Nicholas Mangan’s new exhibition looks closely at time, money, energy and the possibilities for recycling

Artist Nicholas Mangan’s new exhibition A World Undone at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia explores a time before consciousness and life itself.

The French enlightenment author Bernard de Fontenelle, who himself lived to the impressive age of 100 (1657-1757), told an amusing and discreetly subversive tale about several roses having a philosophical and even theological discussion. The flowers have always been looked after by the same gardener, they have never known any other, and so they speculate that he must be immortal. The decisive argument is that “no rose can remember ever seeing a gardener die”.

This oddly memorable little story poignantly reminds us that our sense of time is proportional to our own life-spans and the consequent pace at which we experience its passage. Insects that live for a few days or weeks seem to us to be constantly in a state of hyperactivity; great trees that endure five or 10 times as long as we do grow so slowly that, although they are in constant movement, we can only perceive it through time-lapse photography. If they were conscious, they would no doubt think of us as scurrying around like busy and restless ants.

Even leaving aside the ultimate metaphysical question of the nature of time – whether it is an intrinsic property of being or merely a structure imposed on reality by human consciousness – we find it hard enough to understand the day-to-day phenomenological experience of duration, let alone the chronology of ages before us. The whole of recorded human history is just a few thousand years old; the first formal histories were written about 2500 years ago, and the earliest inscriptions date back two or three thousand years earlier. Before this, modern homo sapiens had already been living for some 150,000 years in the slow motion of prehistory.

This extraordinary extent of time is itself almost impossible for us to understand in any meaningful way. If we have some conception of the historical era, it is because it is structured by the story of technological advances, the spread of civilisations, the rise and fall of empires. But how are we even to imagine countless millennia in which essentially nothing happened and generation after generation of humans lived in almost exactly the same way as their predecessors? Technological and social change unfolded with glacial slowness.

But even this is nothing compared to the vast extent of biological time, measured in millions rather than thousands of years, or finally of geological time; it is easy to speak of these ages as unimaginable, but that is literally true. We can describe such periods in a theoretical and intellectual way and make graphs and timelines to illustrate them, but we cannot conceive of them with the same resources of the imagination which make it relatively easy, for example, to form a clear idea of the period between Fontenelle’s lifetime and our own day. The capacity for self-awareness of prehistoric humans was very limited, but in these prehuman ages the world existed without any kind of consciousness at all.

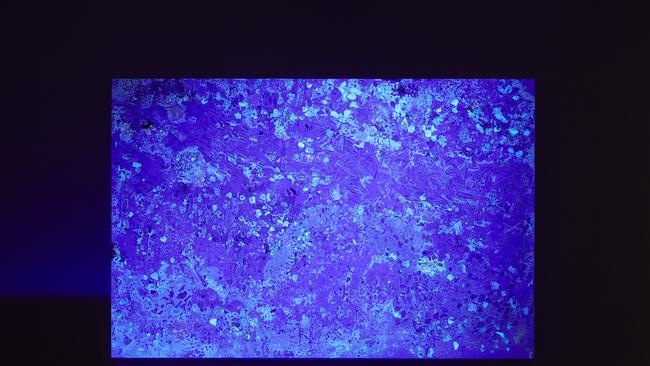

These remotest ages before consciousness and even life itself are at the core of Nicholas Mangan’s inspiration. In the work from which the title of the exhibition is taken, he has crushed zircon found in Western Australia into microscopic fragments, as the label explains, and then used a high-speed camera to photograph these particles falling through space against a black backdrop. The resulting video work is shown in slow motion, so that the particles settle slowly like a cloud of primal matter before the formation of solid bodies.

In a related piece, the particles themselves are shown in a frame between two panes of glass, recalling the sand in an hourglass, as the label once again suggests. The work reminds us that for practical purposes we think of time as a process or cycle of formation and disintegration or entropy; in the world of living things, time measures the alternation of growth and evolution on the one hand, and ageing, death and decay on the other.

Many other images in the exhibition evoke similar cycles, including tree rings that reflect climate conditions during the years of their formation, sun spots, coral structures and termite mounds. All of these images, however, are part of works whose meanings can sometimes be quite recondite; the termite mounds, for example, are produced by 3D printing and are based on networks of underground mines, suggesting an analogy between the activity of termites and those of humans mining the earth for resources.

As this in turn suggests, Mangan is not only concerned with geology but also, and perhaps above all, with the way that geological resources are used by humans to construct or to power our own urban habitats. Thus the first work that we encounter on entering the exhibition is an installation including two coffee tables made of limestone.

These unusual pieces of furniture are explained in the adjacent wall panel – some reading is necessary to grasp the background of Mangan’s work – and refer to the history of the small island of Nauru which enjoyed enormous but ephemeral prosperity in the 20th century from the exploitation of its abundant phosphate resources; a shortsighted approach to this exploitation, however, left the small island’s environment devastated and the economy impoverished.

At the end of the exhibition is another installation that once again refers to the problems that can arise from the extraction and sale of resources formed in the remote darkness of the earth’s past, in this case copper mined on the island of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea. In the 1970s, the Panguna copper mine in Bougainville was apparently the biggest open-cut mine in the world, but there was considerable local opposition.

A revolt was led by the Bougainville Revolutionary Army, and this elicited a response from the PNG government, which sent in troops to suppress the rebellion. The result was a civil war that lasted from 1988 until the Bougainville Peace Agreement of 1998, under which the island was granted regional autonomy. Aspects of life at the mine as well as episodes of the fighting between the opposing forces are recalled in a collage of grainy contemporary documentary footage, while other parts of the installation evoke the way that the islanders, deprived of fuel among other supplies, found a way to make biodiesel from coconuts, which are abundant in the region.

The problems of trying to monetise resources lead Mangan to ponder the relation between resources, energy and currency.

In one part of a film piece already alluded to, a Mexican peso is seen spinning around on its edge, edited so that it appears to spin unendingly. At the same time this whole piece is powered by a system of solar panels and storage batteries specially set up for this purpose at the MCA. The infinitely spinning coin is thus a kind of metaphor of the inexhaustible value produced by harnessing the energy of the sun.

Another work that deals with ideas of value and currency is inspired by the colossal limestone money known as Rai, which are used on the Micronesian island of Yap, part of the Caroline Islands in the western Pacific. These are limestone wheels as big as millstones, with a hole in the centre, presumably to make them easier to transport; but in fact moving these giant tokens of value is impracticable, so a very unusual custom evolved: the ownership of Rai could be transferred from one man to another, without its physical location needing to be changed; and although the islanders had no writing, the oral record and memory of ownership sufficed to make the system work.

This idea of a value that was notional and did not require taking physical possession of the token that represented it struck Mangan as analogous to the way that cryptocurrency works today, and it inspired a work, or rather two, for the second is made with the recycled material of the first.

In the first stage of this project, Mangan set up a bank of bitcoin-mining computers to produce the bitcoin currency. But as bitcoin mining is in fact environmentally very destructive, using vast amounts of electricity as well as water to cool the computers, Mangan sought to mitigate the damage by using solar power to run his computers.

Thus the bank of computers at Monash University in Melbourne worked day and night “mining” bitcoin, and the value generated by this activity was used to fund the other part of the project, which was set up in Berlin. Here an industrial printer would endlessly roll out reproductions of what appears to be a late 19th century photograph of a series of rai on the deck of a sailing ship.

All of this is explained in a couple of videos, shown on alternating screens, that also include historical documents and photographs and even cartoons in which the giant stone tokens appear. The coincidental similarity in form of the rai token and the logo of Macquarie Bank is alluded to as well; as readers no doubt know, Governor Macquarie, faced with a chronic shortage of currency in the early colony, received a large shipment of Spanish dollars from the British government, punched out their centres and counter-stamped them, thus destroying their original value as Spanish money but creating two new coins for the colony, the so-called “holey dollar” and the “dump”.

At the conclusion of this work, Mangan brought back large rolls of the photographs from Berlin and set about creating a second work which would essentially recycle the first one. All the computers used in the original bitcoin mining array were dismantled and their metallic parts extracted. The aluminium from the computer bodies was melted down and turned into stacks of ingots.

The photographs were even more ingeniously recycled, first shredded and then turned into a papier-maché mixture from which the artist formed a huge reproduction of a rai, which leans up against a wall in the exhibition. It is curious how differently we see this object when we realise how it has been made and that it is of course much lighter than it would be if carved out of solid limestone.

It’s unclear what exactly we have learnt about currency and the production of value through the cycle of these two works, intriguing as they are in themselves. Does the bitcoin mining experience suggest that such currency is grounded in some objective resource value, or the “use-value” of a resource, rather than being simply a symbolic measure of value?

Or is bitcoin itself simply a colossally expensive and wasteful way to produce a form of currency, which seems in some respects to contradict the radically abstract conception of money implied by blockchain technology?

At any rate, Mangan has at least fully recycled all the materials involved in this project, thus achieving something like – at the risk of a pun that is virtually unavoidable in the circumstances – a circular economy.

Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone

MCA to June 30

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout