Part Three: Glimpses of a modern world

The riches from the Met speak in various ways of the changing world from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries.

The last section of this rich exhibition is somewhat more patchy and less coherent than the parts discussed over the last two weeks, and is oddly accompanied by the label “revolution and art for the people”, neither of which is particularly relevant to the works actually selected. These works do, however, speak in various ways of the changing world from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries.

One of the more intriguing pictures at the beginning of this period is a view of Venice, the first city to be itself a subject for painters; Rome was a centre for painters from the renaissance onwards but it was the ruins of antiquity, rather than the modern city, that attracted them. Venice on the other had begun to be painted in the 15th century and is the background, in particular, to the large religious subjects of Gentile Bellini.

By the 18th century, travellers on the Grand Tour would purchase paintings of the ruins of antiquity when in Rome, but in Venice would acquire views of the most picturesque of cities, with canals instead of streets and gondolas instead of carriages. And one of the most fascinating things about these views, as we see in Francesco Guardi’s early Venice from the Bacino di San Marco (c. 1765-75), is that so little has changed in a period corresponding to the whole history of modern Australia.

From the left, after the little bridge, we can see the Mint (Zecca), to which is attached Sansovino’s Biblioteca di San Marco, while behind rises the famous campanile which was built in the Middle Ages, collapsed in 1902, but then rebuilt exactly as before and completed in 1912. Then there is the Piazzetta, running in front of the pink mass of the Ducal Palace and the Basilica of San Marco which can be seen behind. To the right of the palace is the famous prison known as I Piombi; among its well-known inmates was Silvio Pellico in 1821, who later described the experience in Le Miei prigioni (1832).

Many smaller buildings of interest can be recognised to the right, but the change that may strike modern visitors to Venice most of all is the relative position of the two columns bearing the statues of the Lion of Saint Mark and Saint Theodore with his crocodile. Today they are both in line with the Library, but in Guardi’s painting one appears much closer to the water’s edge. The other conspicuous change is that, a generation or so after this painting was made, Napoleon ordered the creation of the Giardini Reali just over the bridge on the left.

Of course, the sailing ships, gondolas and other vessels that crowd the foreground and are dotted across the water are also long gone, although many of them would still have been there when Turner painted his view of the Grand Canal around 1835. What Turner would presumably not have seen, however, is the magnificent state gallery, the Bucintoro, moored outside the Ducal Palace, because by the time he arrived Napoleon had long abolished the millennial republic, and Venice had become an Austrian possession.

Venice, from the porch of Madonna della Salute was based on a sketch made on Turner’s first visit to the city in 1819, but painted following his second visit in 1833. The mood of the city seems to have changed considerably; although the water is full of merchant vessels and gondolas, this no longer feels like a capital with an ancient lineage, but a city emasculated and in the epilogue of its own history.

The title is not strictly accurate, as the Salute is on the right of the composition, which appears to be have been based on a drawing made from a boat in the middle of the Canal; the campanile from Guardi’s painting is now on the left and in the distance, at the entrance to the Grand Canal, we can see the customs house, the Dogana, on the right. And one notable thing, considering Turner’s fascination with the interplay of light and water and the dissolution of solid forms, is the minute attention he pays to the correct drawing of architectural features, particularly in the facade of the Salute.

Although Venice feels timeless, this picture was only painted a few years before the revolt of 1848, which was part of a wave of uprisings and revolutions through many European capitals, including Paris, where riots ended the July Monarchy and led to the rise of Napoleon III. So we are closer than we might think to the more overtly modern world, only a generation after Turner’s painting, evoked by such painters as Manet, Courbet and Daumier.

Of these, one of the most interesting is Gustave Courbet’s The Young Bather (1866). On the face of it this is an example of the modern subgenre of the bather, sometimes male but more commonly female, which is one of the opportunities to paint the figure after the decline of history painting. The most important source for the bather figure is the mythological subject of the Bath of Diana, and so female bathers are at first implicitly nymphs, although they evolve considerably in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries.

It is the vestigial sense that a bathing girl is a nymph that makes Courbet’s bather particularly poignant, for she is very far from that world of ideal forms. She is a tall, rather awkward girl, not frolicking gracefully in a stream but dipping her toe gingerly into the icy water. What is even more interesting although it may not be immediately apparent to the modern viewer, is that her figure is neither ideal nor even natural, but unmistakably deformed by the wearing of corsets; she is thus not a country girl either, but a shop assistant or prostitute from the city acting as the artist’s model.

At the same time, the deformity of her rib cage, in alluding to her habitual dress, achieves the same effect as retaining an item of costume, as in Manet’s Olympia or many later paintings, including those of Klimt and Schiele: bits of clothing, ribbons, shoes and other motifs serve to remind us that the figure is, in Sir Kenneth Clark’s famous distinction, naked not nude. We do not wonder where a bathing nymph has left her clothes, but here we find ourselves looking to see if the girl’s city dress and petticoat are neatly folded somewhere in the background.

It was of course the new railways that allowed city people like this to escape to the country in their free time; the scene here may well be the Forest of Fontainebleau, which today can be reached in 40 minutes from the Gare de Lyon. The comfort of train travel has always varied, however, according to the class one travels in, but this was even truer in the days of Third Class, the subject of a famous painting by Honoré Daumier: Daumier’s experience as a cartoonist is evident in The Third-class carriage (c. 1862-65), based on an earlier lithograph.

The figures in the background include four men in top hats, but whose gaunt features hint at their reduced circumstances; the young woman with her baby and the old woman, perhaps her widowed mother, evoke the eternal cycles of human life, now playing out in the new industrialising world of Second Empire France: the young woman is absorbed in nurturing new life, while the old one gazes distantly into space, stoically enduring the latter part of a hard existence.

Degas represents another part of the modern French world in Dancers, Pink and Green (c. 1890), an oil painting which curiously emulates the effect of pastel, at first sight remote from Daumier’s impecunious third-class passengers. Reproductions of his ballet pictures hang, as I have observed before, in every suburban ballet school, testimony to how superficially people look at pictures. Another paper even had a couple of pretty ballet dancers pose with this painting, assuming elegant attitudes on either side of it.

Degas does sometimes show his dancers transformed in moments of beauty on stage, but his point is that this is a miraculous metamorphosis wrought by art; the girls themselves are from poor working-class backgrounds, and are not inherently distinguished by education, grace or character. When not submitting themselves to the rules of choreography, they are usually sitting around, scratching themselves or, as here, fiddling with costumes and adjusting shoulder straps.

Painting too is a magic that can transform banality into beauty and the harmonious rhythm of the girls’ backs is ultimately inspired by Raphael’s engraving of The Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1511). But the silhouette of a man in a top hat, just visible past a stage flat, reminds us the other reality of these girls as the erotic playthings of wealthy patrons.

There are still too many pictures to do them all justice, including a Goya portrait, a fine Manet chosen to emphasise his debt to the Spanish and especially to Velazquez and a poetic late landscape by Corot, in a cool northern palette. One thing worth noticing in this picture is the way that the artist has changed his mind and opened up a hole in the mass of trees to reveal the sky and to allow us to have a clearer sense of the row of houses along the bank of the river; but he has done this rather quickly and carelessly, so that the paint is blended on one side but forms an obvious and unresolved edge on the other.

The Vincent van Gogh picture selected for the exhibition is a surprisingly minor work, a flowering orchard painted in early spring 1888 shortly after his arrival in Arles at the end of winter; it represents the beginning of his transition from the impressionist style he had learned in Paris over the previous year and a half and the start of the development of the mature style which he then practised for two years until his suicide in mid-1890.

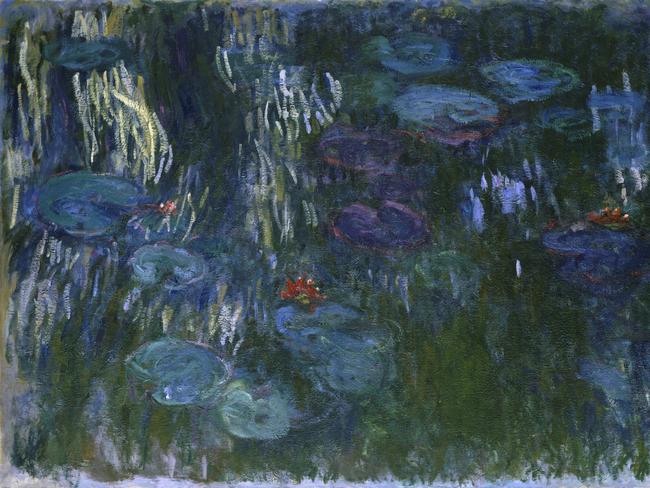

There are two Cézanne paintings, both good but relatively minor works: one a still life and the other a view of a Gardanne, a town entirely composed of the angular little forms which served him as keynotes in his more important landscapes and later inspired the Cubists. Monet is represented by a childhood portrait of his son Jean riding on his hobby horse (1872), and by a very late painting of his lily pond at Giverny (1916-19): but this subject which begun as a celebration of light and colour and had evolved into the vehicle for almost mystical reflections on the very nature of being, is here overshadowed and darkened by the tragedy of war and the death, in 1914, of the child on the hobby-horse.

European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, until October 17.