Oh no, not you again - the Archibald, Sulman and Wynne prizes

THIS time of year sees the same familiar picture of disparate mediocrity but some contenders still manage to stand out from the crowd.

ACCORDING to Friedrich Nietzsche, who was quoted here a couple of weeks ago, the ultimate test of the affirmation of life is a willingness to embrace the eternal recurrence of everything that has happened to us: to relive all that one has experienced again and again, always in a spirit of joyous acceptance.

Nietzsche himself thought of this as a grave challenge. But he didn't have to attend and, worse, review the Archibald Prize as it comes around relentlessly year after year.

The faint dread of anticipation begins weeks ahead as the hype builds, and then there is the unveiling of the finalists, which are individually different but together form the same familiar picture of disparate mediocrity. The deja vu reaches its climax at the announcement of the winner. And then there's the depressing experience of returning to watch visitors trying to see why these pictures are meant to be good.

Meanwhile, macrocephaly remains endemic, although perhaps slightly in retreat; sitters should consider that the vulgarity of the scale reflects on them as well as on the artist. Related to the question of scale is the problem of reliance on photography, which in spite of feeble precautions on the part of the gallery, continues to be a rampant abuse and the principal cause of death in so many still-born paintings.

But there is another factor in the Archibald syndrome: it is the concentration on the head and face alone, as though the identity of the sitter were reducible to his features. This is the assumption of the police mugshot, but if you've ever seen a mugshot of someone you know, you will have noticed that the person seems almost completely absent, the humanity and character stripped away in the determination to capture the external and objective shape of the features.

Human beings are gregarious, conformist and suggestible. Why else do people spontaneously adopt inarticulate idioms picked up from the mass media? And why do they do more dangerous things, such as adopting modish ideas, populist prejudices and simplistic political ideologies? Why, in fact, do individuals want to give up their independence and become part of a mass? Perhaps it is too much of an effort and a responsibility to stand on your own feet and take the trouble to find out what you really believe.

In any case, something like this is what helps to explain the acceptance of a gigantic mugshot as an acceptable format for a portrait. It is the tacit assimilation of a massified consumer environment in which the universal experience of the portrait is the security identification photo on your driver's licence or passport. In this regard, it is interesting that a couple of pictures even have the face cropped, exacerbating the mugshot effect and evoking the evolving technology of biometric scanning.

It is of course an impoverished conception of portraiture to think of it simply as a face blown up to colossal scale. Reflect for a moment on what makes you recognise a friend, what gives you a sense of their character. It isn't simply their facial features; it's their whole bearing: the way they hold their head, the way they stand and what they do with their arms and legs. Mugshots, as just mentioned, can look oddly unrecognisable, but how often do we feel this also about passport photos? On the other hand we can usually recognise a friend even from behind, and in the distance, from their stance and their gait.

Likeness - in the deepest sense of the word - doesn't consist in the photographic accuracy with which we note every mole, facial hair or age blemish, but in the overall sense of a movement and life within the person, and this, as we know, is compatible with a considerable degree of simplification, stylisation and even abstraction. But what most helps in capturing that impression of a living human being is to include at least the head and shoulders of the figure, but preferably the arms and hands as well.

The Archibald finalists were dealt with in detail in my preview of the exhibition a couple of weeks ago, and there is little more to add on a second viewing apart from the fact that the prize was awarded to Tim Storrier for an eccentric allegorical self-portrait, loosely based on a Hieronymus Bosch painting of a wandering beggar and crossed with T.S. Eliot's memorable image of the hollow man. Storrier's alter ego is dressed as a colonial explorer, searching through a wasteland and encumbered with paraphernalia that recall his themes as well as the tools of his trade. Crowded with myriad cleverly painted details but revealing vacancy at the core, the picture appears to be a disarmingly frank act of aesthetic introspection.

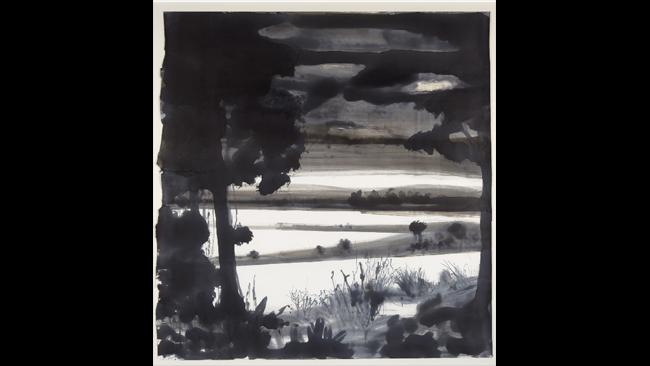

The Wynne Prize for landscape is this year rather better than usual, with a number of good and reasonable pictures. One of the most engaging is a large work by Susan White that was deservedly awarded the Trustees' Watercolour Prize. It is a view of a favourite place, painted from memory in black, grey and brown wash - broadly using the same sort of monochrome media that Claude Lorrain and other landscape artists from the 16th to the 19th century employed for outdoor sketching and similarly framing the view in dark silhouetted trees that emphasise the depth of space, in this case perhaps as a metaphor for the depth of remembered associations.

Another fine watercolour, by Alicia Mozqueira, is in contrast much smaller and much denser, recalling the richly decorative miniature painting of the oriental tradition discussed here a couple of weeks ago.

Mozqueira's picture too is based on memory, and in her case it is as though observation and experience have been concentrated and compacted as they are recalled in imagination.

Among oil paintings, Philip Wolfhagen and the younger Guy Maestri hang side by side and each is deserving of attention. Wolfhagen's painting is essentially a cloud study, and would probably be more effective on a rather smaller scale, but it is subtle and simple, attentive, as he notes in a mercifully brief and relevant label, to the minimal variations of tone and temperature that evoke the effect of distance. Maestri's painting is also rather large for the level of its resolution: it is effectively a sketch, but it shows a real feeling for the humble natural motif he is looking at. He needs, however, to beware of the temptation to think that this is as close to the truth as he can get; it is possible to pursue a more refined level of articulacy without losing touch with spontaneity or authenticity.

Alexander McKenzie represents the opposite danger: a formulaic slickness that verges on kitsch partly because - as the label that accompanies the work suggests - he thinks too much and too superficially, and doesn't spend enough time looking at the world of nature. The picture is full of conceits, while the sky and sea and other elements are painted as inert formulas.

Nicholas Harding has an impressive pandanus growing on the seashore: a substantial picture in which he manages both to capture the effect of the light on the rocks and to evoke the vitality of the plant itself. Kevin Connor's view of the harbour, Moonlight Bay, was one of the two paintings between which the judges made their final choice, a big lyrical canvas of which the artist rightly says that it should be looked at in silence.

The Wynne Prize was awarded to Imants Tillers for a work based on Fred Williams's Free copy of Von Guerard's waterfall at Strath Creek, 1862 (1970), today in the NGA; the original hangs in the collection of the Art Gallery of NSW. Tillers has made versions of Von Guerard, one of the most important of Australia's colonial painters, for many years; but this picture is at one further remove, an interpretation of an interpretation.

The result, immediately apparent, is a certain flat and insubstantial quality to the picture surface, areas that seem cut out like silhouettes or stencils rather than conceived as objects to be painted or even as painted marks to be imitated. The effect is in one sense comparable to Chinese whispers: Tillers is working from Williams's sensitive but still considerably simplified copy, and it is not possible, on the basis of the information this version contains, to reconstruct the original Von Guerard.

Hence the mute, flat passages where a Williams gestural mark was only a loose approximation of the underlying image. And yet this somewhat disembodied effect does not detract from the purpose of the image, for Tillers is more concerned with a meditation on the movement of water than on the precise definition of rocky forms; his subject is flux and movement, illusion and perception, as the Hindi text inscribed on the picture's surface makes clear.

If all these pictures - and others by Robert Malherbe, Robert Ewing and Noel McKenna - are worth pausing for, there are a couple that stand out in a different way. Camille Hannah's Austramythicus-paternus deserves special mention for the strident vacuity of the painting itself, compounded by an unusually pretentious title and an equally smug label, in which Hannah assures us that the picture is about "a mythology fermented by dreams born long ago. . ." Michael Lindeman's work is also distastefully smug, and his one idea is wearing very thin.

The Sulman Prize is mostly too substandard to discuss in any detail, filled with banal photographic realism and self-conscious yet humourless quirkiness. Two pictures catch one's attention - a suggestive interior in minimal monochrome by Janet Haslett and a deliberately odd figure subject by Laura Courtney of a woman doubled up behind a closed door in an intimate telephone conversation, recalling the time, which now already seems so remote, when a call had to be taken wherever the telephone was plugged in, even when surrounded by indiscreet ears.

The Sulman was rightly awarded, in an extremely weak field, to a brooding interior by Nigel Milsom. The image has a post-photographic quality, and plays with lines of sight and perspective effects as well as ambiguities between illusionistic space and flat patterns cut out of the picture plane. It succeeds in evoking a slightly film noir ambience, with recollections of the urban interiors of Edward Hopper, and it does have, in keeping with the terms of the prize, a focus on a human subject.

Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012

Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, to June 3