No Turning Back: a white girl’s life on an Aboriginal mission

As the daughter of white missionaries, I lived among Aboriginal people until age twelve. The culture shock was extreme.

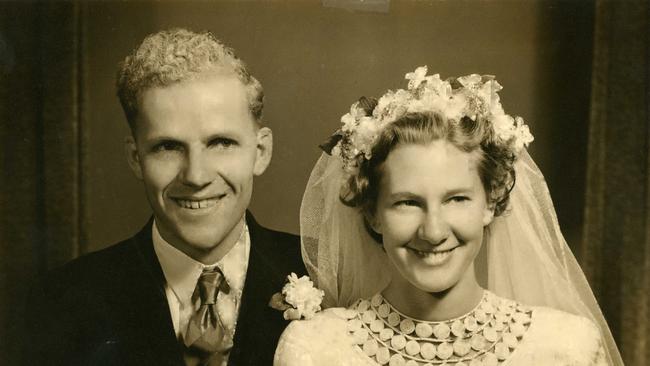

My parents, Pearl and Bruce Smoker, had not planned to become missionaries. My father was the son of a farmer originally from Pingelly, a small wheatbelt town 158km southeast of Perth, Western Australia; my mother was the daughter of the local Police Constable in Mount Barker, a small town just under 360km south of Perth.

But they were committed Christians, and had received their call, and so in late January 1952 they packed as much as they could carry on a plane, and flew to the remote settlement of Fitzroy Crossing on Bunaba country to assume the role of assisting the management of the Aboriginal Mission. They were newly married, and just 23 years old.

It took some time for them to grow accustomed to the climate – the heat was almost unbearable – and the sprawling disjointed settlement. The Mission was situated on a high ridge to avoid flooding during the wet season. There were just three Nissen huts and a partially built rustic cottage. One of the Nissen huts became their home, the other the Mission store and the third, a partially finished hut, became the camp kitchen. There were some temporary small huts scattered around for Aboriginal people. These consisted of a wooden frame, hessian for walls, and a tin roof made from unused Nissen hut iron which offered little protection from the elements.

My parents’ Nissen hut home was painted black, so the already hot days of 44C rose to 50C plus inside, it was eventually repainted silver making it a little cooler, but they still lived most of the time outside of the hut due to the heat.

There were 26 Aboriginal adults living on the Mission when my parents arrived. They were mostly elderly, disabled, or unwell, and there were a few young single mothers. My parents were employed to distribute government rations to these people. Weekly food parcels consisted of flour, sugar, tea, powdered milk, beans, and sometimes tinned meat and tobacco.

Out of necessity the maintenance and building program took up much of my father’s time in their first few years on the Mission when he was not distributing rations. He worked alongside the few able-bodied men in the mornings until lunch and after 3pm in the afternoons, and everyone had a rest during the midday heat.

With help from the men, together they were able to finish the meat house … they also fenced a yard for a small goat herd and erected more fencing to protect the vegetable garden. A camp kitchen and dining area with tables and bench seats were set up under one bough shade. Food was cooked on outside stoves. In the first year, a male and female ablution block, a wash house was built, and a new cement floor for a home for my family was laid.

Originally, my parents had dreams of learning a language to communicate better with Indigenous Australians but were hampered by the workload and the six different languages and little English spoken by the 26 people on the Mission. Also, under WA policy at that time, Aboriginal people were expected to assimilate into British society, live its values and reject those aspects of their culture that were in conflict. This meant giving up their languages, and cultural practices.

My parents were largely ignorant concerning the broader cultural, social, political, and governmental tensions in the Kimberley when they arrived. They were excited about the future, driven by their firm Christian conviction to tell others about the Good News of Jesus and to provide education for the children of the Kimberley.

They learnt to speak Kriol, a language that emerged in Australia for communication between Aboriginal groups and English speakers. By mid 1953 with her first born child, my brother, Joel, in her arms, my mother began planning the first school for the children on the Mission.

Meanwhile, many able-bodied Aboriginal people were being sent to government run pastoral stations such as the nearby Moola Bulla set up expressly for the detention and training of Aboriginal people. By 1953, there were two hundred and sixty Aboriginal people living on Moola Bulla. Most were highly-skilled, but none were getting paid, except in rations.

When Allan Goldman, a private buyer, purchased the property in 1955, he assured the government that he would allow the Aboriginal people to keep living and working there. However, within days of the purchase he made it clear he only wanted to keep a small group of the workers.

Everyone else was asked to leave and he arranged trucks to transport them to Halls Creek. Traumatised, they were unloaded at the racecourse where they camped because they had nowhere else to go. Their displacement to Halls Creek without any shelter, work, or food caused media attention and embarrassment for the Government.

When the call to my father came, late at night, he answered apprehensively. It could only be an emergency this late. The voice on the other end was strained but firm. District Officer Jim Beharell, from the newly formed Department of Native Welfare, advising my father that 150 to 200 people from Moola Bulla station near Halls Creek would be arriving at the mission in the next few days.

Shocked at this news, Bruce stammered: “We don’t have the resources to be able to provide for that many people”.

He was ordered to take them and so put his faith in God.

Six truckloads of people arrived over the next five weeks, on the 1st, 5th, 6th, 8th, and 26th of July and 11th of August 1955, bringing a total of 157 new residents, including 36 girls and 27 boys. Biddy Trust who came from Moola Bulla remembers: “A big truck came, semi-trailers, about five trips, we were loaded up to Fitzroy Crossing and your dad didn’t know what to do with all of us. He was just starting, poor thing. He was only a new missionary starting out , hey.”

Dorothy Lee Tong, who was one of the newly-arrived children, vividly remembers: “That first night your father gave us rice and milk, that was the first time I remember eating rice and milk, that was all they had but it tasted nice with sugar. He said they didn’t have food, but there was more coming.”

My mother wrote home to friends asking for prayer support; she knew that the influx from Moola Bulla had been reported in the papers and supporters may be concerned. She explained that the Moola Bulla people had been turned out of the only home they knew, and that she felt they had to do everything they could to make them as welcome and comfortable as possible, until more resources and help arrived.

It was an emotionally charged time for everyone. They relied on hunting wild game such as kangaroo to supplement their scant food resources. The four missionaries felt the pressure of providing for and settling what was essentially a group of internal refugees.

An elderly lady named Tingle baked bread for the whole Mission. Others erected makeshift homes and tents around the Nissen huts for the families. There were still only a few trees on the Mission due to the drought and rocky ground, and the tents were very hot during the day. Food rations arrived after a few days and were ongoing but basic. A large herd of goats and a flock of chickens were developed to increase the food supply. A few stations kindly provided a whole butchered cow each week.

Over time, my mother would build a school, to educate the children, to teach them to read and write in English, and so to give them a chance in this changing world. Over the next 15 years, most tribal groups in the Kimberley would be forced off their traditional lands. Each displacement was just as devastating, and my parents helped where they could.

I would live among Aboriginal people until age twelve, when I was sent to boarding school in Perth. The culture shock was extreme. Then, as a young woman, I met and married someone on a similar journey to myself, an Aboriginal man from Meekatharra. We lived in Perth; he studied social work and I had our first child. When I was pregnant with our second child, he died in a motor vehicle accident while coming home from work. I was left to raise two children.

Five years on my own with two children was a challenge. Later I married again, this time a pastor’s son and doctor who provided stability and security as I developed my own career. We now have a large and blended family but, as I grew older, I was plagued by many questions, and no one I knew seemed interested in exploring the answers with me, without some tension building. I set out to write this book to honour my parents and to describe my experience.

Extracted from No Turning Back: Life Story of Pearl and Bruce Smoker (Initiate Media) by their daughter Keren Masters, $29.99, available online.

Keren Masters (nee Smoker) and her brothers were raised alongside Aboriginal children on a Christian mission in the Kimberley, Western Australia.

As a child, she learned to speak Kriol - a mix of local Aboriginal languages and English and at age 12, she was sent to an all-white boarding school in Perth, quite the culture shock. The launch of her book was attended by many Indigenous women who remembered her parents.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout