends to represent specific places in the Dutch Republic, and thus has a range of local and patriotic overtones that are absent from the classical genre. Jacob van Ruisdael’s Grainfields (mid 1660s), for example, is unmistakably Dutch in its low horizon and powerful cloudscape, even without the distinctive touch of a windmill.

Woodland road by Ruisdael’s pupil Hobbema (c. 1670) has the familiar low horizon and cloudscape, but combined with more dominant trees, perhaps learnt from his master, and his own distinctive love of roads leading straight into the pictorial space. Human presence is dealt with in a more anecdotal way, with figures walking both towards us and away on the road, others in the distance on the left, and a woman standing in the doorway of her house on the right.

Antoine Watteau is considered a French artist, although his origins were Flemish, and it was from the north that he brought his own feeling for landscape. But his landscapes are the scene for whimsical and poetic scenes, often drawn from the world of commedia dell’arte performers and their French imitators. In Mezzetin (1718-20), a young man in the costume of this character from the commedia sits in an overgrown garden singing and playing his guitar.

The picture is also presumably a portrait, since the Met owns a red and black chalk study of the head, clearly made from life, and thus Watteau introduces a characteristic note of ambiguity: is the actor merely performing the role of a melancholy lover singing of the girl he pines for, or is the actor the lovelorn subject?

Love is certainly the theme, if we could not guess it for ourselves, for a statue of Venus stands in the garden behind the musician; but alas, the goddess is turning her back on him and his lamentations will be ignored.

European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, until October 17.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout